There can be little doubt that the prospect of the eviction or displacement of Palestinian families in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah was a major contributory factor in the outbreak of violence between Israel and the Palestinians in May 2021. With the outbreak of violence between Israel and Gaza, the issue of Sheikh Jarrah became more visible, and the claims and counter-claims a banner under which the contesting parties mustered support. The Israeli Foreign Ministry, echoed by many others, asserts that the events in Sheikh Jarrah are no more than “a private real estate dispute”. Palestinian voices and international organizations assert that displacement in Sheikh Jarrah is yet another chapter in the ongoing Palestinian nakba that commenced in 1948.

The pending evictions in Sheikh Jarrah are by no means unique, and there are at least two other East Jerusalem neighborhoods or communities, Batan al Hawa and Al Bustan, both in Silwan, which face similar prospect of large-scale displacement.

In each of these cases, the issues of displacement and eviction are being played out in Israeli courts and under Israeli law, while at the same time raising important questions concerning the rights and protections under international law. However, the legalities and statutory intricacies disclose only a part what dramatic developments unfolding in East Jerusalem.

Consequently, our discussion will zoom out in order to explain the historical background and context of the current threat of large-scale displacement in the heart of Jerusalem. We will examine the nature of Israeli policies in East Jerusalem, and the manner in which Israeli laws are being used and abused. This is also the stories of the protagonists – the Palestinian families currently at risk, their stories, and the settlers who seek to replace them. At the end of the day, the answers to these questions will lead to one, inescapable and overwhelming meta-question: does Israel have the legal and moral right, and the necessary legitimacy and authority, to

displace the residents of entire Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, and replace them with settlers?

1. Executive Summary

- Background

· Jerusalem, 1949-1967

- Land expropriation and the large settlement neighborhoods in East Jerusalem

· Two exceptions: the cases of forceful displacement in East Jerusalem since 1967

- The Current Policies of Large-Scale Displacement of Palestinians in East Jerusalem – 2021

· The Scope of the Potential Evictions/Displacement

- Targeted Areas

· The Geopolitical Ramifications of Displacement/Evictions

- Palestinian Equities, Settler Equities

· Protected Tenancy Rights as Allegory

- The Real Questions Relating to Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan

5. The Way Forward

- Executive Summary

When Israel annexed East Jerusalem in June 1967, no Israelis resided there, and its population of approximately 69,000 was exclusively Palestinian. At the beginning of 2020, there were 227,000 Israelis residing in East Jerusalem, 99% of whom live in the large settlement neighborhoods of East Jerusalem built by Israel since 1967.

In order to build these large settlement neighborhoods, Israel has, since 1967, expropriated one third of the privately owned land in East Jerusalem (approximately 24 sq. km.), overwhelmingly from Palestinians. Israel has built more than 56,000 residential units for Israelis on these lands.

While the expropriations caused the Palestinians to lose a significant part of their private assets, the construction of the large settlement neighborhoods did not entail the displacement of Palestinians. With one glaring exception in June 1967, Israel has not at any point since 1967 engaged in the large-scale displacement of Palestinian populations in East Jerusalem. The Palestinians of East Jerusalem numbered 69,000 in 1967. In 2021, that population has grown into a steadfast collective numbering more than 360,000 souls.

During the past two-three years, Israeli policies on displacement have radically changed. In two areas in East Jerusalem, that include four neighborhoods, the government of Israel, directly or hand in glove with the East Jerusalem settler organizations with whom they are complicit, have instituted eviction proceedings

against 160 Palestinian families, 60 in two areas of Sheikh Jarrah and 100 in Batan al Hawa, Silwan. In addition, on the horizon looms the possible demolition of approximately 78 buildings with 130 households in the Al Bustan area of Silwan.

All of those at risk of eviction are Palestinian. Their only “crime” is residing in neighborhoods or communities targeted for ideological reasons by the settlers of East Jerusalem. As has invariably been the case in the past, once the evictions take place, all of the homes will be turned over to members of these settler organizations.

Never before has Israel targeted entire neighborhoods or communities in East Jerusalem, in an attempt to replace their Palestinian residents with settlers. Today, that is exactly what is happening.

2. Background

Jerusalem, 1949-1967

Between 1949 and 1967, Jerusalem consisted of two largely homogeneous, cities. To the West, there was an Israeli city ,38 sq.km in size, populated only by Israeli residents, with the exception of several hundred Palestinians in a small part of Beit Safafa, and a handful of others scattered elsewhere. To the East, there was a city populated solely by Palestinians. To all intents and purposes, prior to 1967, these were two nationally homogeneous cities.

The homogeneity of these two Jerusalems was the direct result of the 1948 war. That war led to the displacement of 20,000-30,000 Palestinian residents of the city (depending on how one defines the boundaries of Jerusalem). The war also displaced approximately 2,000 Jews in Jerusalem, mostly from the Jewish Quarter of the Old City. A couple of hundred of those displaced were from the two neighborhoods in Sheikh Jarrah under discussion.

On June 27-8, shortly after the 1967 war, Israel annexed 70 sq. km that had been under Jordanian rule, and incorporated these areas, which have come to be known as East Jerusalem, into a “united” municipal Jerusalem. Approximately 69,000 Palestinians resided in the newly annexed areas, to whom Israel extended permanent residency status, but not citizenship. At the time, there were 197,000 Israelis residing in West Jerusalem, and, as noted, none in East Jerusalem.

