On August 2, 2021, the Israeli Supreme Court conducted a hearing on the appeal of four Palestinian families against lower court verdicts allowing a corporation associated with the East Jerusalem settlers to evict them of their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem. The hearing was an important milestone in an ongoing and unfolding saga that will possibly lead to the displacement of Palestinians in four targeted areas in East Jerusalem. The growing possibility of evictions in Sheikh Jarrah has stirred controversy for years. However, in recent months, as the prospect of the evictions loomed ever larger, these potential evictions has generated wide media coverage and a wave of support for the residents in the international community. The rising tension has already triggered intercommunal skirmishing on the streets of Jerusalem and a round of convulsive violence in and from Gaza.

The results of the August 2 hearing were not only inconclusive, but also have given rise to a number of possible interpretations. Having studied the court record, we have concluded that the hearing was a watershed event that, while solving nothing and eliminating no danger, illuminated the current state of play, while creating new rules of engagement among the protagonists, and new, albeit problematic, opportunities.

Below is our analysis of the state of play regarding the Sheikh Jarrah evictions in the wake of the Supreme Court hearing.

In order to simplify matters for the reader, the analysis is comprised of six sub-sections, each of which may be read more or less independently of the other subsections, as follows:

Section 4: The Stakeholders and their Respective Positions

Section 5: The Court Proceedings and the Fate of Sheikh Jarrah

Those who have read our prior reports or are familiar with the background of Sheikh Jarrah and its current geopolitical context can go straight to Section 5.

For a more thorough examination of the background to the events in Sheikh Jarrah, see our recent report, “Large-Scale Displacement: from Silwan to Sheikh Jarrah”. Those interested only in the court hearing and its implications may proceed directly to Section 5.

Section 1: Executive Summary

- While the Supreme Court is pushing the parties to reach a settlement agreement, it currently appears less rather than more likely that they will succeed.

- The proposed settlement agreement, still open to negotiations, gives the Palestinian residents some benefits, while entailing both risks and painful concessions: they will likely (but not certainly) be able to remain in their homes for decades as protected tenants, but they will need to waive most (but not all) of their claims of ownership. While the risk of eviction is significantly lower, their rights to remain for decades are not entirely iron-clad, and the risk will not disappear.

- In the absence of a settlement agreement, the Supreme Court will inevitably hand down is verdict in the weeks or months to come.

- The Court left little doubt that prior court verdicts (res judicata) create a virtually insurmountable barrier that will likely prevent the residents from having their motion heard on its merits.

- Failing a settlement agreement, a Supreme Court ruling against the residents is much more likely.

- If there will indeed be a verdict against the residents, it will not likely be implemented in the coming months, perhaps longer. However, once such a verdict exists, the actual eviction is virtually inevitable, in a matter of years at the most.

- A verdict in favor of the settlers will likely serve as a precedent for the other cases in Shimon Ha-tzadik, but not for the eviction proceedings in Um Haroun and Batan al Hawa/Silwan.

- The grassroots protests and the international engagement on Sheikh Jarrah have had a highly positive impact to date and are absolutely essential in maintaining the possibility of even a partially satisfactory outcome.

- It is not too soon to prepare for the consequences of a Court ruling against the residents. Such a verdict itself may suffice in causing an eruption of violence, even before any evictions take place.

- Even if there will be a court verdict in favor of the settlers, there still will be the possibility, however remote, of preventing the evictions. These possibilities need to be explored even now.

Section 2: The Background

Sheikh Jarrah is a largely upscale Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem which developed as Jerusalem grew beyond the walls of the Old City.

- Historical background

- The 19th Century –In 1876, two Jewish religious associations, the Sephardic Community Council and the General Council of the Congregation of Israel reportedly purchased rights to an ancient burial grotto, the Tomb of Shimon Ha-tzadik (“Simon the Righteous”), and to an additional 17.5 dunams (about 4.4 acres) adjacent to it. A small complex of buildings was built on part of the plot, housing approximately 50 Jewish residents, while most of the site remained empty. In 1948, with the outbreak of the hostilities that also engulfed Jerusalem, the residents of Shimon Ha-tzadik were evacuated upon instructions from both the Hagana (the Yishuv’s pre-state para-military organization that operated in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and 1948), and the British Mandate authorities.

- 1948-1967 – In the aftermath of the 1948 war, Sheikh Jarrah became part of Jordanian East Jerusalem. In 1955, in a cooperative endeavor of UNWRA and the Government of Jordan, homes for 28 Palestinian refugee families were built on the site. Paying nominal rental payments, these families concluded long-term lease agreements with Jordan, three years in duration, with a mechanism that was ultimately to lead to their full ownership of the property. The four homes that are the subject of the current court proceedings are among those 28 homes.

- Post-1967 – In the wake of the 1967 war, the two Jewish associations that had acquired rights to the Shimon Ha-tzadik compound took legal action against the Palestinian residents, invoking Israeli legislation enacted in 1970 that empowered those who lost property in East Jerusalem in the 1948 War to recover that property. As we shall see, the ability to recover property lost in the 1948 war was limited to East Jerusalem, and does not apply to Palestinian properties lost in West Jerusalem as a result of the 1948 war. Consequently, Jews can recover property lost in the war, while Palestinians cannot.

- The 1982 agreement – In 1982, there was an agreement between the residents and the Jewish associations that was validated by a court verdict, whereby the ownership rights of the religious associations were acknowledged, and the Palestinian residents of these homes were recognized as protected tenants. The Palestinians of Sheikh Jarrah vehemently contest the validity of that settlement agreement.

- The 2003 purchase by the settlers. In 2003, a company incorporated in the United States, Nahlat Shimon Ltd. which is associated with the Israeli settlers in East Jerusalem (hereinafter: “the settler company” or “the settlers”), purchased the rights of the two Jewish associations in Shimon Ha- tzadik. Between 1988 and 2017, the associations and the settlers succeeded in evicting seven of the Palestinian families in Shimon Ha-tzadik, in legal action based on claims of purported violations of protected tenancy laws.

- The pending eviction proceedings, 2009 – 2021 – At the end of the first decade of the 21st century, the settlers began to systematically institute eviction proceedings against Palestinian residents in Sheikh Jarrah, again claiming that the residents had violated the tenancy laws. There are fourteen buildings currently subject to pending eviction proceedings, and are the very same houses built by the UN and Jordan in the 1950s. These include the four families that are the subject of the current Supreme Court case.

- The current Supreme Court case, 2021. The eviction proceedings against the four Palestinian families whose cases are currently before the Supreme Court were instituted in 2009 and 2010. In 2020, the Jerusalem Magistrates Court ruled in favor of the settlers, enabling them to evict the families forthwith, and in February 2021 the Jerusalem District Court upheld the verdict of the lower court. The Palestinian residents have now moved that the Supreme Court grant them leave to appeal the verdicts of the two lower courts. Formally, the question before the Supreme Court is whether to grant the residents leave for a second appeal. Only if the right to appeal is granted will the Court hear the substantive claims of the parties.

- The geopolitical context

Settlement activity in Jerusalem’s Old City and its environs has always generated controversy. However, the proposed evictions have characteristics not witnessed in the past:

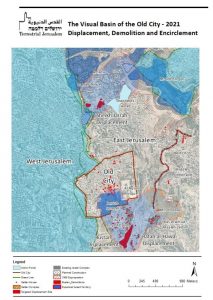

- Unprecedented large-scale displacement. Since 1967, Israel has populated the large settlement neighborhoods of East Jerusalem with 225,000 Israelis, without engaging in the large-scale displacement of Palestinians. The last and only large-scale displacement in East Jerusalem took place on June 10, 1967, with the razing of the Mughrabi Quarter in the Old City

. Israel’s actions threatening to displace the Palestinian residents of four neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, two in Silwan and two in Sheikh Jarrah, is unprecedented, unlike anything Israel has dared to carry out since 1967.

. Israel’s actions threatening to displace the Palestinian residents of four neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, two in Silwan and two in Sheikh Jarrah, is unprecedented, unlike anything Israel has dared to carry out since 1967.

- The territorial dimension. The planned settlement in Shimon Ha-tzadik is not taking place in isolation. It is just one of a series of projects, largely governmental, geared to encircle the Old City with biblically themed and inspired settlements and parks. The projects in Sheikh Jarrah ring the Old City on the north, and the Silwan settlements and parks encircle it on the south and east. This has far-reaching ramifications for any future political agreement regarding the status of Jerusalem.

- The religious radicalization of the conflict. The creation of a biblically motivated settlement in Shimon Ha-tzadik is part of a broader trend in Jerusalem: the ascendancy of religious factions – Jewish, Christian and Muslim – which weaponize faith. Their claims to the city are exclusive, absolute, exclusionary and often incendiary, and contain the seeds of a transformation of an ultimately resolvable national-political conflict into a zero-sum religious conflict.

- The Naqba dimension. . The recent violent events of May 2021 has demonstrated that the prospect of largescale displacement of Palestinians by Israelis in the heart of Jerusalem is not a local event. It evokes among Palestinians the traumatic memories of the Naqba and as such resonates well beyond the boundaries of Sheikh Jarrah. It sent shockwaves not only throughout the West Bank, Gaza and the Arab world, but also gripped the Palestinians citizens of pre-1967 Israel as well.

- Sheikh Jarrah as detonator. There are two components of the Israel-Palestine conflict which touch on the core of the national identities of Israelis and Palestinians: Jerusalem and the fear of displacement. Reckless acts regarding each of these invariably entail serious potential for an eruption of convulsive violence. The evictions in Sheikh Jarrah fuse these two “radioactive” elements of the conflict, Jerusalem and displacement, making the situation in Jerusalem exponentially more volatile.

- Israel’s international standing. Consequently, it should come has no surprise that the prospect of evictions in Sheikh Jarrah has generated concern and interest throughout the world – in public opinion and in the corridors of power – of a scope and intensity not witnessed in recent memory. These events are already taking their toll in the support for Israel, even among its traditional allies.

Section 3: East Jerusalem Sheikh Jarrah and the Law

Official Israel’s position on the legal and political status of East Jerusalem is at loggerheads with the provisions of international law as seen by a large majority of the rest of the world.

1. The position of the international community

It is almost universally accepted that under international law, the status of East Jerusalem is no different than that of the West Bank: it is occupied territory, under belligerent occupation as determined by international law. Consequently, Israel’s 1967 annexation of East Jerusalem is illegal.

In the context of Sheikh Jarrah, this inevitably leads to the following conclusions:

- The forceful displacement of Palestinians in East Jerusalem, as well as the transfer of Israeli population to settlements is a violation of international law, and potentially a war crime.

- In East Jerusalem, it is international, not Israeli law that applies, and the Israeli courts have no jurisdiction.

- Israeli legislation and Israeli policies regarding Sheikh Jarrah are not only grave violations of international law. The fact that it applies differently to the two national collectives in the city has stoked the accusations of apartheid against Israel.

2. Israel’s official position towards East Jerusalem

From an Israeli perspective, East Jerusalem is an integral part of Israel, no different from Tel Aviv or Netanya in its political status. Accordingly:

- East Jerusalem is governed by Israeli law. International law does not apply and is, at best, something that may occasionally influence the ways in which the courts interpret Israeli law.

- The Israeli courts are the exclusively competent court of record in East Jerusalem.

- The Knesset is sovereign, and its legislation, including that regarding property lost in East Jerusalem, is valid and binding.

- In spite of their status as permanent residents, and not citizens, the Palestinians of East Jerusalem enjoy equality before the law. The situation in Sheikh Jarrah does not change that. Charges of apartheid are baseless.

- The matters of Sheikh Jarrah are internal, domestic Israeli issues, in which the international community has no role to play.

- The Israeli Courts and East Jerusalem

- The inherent divide between the judiciary and the Palestinians of East Jerusalem – The civil and criminal affairs of the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem come before Israeli courts and are adjudicated by Israeli judges. These judges include a number of Palestinian citizens of Israel, but since the Palestinians of East Jerusalem are not citizens, they may not ascend to the bench. The separate lives and lifestyles of Israelis and Palestinians in Jerusalem make most of the Israeli judges largely unfamiliar with the conditions of life in East Jerusalem.

- An organ of state for conflict-related issues – Courts of law are by their very nature janus-faced institutions. On the one hand, they are mechanisms for the administration of justice, and on the other hand, organs of state. In situations of national conflict, the courts tend to act as organs of the state (and Israel is not unique in this regard), while in more mundane affairs, the rulings tend more to administer justice in according to the evidence at hand. Just as the US Supreme Court refused to rule on the legality of the Vietnam war, Israeli courts have been highly reluctant to deal with issues entailing manifestations of Israeli occupation: i.e. the legality of settlement activity, home demolitions, revocation of residency rights etc. In private civil disputes not directly related to the conflict, the Palestinians of East Jerusalem may reasonably expect to have their day in court; in conflict-related issues they may well receive “tea and sympathy”, but rarely judicial relief.

- The perceived inapplicability of international law – Israeli courts will invariably rule in matters relating to East Jerusalem based on Israeli law, never on the basis of international law. Were an Israeli judge to view East Jerusalem as occupied territory, he or she would have only two options: to leave one’s views at home, or to leave the bench. Ruling on the basis of international law is unthinkable.