Land expropriation and the large settlement neighborhoods in East Jerusalem

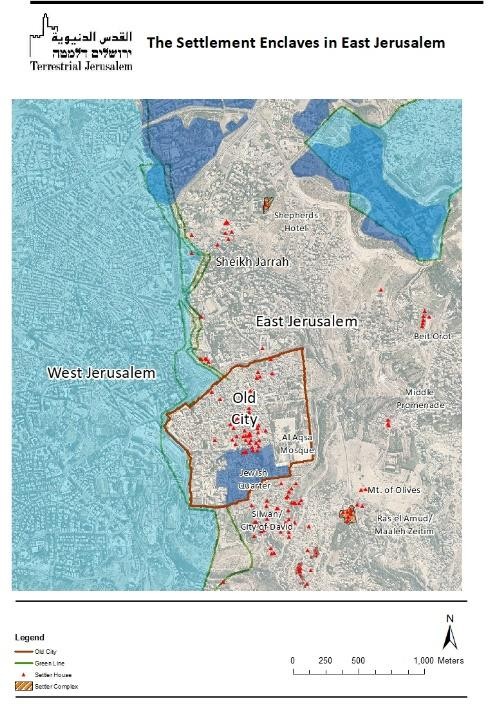

Fifty-three years later, approximately 225,000 Israelis reside in East Jerusalem. Except for approximately 3,000 settlers who live in the settlement enclaves implanted within the existing Palestinian neighborhoods, all reside in the large settlement neighborhoods built by the Israeli government since 1967.

The major legal mechanism that was used to enable large scale Israeli residency in East Jerusalem was the Lands Ordinance – 1943 (Acquisition for Public Purposes). The ordinance was used by the government of Israel to expropriate almost a third of the privately owned lands in East Jerusalem, overwhelmingly, but not exclusively from the Palestinian population of East Jerusalem. Since 1967, Israel has built more than 56,000 residential units for Israelis on these lands. Less than 600 units were built for Palestinians, the last of which was in the 1970s.

The construction of the large settlement neighborhoods in East Jerusalem took place without large-scale displacement of Palestinian residents. Palestinians were not forced from their homes, nor did the construction required more than a small number of demolitions.

There are two noteworthy exceptions.

Two exceptions: the cases of forceful displacement in East Jerusalem since 1967

- The Mughrabi Quarter

On the night of June 10, 1967, hours after the ceasefire in the 1967 war, Israeli bulldozers, acting under orders of the Minister of Defense and the Mayor, razed 135 homes located in the Mughrabi Quarter, adjacent to the southeast containment wall of Haram al Sharif/Temple Mount. The site is now the location of the monumental Western Wall Plaza. Many hundreds of Palestinians were displaced, and there was one fatality.

In the ensuing months, tens of additional buildings were razed. There was no pretense of legality, and no attempt to justify the act based on military necessity.

Since then – and until the pending displacements in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan – there have been no other cases of large-scale displacement of Palestinians in East Jerusalem.

- Displacement of targeted families in Silwan and the Muslim Quarter

- A coordinated governmental scheme

In the mid-1980s, the government of Israel led by Ariel Sharon and a tightly knit, clandestine group of officials, carried out a covert and coordinated campaign to take over targeted Palestinian properties in the Old City and Silwan, and turn them over to the settler organizations that had fingered these properties in the first place. Since some of the current government policies being used in Sheikh Jarrah and in Silwan are highly reminiscent of the methods that have been used by the government in the campaign implemented in the 1980s and 1990s, we will examine them in some detail.

In 1984, a committee was established whose mandate was to coordinate virtually between all relevant Governmental authorities – the Israel Lands Authority, the Custodian of Absentee Property, the Custodian General, the Ministry of Religious Affairs, the Ministry of Construction, and many others – in service of the settler enterprise in the existing Palestinian communities in East Jerusalem.

The goal of these efforts was to harness all relevant governmental bodies and authorities so that individual homes and buildings selected by the settlers could be taken from their Palestinian residents and transferred exclusively to the settlers of the Muslim Quarter of the Old City and Silwan.

It should be noted that this campaign targeted individual homes in specific locations, but not large-scale displacement of entire neighborhoods and communities.

However, to this day, many of the settlers’ holdings in the Old City and Silwan are the direct result of the covert Government campaign that took place between 1985 and 1992, which succeeded in displacing several Palestinian families.

- The Klugman report

These covert Government activities in the Old City and Silwan were exposed to the public by one dramatic event: on the night of 9 October 1991, Elad settlers, in semi- military fashion, took over eleven dwellings in the Wadi Hilweh sector of Silwan, sparking both a domestic and international uproar.

In August 1992, newly elected Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who opposed these settlements, established an inter-departmental board of inquiry, headed by the Director General of the Ministry of Justice, Haim Klugman, with the mandate to examine the legality and the irregularities of the governmental transfer of properties to the settlers in East Jerusalem.

The Findings of the Klugman Committee

In September 1992, the Klugman Committee submitted its findings to the Israeli Cabinet, disclosing the numerous irregularities and illegalities within the governmental bodies investigated, in all matters relating to the transfer of properties to the East Jerusalem settlers. These are just a partial list of those findings:

- The settler organizations identified properties to be targeted by the government for seizure. The State subsequently granted the settlers control over these properties, based on often questionable documentation, arranged for and confirmed by the settlers themselves.

- Properties were systematically allocated based on criteria that violated the principles of equality, and in violation of rudimentary procedures, that is: exclusively to the settlers, and no one else.