- Sporadic attempts to mitigate the impact of the occupation – Increasingly, a number of judges have disclosed an awareness that some of their rulings are based on convenient fictions that are essential to the claims of the legitimacy of Israeli rule in East Jerusalem. In recent years, there have been a number of cases in which the courts have “pushed the envelope”, interpreting the law in ways that mitigate some of the most blatant effects of occupation, without acknowledging that occupation exists.

Israeli legislation, like the Absentee Properties Law, often poses a grave threat to the property rights of the Palestinians of East Jerusalem. The laws applying to residency create circumstances whereby the right of a Palestinian to remain in the city of his or her birth, and where his family has lived for centuries, can at times be revoked. Some judges have felt compelled to acknowledge, at least implicitly, that these laws are built on the fictions of an undivided Israeli Jerusalem, and that a faithful application of the letter of the law can have a devastating impact on the fundamental rights of the Palestinians. In recent years, the Israeli Supreme Court has ruled that the property and residency rights of the Palestinians must be better secured, and may be curtailed or revoked only under the most extraordinary of circumstances.

These examples are rare and limited in scope. They require courageous jurisprudence, which by its very nature tends to be reserved to the Supreme Court. Even then, these rare rulings are handed down only under exceptional conditions. Neither the provisions of international law nor an explicit recognition of occupation ever get past the front door of the courtroom.

These dynamics are very much in play in the deliberations on Shimon Ha-tzadik that are taking place before the Israeli Supreme Court.

Section 4: Sheikh Jarrah: the Stakeholders and their Respective Positions

There are a number of protagonists in the drama unfolding in and regarding Sheikh Jarrah.

- The Palestinians residents

- The four concerned families – The four families who are appealing the judgments that allow for their eviction live in four of the 28 homes built by the UN and Jordan in the mid-1950s. These are the 1948 refugees for whom the homes were built, their immediate successors, or, in one case, a family member who acquired rights from the original residents.

- Pending eviction proceedings in Shimon Ha-tzadik – Of the 28 refugee families in Shimon Ha-tzadik, seven have already been evicted on a one-by-one basis in legal proceedings that took place between 1988 and 2007. Eviction proceedings are currently pending against another 14 families in Shimon Ha-tzadik. Consequently, we are dealing with the large-scale displacement of an entire neighborhood – 21 out of 28 families.

- Palestinian communities under threat of eviction in East Jerusalem – As noted, the events in Shimon Ha-atzadik are not taking place in isolation. There have been eviction proceedings instituted by the Israeli Government, or settlers acting hand in glove with Government, against approximately 160 Palestinian families in East Jerusalem. Approximately 60 of these families are in two areas of Sheikh Jarrah and about another 100 households in Batan al Hawa in Silwan. Shimon Ha-tzadik is one of these targeted areas. The evictions are being complemented by other settlement-related government projects, such as the construction of parks, roads, public buildings etc. which are transforming Sheikh Jarrah from a discontiguous settlement enclave into an extension of pre-1967 Israel. In addition, looming on the horizon is the possible demolition of approximately 78 buildings with 130 households in the Al Bustan area of Silwan.

- The “Hebronization” of Sheikh Jarrah – The refugee families of Shimon Ha-tzatzadik have already been schooled in crushing adversity. They have been subject to several rounds of eviction proceedings dating as far back as the 1970s. They have seen some of their neighbors evicted, and several are sharing the buildings with hostile settlers. Still, as tense as intercommunal relations may be, Jerusalem has never possessed the intensity and the toxicity that characterize the relations between Jews and Arabs in Hebron. However, in recent years, settlement activity is “Hebronizing” Sheikh Jarrah.

- Sheikh Jarrah as a Palestinian national symbol. In recent years, Sheikh Jarrah has become a leading focal point of Palestinian resistance to occupation. There has been a groundswell of support for the residents of Shimon Ha-tzadik, domestically and internationally, unprecedented in scope and appeal. Their neighborhood has been the focus of protests by Palestinian, Israeli and international activists, and is frequented by foreign diplomats of concerned countries. The settlers and the extreme right have targeted the area for provocative demonstrations. For months, the residents of Shimon Ha-tzadik have been under a sporadic siege by the Israeli police, who restrict the movements of the residents and the press, while allowing free movement to the settlers and their supporters. Gratuitous police violence is commonplace.

These refugee families have consequently found themselves, through no fault of their own and having no choice in the matter, as lead protagonists in one of the epicenters of contemporary history. As we shall see, the symbolic role assumed by and imposed on the residents is already having an impact on the court proceedings.

- Nahlat Shimon Ltd.

We know precious little about the settler-owned/controlled company that is the purported owner of the Shimon Ha-tzadik site, and which is seeking to evict its Palestinian residents. That in itself is perplexing. We have been witnessing settlement activities within the existing Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem since the 1980s. There is a small, well-known and very powerful cluster of settler organizations who focus their activities in those areas which they perceive as resonating with Biblical history: the Muslim and Christian Quarters of the Old City, Wadi Hilweh/Ir David and Batan al Hawa/the Yemenite Quarter in Silwan, Beit Orot and Ma’aleh Zeitim on the Mount of Olives, and the Um Haroun/Georgi Jewish neighborhood and Shimon Ha-tzatzadik in Sheikh Jarrah. These organizations have divided the turf in which they are active among themselves: Elad focuses on the City of David and the Mount of Olives, Ateret Cohanim is active in the Old City, Kidmat Tziyon and Batan al Hawa, and the compounds in Ras al Amud/Ma’aleh Zeitim and Shepherds Hotel are associated with the late settler patron, Dr. Irving Moskowitz.

While there are some ideological nuances among these organizations, they share the goal of establishing some sort of renewed Biblical realm around the Old City and the Temple Mount, by means of Jewish settlement. While their operations are often cloaked in secrecy, their identities, mode of operations and motivations are well-known.

That is not the case with Nahlat Shimon Ltd. Recent reports by investigative journalist Uri Blau have revealed that Nahlat Shimon is the last in a chain of shell companies registered in different countries, the owners and directors of which remain anonymous. Aside from their US attorney, the only individual known as being associated with the Nahlat Shimon Ltd. is a settler activist, Tzachi Mamo. Mamo has been long engaged in settlement activities in East Jerusalem and the West Bank, using front companies to acquire properties from Palestinians for the purposes of Jewish settlement. He has generally kept a low profile, so far deflecting periodic police investigations for fraud.

There is little doubt as to Mamo’s ideological affinities. Journalist Uri Blau revealed the way the Rabbinic Courts have described Mamo’s endeavors in in Sheikh Jarrah:

“Tzachi Mamo did holy work… We’re confident had it not been for vigorous actions [by Mamo and his colleagues] to redeem Jewish properties in the area of old Jerusalem and to have them settled by Jewish families that live there devotedly, many buildings would have remained under gentile possession, and entire neighborhoods would have remained ‘purged’ of Jews.”

Mamo himself has stated: “My job varies from company to company and mainly includes work in the sphere of buying the properties and evicting…[ the Arab residents]”.

While that may suffice in identifying Nahlat Shimon’s ideological affinities, it leaves us in the dark as to their specific objectives, and how these relate to the court proceedings. Who is behind the company, and who funds it? All we know is that it was incorporated in 2000 in Delaware, and in 2003 purchased the rights in Shimon Ha-tzadik from the Jewish associations for $3,000,000. What are their plans for the site, and what is their time-line? Who makes the decisions? What do they expect from the current court proceedings? We don’t know.

We will examine the company’s legal claims in Section 5 below.

- The international community

As noted, there has been a groundswell of support for the residents of Sheikh Jarrah. Sheikh Jarrah has become in many places a household word, and has assumed a prominent place in the media around the world. This is likely the result of grassroots efforts and sustained behind-the-scenes diplomatic efforts that have been discreetly pursued for several years.

As the court proceedings brought the prospect of evictions ever closer, this public campaign spread from Jerusalem to North America and Europe. Initially a campaign led by Palestinian and pro-Palestinian activists, it quickly garnished the support of people not customarily involved in Israel-Palestine issues. Prominent political leaders abroad who were customarily supportive of Israel have expressed harsh criticism and deep concern over the matter, both publicly and behind closed doors. The periodic visits to Sheikh Jarrah by members of the diplomatic community in Jerusalem (Consuls General, State Representatives and their staffs) synergistically amplified the impact of both the public campaign and the discreet international engagement. Sheikh Jarrah has become an issue that cannot be ignored nor easily dismissed.

Regardless of what the final result may be, the international engagement has already had a significant impact. Until recently, the Israeli Government which has been deeply involved in the settlement schemes showed no interest in the Sheikh Jarrah evictions. Today, the Government, up to and including the Prime Minister, is deeply troubled by the possible diplomatic ramifications of the evictions in Sheikh Jarrah.

- The Government of Israel

- A government-settler joint venture – For decades, the settlement activities in Sheikh Jarrah have enjoyed massive and well-funded support in the framework of a flagship, multi-year government project initiated by Ariel Sharon in 2005. Without this systematic and large-scale support of the Government and the Jerusalem municipality – from partisan policing and government funded private security, to the creation of infrastructures geared to serve the settlements etc. – it is unlikely that these settlements could have been created or sustained.

As the decisive Supreme Court hearings approached, Israel attempted to downplay the significance of Sheikh Jarrah, asserting that “ … the PA and Palestinian terror groups are presenting a real-estate dispute between private parties, as a nationalistic cause, in order to incite violence in Jerusalem“. However, by the time the Ministry of Foreign Affairs made that statement, very different views of Sheikh Jarrah had already crystallized in other quarters: internationally, Sheikh Jarrah is now widely seen as a major, dangerous and non-routine clash, a potentially pivotal development with far-reaching ramifications. Israel’s attempt to dissociate itself from the evictions is often viewed as disingenuous in the extreme, and a thinly-veiled attempt to implement governmental settlement policies by proxy.

- The sole direct intervention of the Israeli Government – On one occasion, developments on the ground compelled the Government to intervene openly. The Supreme Court hearing on Sheikh Jarrah was originally scheduled for May 10, 2021, coincidentally falling on Jerusalem Day, when the settler right and its supporters customarily march through the Old City in their controversial and inflammatory “Dance of the Flags”. Since Ramadan had been celebrated days before, Jerusalem had already been witnessing clashes on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif and at Damascus Gate. In Sheikh Jarrah, the numbers of protestors swelled, and there were clashes between the residents on the one hand, and the settlers and police on the other. Sheikh Jarrah was looming large, and the potential of an outbreak of violence was both palpable and widely discussed.

On May 9, a day before the scheduled hearing, the Attorney General, acting under instructions from the Government, filed a motion to the Court, requesting for a deferral to respond to the Palestinian residents’ request that he would become a party to the case. The main reason given was that the Attorney General needed time to consider joining the proceedings under the provisions of Section 1 of the Procedure Ordinance (The Appearance of the Attorney General) [New Version], which states:

“…should the Attorney General determine that any right of the State of Israel or the rights of the public or the public interest be influenced or tied, or may be influenced or tied, to any matter before the Court…he is entitled to appear in that proceeding and to state his position”.

The Court accepted the motion and rescheduled the hearing for August 2. But this intervention was “too little, too late”. With tensions running high, the “March of the Flags” to Damascus Gate led to clashes with the police, which in turn triggered the violence between Israel and Gaza, with rockets fired into Israel and Israeli bombing of highly populated areas in Gaza ensuing.

In his submission to the Court, the Attorney General did not explicitly address the issue of potential violence, but instead alluded to it, almost “in code”:

“This proceeding entails sensitivities in other matters, and the Attorney General moves, ex parti, to submit to the Court the expert opinions of diplomatic authorities and other relevant parties in government. In light of the urgency of these materials they are being attached in a sealed envelope”.

- The government’s attempt to distance itself from the case – Ultimately, the Attorney General elected not to join the proceedings, nor has he joined any of the other eviction proceedings regarding East Jerusalem. With rare exception (such as the Foreign Ministry’s “real estate dispute” gaffe), no one in the Israeli government has spoken out publicly or taken any action on Sheikh Jarrah.

This passivity is somewhat perplexing, and Israeli governments have acted differently under similar circumstances in the past. In 1997, settlers attempted to move into homes they had purchased in Ras al Amud. Prime Minister Netanyahu balked at allowing them to move in, and instructed the Attorney General to rule on the PM’s authority to prevent occupancy by the settlers. Attorney General Elyakim Rubinstein held that in cases of “near certainty of public disorder and endangerment of public safety, it is permissible to prevent tenants’ moving into a residence even if it was legally purchased.” Prime Minister Netanyahu himself told Israel Broadcast News that “…[the] entry of Jewish families into Ras al-Amud is bad for Jerusalem and bad for the State of Israel” and that “…while the families legally entered property owned by Jews, only the government will decide on settlement in sensitive areas.”

In contrast, the current Government is treating Sheikh Jarrah as one would treat a dark family secret: everyone knows how sensitive and dangerous the matter is, but no one dares talking about it. Fully aware of the implications of Sheikh Jarrah and deeply concerned, Prime Minister Bennett and his cabinet have not dared speak out, much less act, on the potential evictions. From their perspective, Sheikh Jarrah is apparently too “radioactive” an issue for this fragile coalition to take on.