- The Absentee Property Custodian failed to exercise even minimal judgment and discretion. He declared properties “absentee properties” based on questionable evidence submitted by the settlers, without knowledge of the

Palestinian residents. He then allocated all these properties to the same settlers who had submitted the questionable evidence.

- No tenders had been issued, and it was the political echelon of the Ministry of Construction that instructed which settler association would receive which property.

On 13 September 1992, the Israeli Cabinet adopted the findings of the Klugman Committee Report, and issued a series of resolutions instructing relevant bodies (the Ministerial Committee for National Security, the Attorney General, the Ministers of Construction and Finance, etc.) to carry out investigations in those areas under their authority, and to take measures that would prevent the recurrence of the policies detailed in the Report.

The Klugman Committee: Achievements and Failings

In the ensuing years, the policies detailed in the Klugman Report indeed ground to a halt. The systematic use of the Absentee Property Law was stopped, never to fully resume. Governmental support of the settlers indeed continued, but by other, much more modest means.

However, in the wake of the Report, no measures were taken to redress the illegal and irregular steps advanced by the government for the exclusive benefit of the settlers:

- No property was returned to the public or to its previous residents. In fact, there is one Palestinian family in Silwan which continues to fight its displacement in an Israeli court – displacement that resulted from the actions described in detail in the Klugman Committee Report.

- No criminal investigations and no disciplinary actions took place.

- None of the tens of millions of sheqels illegally allocated to the settlers was returned to the public coffer.

- Whereas the State attorney’s office has repeatedly claimed to the Supreme Court that they “…did not take lightly the findings of the Klugman Committee Report and the immediate need to prevent a recurrence of the policies detailed in the report”, nothing happened.

- The burial of the State Comptroller’s Report: the government resolution adopted after the Klugman Report instructed the State Comptroller to carry out an investigation under Article 21 of the State Comptroller’s Law. In 1997, State Comptroller Miriam Ben Porat informed Prime Minister Netanyahu that the findings in that investigation were so serious that its release would cause grave damage to Israel’s international image, and she advised to bury the report. A Knesset member took the matter to the High Court of Justice asserting that a report that was based on a cabinet resolution could not be

stopped this way. The day before the Court hearing, the Prime Minister – Benjamin Netanyahu – convened the Cabinet and reversed the resolution that ordered the investigation, and the Comptroller’s report has never been released.

3. The Current Policies of Large-Scale Displacement of Palestinians in East Jerusalem – 2021

Almost 30 years after the Klugman report put a stop to the governmental displacement efforts of targeted Palestinian families in Silwan and the Old City, there has been a resurgence of very similar policies and methods. The major difference is that today, the targets are not individual Palestinian families, but entire neighborhoods and communities.

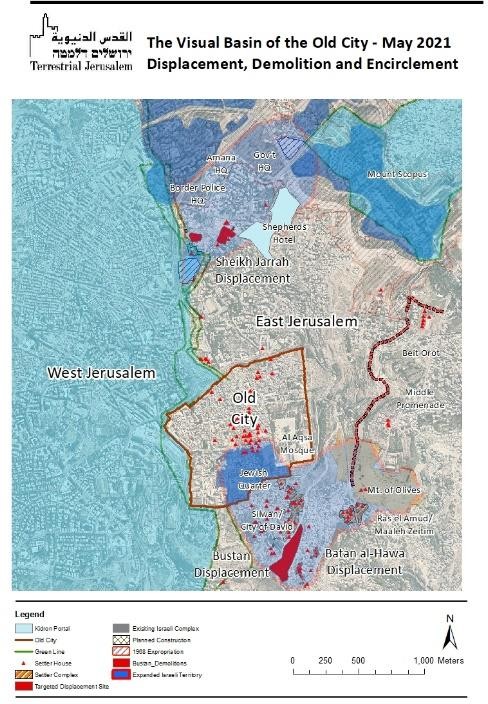

There are currently four communities/quarters in two neighborhoods which are exposed to the possibility of large-scale displacement: Shimon Ha-Tzadik (Karem Ja’uni) and Um Haroun in Sheikh Jarrah, and Batan al Hawa and Al Bustan in Silwan. In the former three, the threat of displacement derives from eviction orders, and in the latter the danger is the result of pending demolition orders.

The Scope of the Potential Evictions/Displacement

In the two areas targeted by the settlers, in Silwan and Sheikh Jarrah, eviction proceedings have been instituted against c. 160 Palestinian families (60 in Sheikh Jarrah and 100 in Batan Al-Hawa). These cases are currently before the courts.

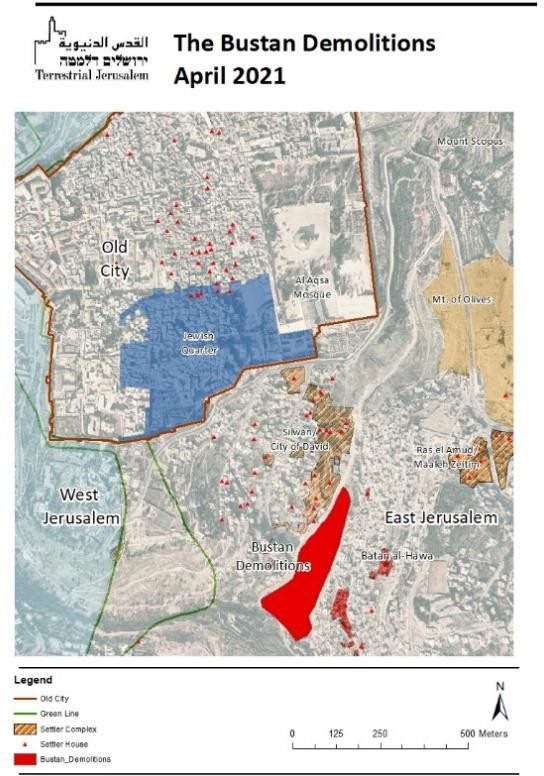

Eviction orders have been handed down and may be executed in the immediate future regarding 50 of these houses in Sheikh Jarrah, and 85 houses in Batan al Hawa. In addition, the prospect is looming of the demolition of 78 buildings home to 130 families in the Al Bustan area of Silwan.