Virtually everyone in official Israel wants the matter of Sheikh Jarrah to simply “go away”, but everyone also expects another branch of government to do the “dirty work”. The judiciary wants the government to take action, the cabinet hopes the courts will defuse the issue, and everyone wants the Attorney General to act on the matter with courage he has never displayed in the past. That is the context in which the Supreme Court is conducting the deliberations.

Section 5: The August 2 Court Proceedings and the Fate of Sheikh Jarrah

On August 2, the Supreme Court heard the motion to grant the residents the right to appeal the judgments of the lower courts. While the two prior hearings were held before a sole Supreme Court justice, this hearing was before a panel of three.

We wish to highlight what transpired in the hearing, and what, if anything can possibly be learned from it.

- Choreographing the neutralization of conflict

An innocent observer of the deliberations would have had no idea that the hearing dealt with the bitter, emotion-charged controversy of epic proportions that was raging outside the courtroom. There were no mentions of “settlers”, “Jews”, “Israelis”, “Palestinians” or “Arabs”. There was no occupation, no large-scale displacement, no mention of international law, no laws discriminating between Israelis and Palestinians, no government-sponsored settlement enterprise in and around the Old City, etc. It was only the presence of large numbers of diplomats and press that indicated that this was no routine matter.

However, even with no mention, these issues hung over the deliberations like a pall. Everybody in that courtroom knew what was happening, but no one dared mention it, except by means of a rare innuendo.

This was to be expected. The Israeli courts do not recognize the jurisdiction of international law in East Jerusalem and work diligently in preventing politics, ideology and passion from seeping into the court room, embroiling the Court in controversy. The parties will generally avoid the risk of angering the Court by breaking their ground-rules.

In the hearing, the Court actively sought to neutralize the effects of the notoriety of Sheikh Jarrah, the influence of press coverage, and the impact of history, recent and ancient, that have turned it into such a powerful symbol.

When counsel for the residents asked for a half hour break in the deliberations, Justice Amit quipped, half-facetiously: “When we go out for five minutes, we know what happens. The press pounces, and everyone takes this and that kind of advice. If we take a break the doors will be closed. You are under arrest here, in case you didn’t know” (CR, p. 12). Justice Amit concluded the proceedings by saying that “…the next time we meet, we ask that there be less people here. All the parties know exactly what I am talking about” (CR, p. 29).

From the Court’s perspective, the press, history, memory, ideology, and the quest for absolute justice and victory apparently stand in the way of reaching such an agreement. For example:

- Justice Barak-Erez: “The honorable counsel for the plaintiffs] is piling on history. They also have history (CR, p. 9.

- Justice Amit: “We are trying to reach a pragmatic agreement, without declarations of this and that kind of ‘victories’, and we have seen how much this interests the press. We’re not in the game. We want a practical solution… (CR, p.4)]… Everyone wants to ‘push’ his own ideology, and we’re interested in the practicalities” (CR, p.10)].

The Court was likely indicating that they believed that the interests of justice would be best served not by a verdict with potentially dangerous consequences, but by means of an agreed settlement. However, whatever the Court’s intent, from the Palestinian perspective the Court was dismissive of their past, of their historical claims and their demands for justice for themselves and to the people to whom they belong, reducing them to parties to a technical dispute that can be technically resolved.

2, The Legal Arguments

- The lower court’s ruling. The lower courts had ruled that the settler corporation is the rightful owner of the property in question. This determination was made in large part on a number of previous court rulings, most prominently the 1982 settlement agreement, in which the previous Jewish owners recognized the residents as protected tenants, and the residents recognized (or so it is claimed) the ownership of the Jewish associations. The lower courts further ruled that the residents had violated the laws of protected tenancy, largely by failing to pay the nominal rent payments, a violation that constitutes sufficient cause under law to evict the residents.

2. The settlers’ claims. These court rulings basically accepted the substantive claims of the settler company, which may be summarized as follows:

- The settler corporation has unfettered title to the Shimon Ha-tzadik site, and there is no serious dispute over the ownership of the property, nor its precise location.

- The Palestinian residents have no claims to the property, beyond their status as protected tenants.

- The Palestinian residents are serial violators of the protected tenancy laws. They have systematically violated court rulings and reneged on their obligations under protected tenancy laws. They have not paid the nominal rent for the properties for over a decade. Some have illegally built on the property without the owner’s consent, and some of those living in the homes have taken possession in violation of protected tenancy laws.

- The Palestinians have been attempting to relitigate this case for decades, and to renege on their undertakings under the 1982 settlement agreement.

- The settler company is in principle willing to refrain from evictions, provided that the residents reaffirm the 1982 settlement agreement, and abide by it.

- While the company has in the past disclosed its intention to raze the 28 homes in Shimon Ha-tzadik and to build a settler complex instead, there was no mention of this in the hearing. (As we shall see below, this issue alone might scuttle any possibility of agreement).

3. The Palestinian residents’ claims. The daunting challenge for the residents was to convince the Courts that there was sufficient cause for the Supreme Court to hear their appeal. To do so, they need to demonstrate that they have new and potentially decisive evidence that was not available to them at the time of the original rulings, and that there are important legal issues and public interest at play which transcend the immediate interests of the direct parties to this motion.

These are the major substantive legal claims made by the Palestinian residents:

- There is even no direct evidence of the sale of the property to the Jewish communal associations in 1876, or at any other time. Consequently, there is nothing to support the claim that the Jewish associations had acquired legal ownership of the property. The association could not possibly sell the property to the settlers because they never owned it in the first place.

- The purported settlement agreement of 1982 was concluded by means of the Israeli attorney representing the Palestinian residents – and this was done without their knowledge and consent. It does not bind the residents.

- Nowhere has the precise location of the property purportedly owned by the settlers been conclusively identified.

- When the Jewish associations initiated the registration of the property initiated in 1972, they did so behind the backs of the residents. The claim of ownership itself is tainted with fraud.

- Nowhere have the residents formally recognized the ownership by the settlers, even in the settlement agreement of 1982.

- The Jordanian Custodian for Enemy property acquired legal title to the property, which, based on newly discovered documents in Amman, was about to be transferred to the Palestinian residents immediately before the 1967 war. The fact that the registration of the property in the residents’ name was not formally completed does not derogate from the validity of their ownership. Consequently, it is the Palestinian residents, not the settlers, who are rightful owners of the properties.

- Even if the residents are indeed “protected tenants”, their failure to pay rent is in no way a violation of tenancy laws: the settlers are not the owners (or their “ownership “is very much in doubt) and are not entitled to receive rental payments.

4. The challenges raised by the bench towards the residents‘ claims. The Court largely focused on what they view as possibly insurmountable obstacles that will make it difficult, if not impossible, to accept the motion, and to deal with the residents’ substantive claims:

- Res judicata (For a definition of the term see the following: “Generally, res judicata is the principle that a cause of action may not be relitigated once it has been judged on the merits. ‘Finality’ is the term which refers to when a court renders a final judgment on the merits”). The Court repeatedly suggested that the dispute between the parties had already been settled in the past by a number of competent courts of law: – Justice Amit: “There is no question that the appellants [the residents] have the status of protected tenant, and that’s been determined in perhaps eighteen judgments in the past (CR, p.1); Justice Barak-Erez: “[The honorable counsel for the appellants] has not responded [to the Court’s remarks] that you may not raise some of these matters because of res judicata. Even in the expert opinion you filed, there is no mention of res judicata. You are asking us to ignore the judgment of [Supreme Court Justice Landau] in 1981” )CR, 15).

- Statute of limitations. As noted, the residents claim that the initial registration of the property in the names of the Jewish endowments from whom the settlers purportedly purchased the land in 1972 was fraudulent. The Court challenged the counsel for the residents on this matter. Justice Amit: “All of the arguments you are making so enthusiastically that the 1972 registration is fraud, is in my opinion barred by the statute of limitations… all of this could have been raised in [the Supreme Court proceedings] in 1981 (CR, p. 18) …any judge will toss you down the stairs on the issue of statute of limitations alone” (CR, p. 12).

- A “civil retrial”. The Court asserted that the appeal was an attempt by the residents to get a “civil retrial”, a legal action generally associated with criminal, not civil proceedings. Justice Amit: “[Honorable counsel for the residents] is purporting to claim what we call ‘a civil retrial’…[the 1981 verdict] is not invalid, and at the very most was obtained fraudulently, and you have to file a motion for a civil retrial” (CR, p.19).

- The residents are taking a big risk. While the Court was not dismissive of the claims made by the residents, they made very clear that they had doubts so serious that it would be very difficult, if not impossible, for the Court to accept the motion. Justice Barak-Erez: “[The honorable counsel for the residents] has to demonstrate to us a principle in Israeli law that enables us, this Court, to reopen a court verdict decades later. We are attentive to your claims, but they have to fall within the confines of the doctrine of finality” (CR p. 18). Justice Amit: “Adv. Ersheid, you are encouraging us to rule here and now that this is a case of res judicata (CR p. 9)…is this a risk [the honorable counsel] is willing to take” (CR, p. 14)?

5. The challenges raised by the bench towards the settlers’ claims. The Court also had pointed questions for the settlers:

- Jordan granted or was about to grant ownership to the residents. As noted, in recent months the residents discovered hitherto unknown documents in Amman, showing that immediately before the 1967 war, the Jordanian government was about to register title in the names of the residents. The Court pressed the counsel for the settlers on this. Justice Barak-Erez: “Even if we have dwelled on sundry difficulties encountered by the appellants, there remains the fact that they had an agreement with the Government of Jordan…are you saying that the 28 homes that were built are or are not related [to the agreement]” (CR p. 23).

- The ownership of the property remains undetermined. The Court raised the possibility that while the previous court verdicts unequivocally determined the residents’ status as protected tenants, they may have made no final determination regarding the ownership of the site. Justice Amit: “Since these were eviction proceedings before the magistrate courts [who have no competence to rule on ownership, D.S] it was not necessary to deal with ownership. In the end there was no legal remedy regarding ownership” )CR 24).

- The precise location of the property has not been identified. As the residents argued, it is possible that the property in question was not conclusively identified in the previous verdicts. Justice Amit asked counsel for the settlers: “What happens if in the procedure [to finalize title to the property] it turns out there is another [bloc] of property” )CR 26)?

The Court made no determinations on any of these issues, nor is it certain that the discussion of the substantive issues has been exhausted. However, there can be little doubt that the Court was also using their challenges to the parties in order to incentivize them to reach agreement and avoid the necessity of a court ruling.

3, The Court’s Pressure to Reach a Settlement Agreement

More than half of the hearing, and much of the Court’s attention were devoted to pressing the parties to reach an agreed settlement. They left little doubt as to their fundamental position, a position they did not and will not easily abandon: they indicate that the interests of justice will not be served by a Court verdict – any Court verdict. It is equally clear that the Court will go to great lengths to avoid handing down their ruling, and that perhaps the only way of making a judgment unnecessary is by reaching a settlement agreement. The Court has no power to impose one, but they indeed have the power of persuasion that is inherently vested in the Supreme Court. They were demonstrating their determination to use their influence to the hilt.

The Court gave the parties a one-page document outlining the principles of their proposed settlement. Quite remarkably, that document has not (yet) been leaked. However, they alluded to the document and its principles to such an extent that it’s fairly clear what they have so far proposed. And it is equally clear that the Court did not meander cluelessly into the minefield of Sheikh Jarrah. However facetiously they sent barbs at the press and the international community for allegedly bringing the “extraneous” realities of Sheikh Jarrah into the courtroom, the proposed agreement made it apparent that the judges were themselves intimately familiar with the politics involved, and with what issues mattered most to the parties. They were well-prepared, and tailored their proposals to address the unspoken sensitivities of the parties.

- The principles of the proposed settlement

The following are likely the general principles of the proposed settlement (which is not final, and remains negotiable):

- The settlers will assert their ownership of the property. The residents will not be required to openly acknowledge that ownership, but will need in some way to implicitly recognize it.

- The residents will indeed explicitly acknowledge their own status as protected tenants.

- In order to avoid their explicit acknowledgement of the settlers’ ownership, the residents will not be required to render rental payments directly to the settlers. The Court is proposing another yet undisclosed mechanism for making payment.

- The protected tenancy will commence afresh with the signing of the settlement agreement. To all intents and purposes, the right to be a protected tenant can be bequeathed by the original tenant to the next generation, but no further. Since recognition of the status of the residents implies that the protected tenancy began in 1967, left unaddressed, those rights are today likely close to their “expiration date”. Under the settlement agreement, the current tenant will become the “original tenant”. This means that the tenancy begins anew, and, in principle, the rights can expire in another several decades, and not as currently anticipated, in the near future.

(Towards this end, the Court proceeding concluded the hearing with a Court decision instructing the residents to submit, along with supporting documentation, the names of the protected tenants, for each of the homes who are party to the appeal. The residents have submitted the names and documents to the Court, and the settlers have been instructed to respond to that list no later than September 5).