Out of these, the Israeli Government, directly or in close collaboration with the settlers have already evacuated 22 families from 11 structures.

As of today, there are in total c. 135 families from 45 homes (50 in Sheikh Jarrah and 85 in Batan Al-Hawa) in imminent or proximate danger of eviction, in addition to 130 families in 78 houses with demolition orders in the Bustan. [Note – based on data collected in cooperation with Peace Now’s Settlement Watch].

As noted, never before has the Government of Israel engaged in the large-scale displacement of Palestinians in East Jerusalem. Nothing of this scope has been witnessed in East Jerusalem since 1967.

This is without precedent.

Targeted Areas

We will briefly describe each of the targeted neighborhoods. Shimon Ha-Tzadik (Karem Jauni), Sheikh Jarrah

- Location – The Shimon Ha-Tzadik compound is located in Sheikh Jarrah, a Palestinian neighborhood that began to develop outside the walls of the Old City in the mid- 19th Century. Shimon Ha-Tzadik is located along the Nablus Road, one km. to the north of the Old City’s Damascus Gate, and is nestled among the stately houses of the Palestinian elite in Sheikh Jarrah.

This is the location of a burial grotto which has been the site of Jewish pilgrimage commencing, at the latest, in the 13th Century. It is associated with the burial site of Shimon Ha-Tzadik (Simon the Righteous), identified as the High Priest during the Second Temple Period.

- Pre-1948 – In 1876, two Jewish religious associations, the Sephardic Community Council and the General Council of the Congregation of Israel purchased rights to the tomb and to an additional 17.5 dunams (about 4.4 acres) adjacent to the tomb, dividing the land around the tomb between them. In the northern portion of the plot, a small complex of buildings was built, housing approximately 50 residents. The southern part of the site remained empty.

At the beginning of 1948, with the outbreak of hostilities that also engulfed Jerusalem, the residents of Shimon Ha-Tzadik were evacuated upon instructions from both the Hagana and the British authorities.

- 1948-1967 – In the aftermath of the 1948 war, Sheikh Jarrah became part of East Jerusalem, and fell under Jordanian authority. In a cooperative endeavor between UNWRA and the government of Jordan, homes for 28 Palestinian refugees were built on the southern part of the site. 28 Palestinian refugee families concluded long-term lease agreements with the government of Jordan (three years in duration, with right of renewal) with nominal rental payments.

- Post-1967 – In the wake of the 1967 war, the two Jewish associations that had acquired rights to the Shimon Ha-Tzadik compound took legal action against the Palestinian residents, invoking Israeli legislation enacted in 1970 empowering those who lost property in East Jerusalem to recover that property. (As we shall see, the ability to recover property lost in the war in 1948 was limited to East Jerusalem. Consequently, Jews could recover property lost in the war, Palestinians could not).

- 1987 court verdict: Palestinian residents as protected tenants – In 1987, in circumstances that have been hotly disputed until today, the court extended the validity of a court verdict to an agreed arrangement between the parties – known as the Toussia-Cohen agreement of 1982 – whereby the ownership rights of the religious associations were acknowledged, but the Palestinian residents of these homes were recognized as protected tenants. [Note: The Palestinian

residents adamantly insist that their legal counsel failed to inform them about the agreed arrangement, and contend that the rights acquired by Jewish associations in 1876 did not transfer the rights of ownership to these two trusts. These issues remain in disputes in the current court proceedings].

- Purchase of rights by settlers – In 2003, Nahlat Shimon Ltd. A subsidiary of a Corporation registered in the United States, and associated with the East Jerusalem settlers, purchased the rights of the two Jewish trusts in Shimon Ha- Tzadik. Between 1988 and 2017, the settlers were successful in evicting seven Palestinian families, and currently there are eviction proceedings pending before the courts in relation to another 14 buildings with 45 families, in which the corporation claims sundry violations of protected tenancy laws by the residents. We will deal with the fragility of the rights entailed in the protected tenancy laws below.

The fourteen buildings that currently parties to eviction proceedings before the courts are the very same houses built by the UN and Jordan in the 1950s.

The most imminent potential evictions are in a case currently before the Supreme Court, where the court granted a stay of execution applying to one house with five households. Should that stay not be granted, the eviction can take place at any time.

Um Haroun, Sheikh Jarrah

- Location – Immediately to the west of the Nablus Road in Sheikh Jarrah, opposite Shimon Ha-tzaddik, is the small neighborhood of Um Haroun.

- Pre-1948 – In 1891, Jews who had immigrated primarily from the Georgia region of the Caucasus built their homes in this area. The neighborhood came to be known as Nahlat Shimon, or the Georgians’ Neighborhood. There were approximately 40 homes in the neighborhood, and 4 synagogues.