- The residents will not be able to claim ownership of the property in any future legal proceeding, with one exception: during the process finalizing the formal title to the property (“hesder“), the residents will be entitled to claim ownership. Under these circumstances, the residents may move to have title and ownership vested in them, and nothing in the settlement agreement or its execution will be prejudicial to their claims. This allows the residents to accurately contend that they have not fully and irrevocably abandoned their claims of ownership.

Neither side accepted the proposal, nor did either of them reject it. The Court attempted to bridge the differences, so far unsuccessfully. The hearing ended with the Court stating that they have not despaired, and intend to continue pursuing possible agreement.

Even if it is not at all clear if the parties will be willing to accept the principles above, none of the proposed elements appears to be, in and of itself, a “deal breaker”, that is an insurmountable obstacle. It is easy to envisage both or one party accepting these terms, and equally to see either or both rejecting them. There is however one exception described below.

- Issues unaddressed by the proposed settlement

There is one outstanding issue that needs to be resolved, and without which the Palestinian residents will not under any circumstances consent to an agreement. The proposed settlement offers the residents the reasonable prospect (not the guarantee) of remaining in these homes for another sixty or seventy years. Under Section 131 of the Protected Tenancy Law, there is a specific list of those events that create sufficient cause to evict a tenant, most of which entail the tenant violating the tenancy agreement or tenancy laws. However, there is one exception: the section also provides that the owner may evict the tenant should he/she receive a building permit to demolish and/or build a new building on the site, provided the owner makes alternate housing available to the tenant. In this case, a tenant who is in full compliance with the law and the agreement may be evicted.

As noted, in the past, the settlers have declared their intent to raze the existing buildings in Sheikh Jarrah and to build a new settlement neighborhood in its stead. Should the settlers not explicitly waive this right, the Palestinian residents will be at their mercy. Without such a waiver, at any point in the future, the settlers need simply receive a building permit in order evict the residents. No reasonable person would agree to accept protected tenancy under conditions where for reasons beyond your control, you can be evicted.

The issue of potential settler construction was mentioned in passing during the court hearing, but not addressed. It appears certain to be one of the foci of the next hearing.

- The factors that will influence the decision to accept or reject a settlement agreement

What does each side get out of the settlement agreement, should it be concluded, and what issues will prevent such a settlement from being reached?

There are two kinds of issues that will influence the decision by each of the parties: the symbolic and the practical.

- The residents’ main consideration in favor of the proposed settlement – For the Palestinians, the settlement offers the prospect of remaining in the houses for the current and next generation, as opposed to potentially facing eviction in the weeks and months to come.

2. The residents’ considerations against the proposed settlement – There are significant risks and liabilities for the residents, both practical and symbolic, should they accept the status of protected tenant. Most substantially, they will live lives of uncertainty. Violation of the tenancy laws – making renovations, being a nuisance, or quarreling with the neighbors (almost a certainty when your neighbors are settlers seeking to drive you away) – are all causes of action sufficient to receive an eviction order. It is folly to assume that the settlers will be reluctant to pursue eviction proceedings in the future.

The symbolic price that the Palestinian residents are required to pay under the settlement agreement is no less daunting. The settlement agreement itself implies acquiescence to some of the more egregious elements of Israeli occupation. In doing so, it is emblematic of the reality that is the fate of all East Jerusalem Palestinians, whereby Israelis are endowed with “inalienable” rights, including the inalienable right of ownership built on bedrock and embedded in their humanity, while Palestinians have temporary, ever-endangered entitlements as tenants, ever hanging by a thread. It will live them in perpetual vulnerability deriving from the fragile, conditional and diminished rights of the residents, deprived from the ability to hold on to the most basic things in life for yourself and your family, and obliged to acquiesce to the humiliation entailed in confronting just how unequal you are to the “neighbors” – neighbors who want nothing more than to see you disappear.

3. The settlers considerations. The settlers are already in possession of a court verdict that may well allow them to evict the residents in the near future. They have the strong hand. Why would they possibly entertain a reversal of their fortunes by deferring for decades the prospect of eviction? Even if they know that due to current political circumstances it will be difficult to carry out the evictions any time soon, why would they agree to defer the evictions indefinitely?

It is more than possible that the settlers are biding their time. It is advantageous for them to allow the Palestinian residents to be seen as the obstacle to an agreement. However, if the residents agree to some variation of the Court’s proposal, it will not come as a surprise if the settlers will then reject it.

- The take-aways

So where do matters stand after a very significant, yet inconclusive round in court?

- The Court’s sub-text

Any attempt to read the mind of a court of law is always a perilous and highly questionable endeavor. That said, our reading of the court’s unspoken message and intent is the following (an interpretation for which the authors bear sole responsibility):

“Please don’t force this Court to write a verdict. We understand your plight, and are sympathetic. We want to leave you in your homes. But unlike those outside this room – the press, public opinion, the international community –we are not totally at liberty to form our own positions. We are an Israeli court and are compelled to rule according to Israeli law. We have listened to you and heard you, but we simply cannot give you the judicial relief you are seeking without deviating in the extreme from very well-established principles of Israeli law. As the Supreme Court we just can’t do that.

It would be technically easy to dismiss your motion in one laconic sentence: ‘we have decided not to intervene in the judgments of the lower courts’. However, aware of the consequences, we are trying not to abandon you to your fate. As we told your counsel “We are trying to help your clients” (CR, p. 9). We will use all of the powers of persuasion we possess to reach an agreed settlement that will accommodate some of your needs and address your major concerns – but not all of them. We are sensitive to the intangibles that are important to you. If achieved, the agreement will greatly reduce your risk of eviction for many years. It is not ideal, but all of the alternatives are much worse, and will put your families at grave risk.

For the sake of all involved, and not least of all for your own sake and that of your families, don’t compel us to write a decision. It is something we want to avoid, and a risk you don’t want to take.”

- The residents’ dilemma

The four families are facing a difficult and painful decision, undoubtedly one of the most important of their lives. It is a decision that highlights one of the fundamental existential dilemmas confronting the Palestinians of East Jerusalem daily since 1967. On the one hand, they are proud Palestinians, each in their own way willingly engaged in the Palestinian cause, while at the same time burdened with the daily struggle to protect and care for their families. Since 1967, the members of the Palestinian collective in East Jerusalem have oscillated between two poles of their national identities: resisting occupation and maintaining the Palestinian national equities in Jerusalem, while adapting to that occupation in ways that will secure the well-being of their families. There is an inherent tension between the two.

In the current context, this leads the residents to the following questions: Do they resist, or by necessity adapt? Do they “hold their ground”, amplify their story and resist an occupation that invariably diminishes their humanity, even at risk of jeopardizing their families; or do they adapt to a situation over which they have little control, reducing (but not eliminating) risk, while trying to take the sting out of some of the humiliations they endure under occupation.