Like its sister neighborhood of Shimon Ha-Tzadik, the neighborhood was abandoned in 1948 on instructions by the Hagana and the British Mandatory authorities. In large part, Israel resettled the families in the homes of Palestinian refugees in West Jerusalem, who had fled or been expelled as a result of the hostilities.

- Post 1948 – After the war in 1948, the Jordanian government housed Palestinian refugees in these homes. These remain core of the Palestinian families who reside today in Um Haroun.

- Post-1967 – In the wake of the 1967, the management of these homes came under the authority of the Custodian General, an autonomous official in the Ministry of Justice. Formally, it is the responsibility of the Custodian General to manage the properties for the Jewish owners, the whereabouts of whom are not known. In reality, since the 1990s, the symbiosis between the settlers and

the Custodian has become nothing less than collusion. Throughout the years, the Custodian has “released” properties, or sold, or expedited the sale of all these properties to the settlers of East Jerusalem settlers.

[Note: It is important to distinguish between the Custodian General and the Absentee Property Custodian. Throughout Israel, and in East Jerusalem, it is the responsibility of the Custodian General to protect and maintain the property on behalf of the missing owners. In contrast, the Absentee Property Custodian takes control of properties in Israel and East Jerusalem of those Palestinian refugees who fled in 1948. Under Israeli law, the refugees forfeit all rights to the property, and the property is almost invariably transferred to government ownership.]

- So far, the Custodian General, like the settlers across the street in Shimon Ha- Tzaddik, has instituted eviction proceedings (directly or by means of the settlers with whom the Custodian cooperates) against approximately 40 families residing in 16 structures, based on the same or similar claims of violation of protected tenancy laws.

Batan al Hawa, Silwan

- Location – Batan al Hawa is a part of Silwan located on the southern slopes of the Mount of Olives, beneath the settlement of Ras al Amud/Ma’aleh Zeitim and immediately above the Kidron Valley/Wadi Na’ar.

- Pre-1948– In the late 19th century, a group of Yemenite Jews immigrated to Jerusalem. Shunned by the existing Jewish community, they established their homes on the slopes above the Kidron valley. Disturbed by the abject poverty in which the Yemenite Jews were compelled to live, the established Jewish community created a trust, called “the Benvenisti Trust”‘ with the chief rabbis of Jerusalem as trustees. The objective of the trust was to construct a 72-room residential complex in Batan al Hawa. Once the complex was completed, additional families, both Yemenite and Arab, build additional homes in the vicinity of the complex. The area came to be known as the Yemenite Quarter.

Over the years, many of the Yemenite residents moved out of the area. In 1938, the British authorities ordered the remaining Yemenite Jews to abandon their homes for the sake of their own safety. The buildings remained vacant until 1946, and were rapidly deteriorating. The Benvenisti Trust then empowered a Palestinian resident of Batan al Hawa to dismantle the homes and sell the masonry. By the end of the 20th century, only one of the trust’s homes remained.

- Post- 1948 – During Jordanian rule, the Palestinian engaged by the trust sold parts of these lands to third parties, and the numerous land transactions in Batan al Hawa persisted well after the 1967 war. Many of the new houses were built on lands of the Benvenisti Trust, while many others built nearby.

- In the 1990s, an interdepartmental governmental committee conducted a land survey in Batan al Hawa in order to locate the lands owned by the Trust and by Jews before 1948. The Ateret Cohanim settler organization was an active participant in that survey. In 2001, members of Ateret Cohanim, who had no connection to the Benvenisti Trust, asked to be appointed as trustees. The Custodian General consented, and the court approved their nomination as the trustees. The area purportedly owned by the trust was delineated based on material provided by the settlers’ surveyor. A year later, the Custodian General released the lands to the ownership of the Trust. In 2006, the Custodian General sold four additional properties under his management to the Trust. The residents were not told of the prospective sale, and only the settlers had the opportunity to bid for the property.

- In recent years, the settlers (in their incarnation as trustees of the Benvenisti Trust) have instituted eviction proceedings against 100 families in Batan Al- Hawa, and so far managed to evict 13 of them. The District Court has already ruled against 19 of the families, and their cases are currently on appeal before the District and Supreme Court.

Al Bustan, Silwan

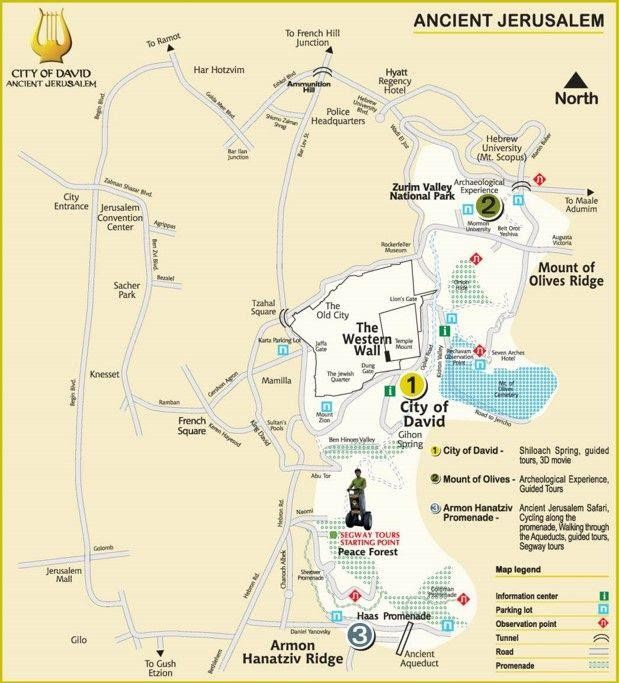

Location – Al Bustan in Silwan is a wadi nestled at the base of Batan al Hawa. 38 dunams in size, Al Bustan is the geographical link between Wadi Hilweh (the City of David, already largely under the control of the settlers) and the fledgling settlement in Batan al Hawa. Due to its strategic location, Al Bustan has long been destined to be an integral part of the renewed biblical realm ringing the Old City, being dubbed “the Kings Valley” or “Kings Garden.

Consequently, both Governmental and Municipal Authorities and the settlers have declared their intent to demolish the homes in Al Bustan. There are today in excess of 100 buildings in Al Bustan. Since zoning plans do not allow for any construction in the area, the only legal buildings in Al Bustan are the few that were standing prior to 1967. All the others were built without permits.

Both in 2005 and 2009 the Jerusalem authorities announced their intention to demolish the homes in al Bustan. Both times they were beaten back by a vociferous

However the plans to demolish homes in Al Bustan proceeded. There are currently more than 78 legally valid demolitions orders against the buildings in Al Bustan. In recent years, the Municipality has agreed that the Court will grant a stay of execution regarding these demolition orders, so that the residents may advance a town plan that would legalize much of the construction.

In February, the Municipality reversed its position and asked the Court to rescind its stay of execution. The Court has granted a stay until August 2021 (see our previous report here).

These demolitions would entail the demolition of 78 buildings or more, housing 130 households, and displacing several hundred souls.

The Geopolitical Ramifications of Displacement/Evictions

Neither the government nor the settler organizations with whom it cooperates are randomly targeting these four Palestinian neighborhoods in East Jerusalem.

The settler movements of East Jerusalem are driven by an ideology informed by a “thermal map”. Not every area “glow” with

equal intensity for these settlers. They will not be found targeting outlying Palestinian areas in East Jerusalem, such as Beit Hanina or Sur Bahir, for settlement. It is only those areas which resonate in some way with ancient biblical history on which they set their sights, primarily within the Old City, and the visual basin around the Old City.

These areas include, first and foremost, the City of David (the ridge from which biblical Jerusalem developed), the Yemenite Quarter, the Mount of Olives, Shimon Ha-Tzaddik etc.

This desire not only to reside in, but to restore in some way an ancient Biblical realm is what motivates both the government and the settlers to establish the settlement enclaves of East Jerusalem.

As we have noted, there are approximately 222,000 Israelis residing in the large settlement neighborhoods of East Jerusalem. These largely exclusive Israeli settlements were built alongside, but not within, existing Palestinian built up areas. In contrast, the desire restore the biblical areas of Jerusalem has led the settlers to create settlement enclaves within existing Palestinian neighborhoods. These are enclaves because a) they are an individual house, a cluster of houses or a small complex inside a Palestinian neighborhood much larger in size and population, and

b) contrary to the large settlement neighborhoods, they are not geographically connected to pre-1967 Israel.

It has long been the goal of the settler organizations to transform these settlement enclaves not only into an extension of pre-1967 Israel, but to create a ring of biblically motivated settlements around the Old City, such as the settlement houses in the Muslim Quarter-the Jewish Quarter-Silwan-Ras Al Amud-Mount of Olives-Beit Orot-Shimon Hatzadik.

This map, produced by the Elad settler organization of Silwan articulates this aspiration well.

In 2005, under the government of Prime Minister Sharon, these aspirations became government policy by means of the creation of a major national project dubbed “The Strengthening of the City of Jerusalem Project”, which seeks to “strengthen the

status of Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Israel…[through] the restoration, development and maintenance of the basin of the Old City and the Mount of Olives”. The objective of enclosing the Old City has driven Israel policy ever since.

The boundaries of the governmental Old City Basin Project fully integrate the targeted neighborhoods of Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan into the strategy of encircling

the Old City. Each settlement is adjacent to a “national park” with a biblical theme, and integrated into so-called “pilgrimage trails”.

For the first time since 1967, the settler enclaves in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan are being transformed from settlement enclaves into extensions of pre-1967 Israel, a development that has far-reaching ramifications not only for the universal cultural integrity of the Old City, but for the very possibility of future political agreement.

This map displays how Jewish settlements in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan, coupled with public institutions like a Yeshiva and Police Headquarters, national parks and trails etc.

conspire to radically change the character of the historic, cultural and religious core of Jerusalem, the Old City, by ringing it with a biblically themed settler realm. And it is in these are the geopolitical crosshairs that Sheikh Jarrah, Um Haroun, Batan al Hawa and Al Bustan now find themselves.

Palestinian Equities, Settler Equities

All of the Palestinian families currently under threat of being displaced have been living in these homes for decades, most for 65 years and more. They are not squatters. They did not arbitrarily break into these homes. Some were placed in these homes by the Jordanian Authorities, having been made refugees in the 1948 War (precisely as Israeli authorities housed Israel’s refugees in homes from which Palestinians fled). Others entered the homes with the consent of the pre-1948 Jewish owners.

Who has formal property rights to the properties in question is one of the main issues with which the Israeli courts of law are now contending. We will address these legal issues below. However, it is important, from the outset, to bear in mind the human dimension of property rights, alongside of the legal issues.

- No one on earth has deeper roots in these homes, or a family heritage going back generations, or the wealth of memories associated with “home”, than these Palestinian families who have been living in them for decades. Certainly not the settlers destined to take them over.

- With the exception of the homes in Um Haroun and a single house in Batan al Hawa, where Jews resided prior to 1948, no one except these Palestinian families have ever lived in the buildings in question.