It is a decision only they can make. However, the residents and others may be well-served by a sober and candid risk-assessment upon which they may base their decisions.

- Risk analysis

We consider these to be significant factors in play at this juncture, and that need to be considered in any risk analysis:

- The fates of the residents will be determined by an Israeli court of law, and no one on the bench will recognize the reality occupation, nor the authority of international law. While a just and moral outcome would be to award full ownership to the Palestinian residents on the basis of international law as applied to a belligerent occupation, calling for the court to accept these principles and rule accordingly is to demand that they do what they deem impossible for them to do. Advocating the impossible does not serve the purposes of weighing the risks.

- The resolute and growing public support for Palestinians living in Sheikh Jarrah, together with persistent international engagement, may well create political circumstances which will leave these families in their homes for the foreseeable future, even in the event that the Court upholds the eviction verdict. However, short of an occupation-ending agreement, we can envisage no trajectory whereby the residents will be awarded full ownership to the properties, however just that outcome might be. Assessing risk on the basis of a belief that an effective recognition of Palestinian ownership is achievable in some sort of foreseeable future would not be wise. It isn’t achievable now, nor will it be so in the foreseeable future.

- Every indication is that the Court is pressing for a settlement in order to avoid ruling in favor of the settlers. Should this come to a verdict, a ruling against the residents appears to be the likeliest outcome. There are those, however, who are asserting the opposite, encouraging the residents to reject a compromise on the assumption that the Court will rule against, not in favor of the settlers. Suggesting that the Court’s “… push for a settlement indicates their reticence in issuing a substantive ruling which would obligate them to rule against the settler group” is misleading, and does not accurately portray what is happening in court. It is dangerous for the residents to assume that the Court will likely rule against the settlers.

- The court’s attempt to neutralize the impact of the past, of history and of ideology inside the courtroom sent a message to the Palestinian residents, however unintentionally, implying that their past and their history don’t count. For the residents, this is just additional proof that the Court partakes in the same kind of colonial condescension that purports to “sanitize” occupation. This is, at the very least, highly counterproductive. The Court would do well to find an opportunity to correct that impression.

- While the senior members of the Israeli government would like to avoid the evictions, recognizing that they would have a devastating impact on vital Israeli interests, no one in official Israel has the courage to stake the steps that would make the threat of evictions disappear. The Court has been compelled to cover for the Israeli government’s abdication of responsibility. It is the Government of Israel, and not merely the courts, that will be held accountable for Sheikh Jarrah, and it would be well advised to assume responsibility and act accordingly.

- There is no guarantee that the settlers are willing to compromise, and there are compelling reasons for them not to do so. It has been reported that the residents rejected the proposed compromise, while the settlers accepted it. That is false. Neither side accepted it, nor did either side rejected it.

- Even under optimal circumstances, it will be very difficult for the residents to accept the settlement agreement. It is unwise and unjustified to underestimate just how difficult and painful the proposed settlement is for the Palestinian residents, and many of their concerns are well founded. If they accept, they will remain at risk, and endure humiliation.

- It is likely that the case before the Court will indeed be a precedent for the other eviction cases in Shimon Ha-tzadik. The legal issues are identical and the facts quite similar. That, however, is not the case regarding the eviction cases in Um Haroun and in Batan al Hawa. The issue of res judicata – previous court verdicts on the same issues and between the same parties – does not exist in Um Haroun and Batan al Hawa. It will likely be easier for the Court to engage in substantive deliberations in both of these cases, even if they will remain reluctant to do so for other reasons discussed.

- Israel’s reported approach to the United States with a request to exercise its influence on the residents of Sheikh Jarrah to accept the proposed settlement agreement would be, if true, an exercise in futility. Firstly, this demonstrates that there is no one in official Israel who has any relations worth speaking of with the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem. There is also no leadership in East Jerusalem to whom Israel may turn: all of the political leaders have been detained, expelled or otherwise deterred, and virtually all political activity quashed. When the United States moved its Embassy to Jerusalem, the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem severed ties with the US, while the US forfeited whatever leverage they may have had with them. Little has changed in that regard since Trump left office. The Palestinians of East Jerusalem are also alienated from the PA leadership in Ramallah. For years, Israel has been carrying out policies that seek to fragment Palestinian society in East Jerusalem. Today, when it’s in Israel’s interest to engage the Palestinians in and about Sheikh Jarrah, Israel is discovering that its policies of fragmentation have been so successful that there is no one left to engage.

- Should a verdict affirming the evictions be handed down, it is highly unlikely that the Israeli Government will allow them to take place in the months, perhaps years to come. However, if there will be an eviction verdict, there can be no doubt that at some point, that verdict WILL be carried out. All it will take is a coalition crisis, or a change in government, or a terror attack of such a magnitude that it will generate public lust for revenge. The residents should ignore any advice telling them “not to worry”.

- The unprecedented groundswell of support for the cause of Sheikh Jarrah has had a very significant and positive impact. As difficult as the circumstances of the residents may be, they would no doubt have been much worse without this large-scale and highly visible solidarity. However, this may well make the residents the captives of this successful campaign. Their status as symbol, of which they are very much aware, will make it very difficult for them to accept a settlement agreement, even if they would be otherwise disposed to do so. While maintaining solidarity is essential, so is giving the residents the breathing space necessary to make such a fateful decision without undue pressure, one way or another.

- A Very Tentative Bottom Line

- It appears less rather than more likely that this will all end in a settlement agreement.

- If there is to be no agreement, a Court ruling is inevitable, and a ruling against the residents and in favor of the settlers is more, rather than less likely.

- Regardless of what transpires, the grassroots protests and the international engagement are absolutely essential in maintaining the possibility of even a partially satisfactory outcome.

- While focus on Sheikh Jarrah is critical, so is resolute engagement on the other locations of potential displacement in East Jerusalem. By no means take one’s eye off Sheikh Jarrah, but it is also essential to focus on Um Haroun and Batan al Hawa.

- It would be wise for the Government of Israel to realize that consequences of evictions in East Jerusalem will be far more costly to Israel’s vital interests than any political price the Government may need to pay in order to stop them.

- The international community has noted with satisfaction the steps taken by the Bennett government that are intended to put Israel’s international relations on a new footing. Those efforts have met with a good deal of success. Evictions in East Jerusalem are not a routine event, and they will create a crisis of such proportions that all of Israel’s recent diplomatic achievements will disintegrate.

- It is not too soon to prepare for the consequences of a Court ruling that allows the evictions to take place. Such a verdict itself may suffice in causing an eruption of violence, even without any evictions taking place.

- Even if there will be a court verdict in favor of the settlers, there still will be the possibility, however remote, of preventing the evictions. These possibilities need to be explored even now.