- Not one of the original owners of the land from the period prior to 1948 has returned to live or work in Sheikh Jarrah or Silwan. Not one.

- Likewise, not one of the settlers who has attained possession of a property in Sheikh Jarrah or Batan al Hawa has any personal or familial connection to the property. The only connection is ideological. The settlers have no connection to the sundry and largely defunct trusts that had rights to the properties decades ago. In spite of that, the Rabbinic Courts and the Trusts’ Registrar, with the consent of the Custodian General, customarily appoint the settlers as trustees, with the full knowledge that their goal is the takeover of properties in which Palestinian families reside.

- All of those whose evictions are sought are Palestinian. They have been targeted for eviction by the settlers because they reside in locations which the government of Israel and the settlers aspire to control for the reasons cited above.

- The Custodian General customarily releases properties and private family trusts exclusively to the settlers, whether directly or by means of facilitating transactions with the pre-1948 owners. The Custodian General has not released properties to Palestinians in this area, nor provided them the opportunity of acquiring rights to these properties.

- The recently concluded land registry in Um Haroun was carried out with the knowledge and active input of the settlers; the Palestinian residents of Um Haroun were left in the dark.

- For a protracted period, the lead lawyer of the settlers also represented the Custodian General in eviction proceedings against the residents of Sheikh Jarrah. A settler activist was chosen to run the department in the Custodian General’s office responsible for East Jerusalem.

- The Custodian General sold properties under his management, but without bidding and exclusively to the settlers. The residents were not informed of the sale.

The conclusion is unequivocal: in these areas, the government of Israel and the settlers are to all intents and purposes one and the same. The “public interest” is identical to the settler interest. The Palestinian families are not considered part of “the public” and their equities are simply not a factor.

Protected Tenancy Rights as Allegory

The court verdict/arrangement of 1987 cited above did not only concede that the ownership rights to the site were vested in the two Jewish trusts, but that the Palestinian residents were recognized as “protected tenants”.

Protected tenancy laws emerged during the British mandate in response to housing shortages, and underwent amendments and modifications under Israeli legislation. These laws create a complex mechanism of tenancy for those in possession of properties the leases to which have expired. The law creates a labyrinth of rules and regulations which, under certain circumstances, lets a tenant remain in the property indefinitely and pay a nominal rent for course of his or her natural life. It is the bane of the landlords, who are able to exact only a fraction of what they could earn were the property unfettered by protected tenancy.

There is a statutory list of events that give rise to a “cause to evict”, allowing the property owner to evict the tenant and recover the full property rights. The tenant must scrupulously maintain the lease agreement. Rental payments must be paid, and the tenant is forbidden from making any additions, renovations or extensions to the property, and the state of the property is “frozen”, save routine maintenance.

Leaving the property for any period of time is “abandonment”, and a “cause to evict”, as is “causing a nuisance”. The protected tenancy rights cannot be transferred to a third party without giving a right of first refusal to the owner, nor may it be leased to a third party without the landlord’s consent. The tenancy rights expire with the death of the tenant, and pass on to an heir only subject to fulfilling a strict list of conditions (such as being an immediate family member who lived in the property immediately prior to the deceased tenant’s death).

Most importantly for our discussion, it suffices that the landlord wants to make use of the property him/herself, or to demolish the property and build upon it, or do a total renovation of the property, for there to be sufficient cause to evict the tenant. In these two cases only – the owner using the property or demolition/renovation is the tenant entitled to alternate, equivalent housing, or monetary compensation.

This situation clearly indicates how the protected tenancy of the residents in Sheikh Jarrah are fragile and greatly limited, capable of protecting their rights temporarily. These laws make the eviction of the Palestinian residents no less certain, but just deferred for an undetermined period of time. And until then, their rights hang by a thread.

In order to remain, their living quarters must be frozen in time, as they were in 1967, with no major improvements. If they leave for any period of time – for studies, etc. – they jeopardize their rights. If they have altercations with their settler neighbors, it’s a cause for eviction. But most importantly, the owners may at any time evict them if they want the property for their own use or want to demolish and build on it.

The settlers, particularly those in Sheikh Jarrah, have not only announced their intention to raze the current structures and build an entirely new settler complex, they have in the past filed statutory plans to do just that.

So to all intents and purposes, the solution cited as the “salvation” of the residents of Sheikh Jarrah – protected tenancy – is no solution at all: it does not prevent

eviction, it merely defers it, while life in their homes in the interim is strictly confined. The only way the Palestinian resident may remain in the only homes in which they have ever lived is by acknowledging their temporary and ever-vulnerable status as protected tenant.

The issue of the protected tenancy status of the residents of East Jerusalem resonates well beyond the borders of the neighborhood, and is emblematic of the most fundamental characteristics of the Palestinian plight throughout East Jerusalem, the most prominent of which is permanent vulnerability.

The Palestinians of East Jerusalem are not citizens of Israel, and while they are politically disempowered, they are not entirely without rights. However, the rights of Israeli citizens are “inalienable” rights, built on bedrock and embedded in their humanity. The rights of the Palestinians are “alienable” rights, limited and stunted, ever hanging by a thread. As with the rights of protected tenancy, the property rights and rights of residency of East Jerusalem Palestinians are vulnerable, and can be rescinded by government in ways that the rights of Israelis living close by may not.

The existential essence of the Palestinian condition in East Jerusalem is mirrored in what is transpiring in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan. Insofar as the government and settlers are keenly devoted to take control of these neighborhood, and the inadequacy of the protections offered by the limited rights of the Palestinians, it would appear that under current circumstances, the fates of Palestinian Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan are sealed.

The residents of Sheikh Jarrah are subject to an extreme manifestation of what all the Palestinian residents are being subjected to: perpetual vulnerability, uncertainty about one’s ability of holding on to the most basic things in life, and a fate to be determined by people who, at best, don’t care about you, and at worst, are willing to rescind your most basic rights without batting an eyelash.

4. The Real Questions Relating to Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan

Sheikh Jarrah has been described as a routine real estate dispute. It is technically correct that this is a dispute over land, but there is nothing routine about it. In fact, asserting that this is about “real estate” is so blatantly oblivious to what is really happening that it can be believed only by means of false innocence and cultivated denial.

The interpretation of the intricacies of the protected tenancy laws, along with other complex issues like statute of limitations, ownership under Ottoman property laws etc. are at the heart of the various legal proceedings dealing with the eviction suits against the residents of Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan.

[Note: Since the effective law in place is that of Israel, we limit our discussion to provisions of Israeli law. It remains crystal clear that under international law, it is

illegal for the occupier to both transfer its own population to the occupied territory, and to forcefully displace the population under occupation.]

These are no “kangaroo courts”, where the outcome is entirely clear in advance. The playing field is indeed very much tilted in favor of the government and the settlers. There is close cooperation between the state and the settlers. The judge is invariably Israeli who rules based on laws that aspire to serve an Israeli public – and the Palestinian residents are not of course Israeli. That said, documents are submitted into evidence, various experts testify and expert opinions are filed. The residents are represented by highly professional legal counsel. The parties follow the rules of civil procedure, and the judge makes his or her ruling based on the evidence before her or him, and on the interpretation of the law. There are indeed cases – not many – in which the courts ruled against the settlers who sought to challenge the protected tenancy of the residents, and recognized the validity of those rights.

In spite of all that, the drama unfolding in the courts is in large part a charade, a masquerade ball that hides, rather than reveals what is really happening and what the real issues are. This is not about the statute of limitations, or the payment of rent, or the straightforward recovery of property lost in war. It is about something much larger. Everyone in courtroom knows it, but as with a dirty family secret, it is spoken of only in hushed tones and behind closed doors.

The real issues raise a number of decisive questions, which may best be described as meta-legal:

Is it legal for the Government of Israel, its ministries, organs and official bodies and autonomous officials to harness all of the laws, regulations, procedures, and mechanisms towards the goal of transforming an existing Palestinian community into a settlement exclusively housing ideologically motivated settlers?

Is it legal for the Government of Israel, in its entirety, to always identify the public interest as identical with the interest of the settlers, and never that of the Palestinians? Is it legal for the ideological DNA of the settlers of East Jerusalem to drive the policies of the state of Israel, and the way it interprets its laws?

In one city, in which there was one war, in which some of the city’s two peoples were displaced and in which both peoples lost property, is it legal for the law to empower one people to recover the property lost in that war, while the other people is not entitled to do so?

Is it legitimate for Israel to advance its geopolitical goals in Jerusalem by means of large-scale displacement? Is it legal for Israel to systematically engage in actions that aim to take a neighborhood and its communities from its Palestinian residents, and to replace these neighborhoods with settlers?

When these or very similar questions were asked by the Klugman Committee in 1992, the resounding answer was “no, it is not legal”. It is possible, that the courts will rule similarly. For reasons detailed below, we consider such a ruling unlikely.

5.The Way Forward

In May 2021, convulsive violence gripped Israel, East Jerusalem and Gaza, and, as of this writing, have started to spread to the occupied West Bank. Two Jerusalem issues were major contributory factors in triggering the eruption of violence: events surrounding the Temple Mt./Haram al Sharif and the approaching displacement of the Palestinian residents of Sheikh Jarrah.

It is by no means a coincidence that these were the issues sparking violence. Among all of the issues that make up the Israel-Palestine conflict, two stand out as being exponentially more sensitive and volatile: Jerusalem and displacement. Both of these cut to the core of the national identities of both peoples. Both peoples define themselves by their devotion to Jerusalem, and both are haunted by a traumatic refugee past. The events of May 2021 took these two “radioactive” issues and transformed them into nuclear fusion, sparking the violence.

Neither the status of Jerusalem’s holy sites nor the question of displacement will disappear from the agenda of Israelis, Palestinians and the international community. They need be addressed.

In 1924, at the onset of the British Mandate in Palestine, the King issued the Palestine (Holy Places) Order in Council, 1924. The British very wisely concluded that the matters relating to Holy Sites and inter-religious disputes are so complex, intractable and volatile that they should not be adjudicated by a court of law. The Order states that “…no cause or matter in connection with the Holy Places or religious buildings or sites in Palestine or the rights and claims relating to the different religious communities in Palestine shall be heard or determined by any Court in Palestine“.

The Order in Council remains in effect, under Israeli law, until today. It may be argued that few documents, if any, have contributed more to the stability of the Holy Land, and prevented more bloodshed.

This approach has an antecedent in the Jewish tradition:

דאמר רבי יוחנן: לא חרבה ירושלים אלא על שדנו בה דין תורה

א“ע ל מציעא בבא “Rabbi Yohanan said: Jerusalem was only destroyed because the city adjudicated cases in accordance with the Laws of the Torah.”

Bava Metzia 30a

The Order in Council and the Rabbi Yohanan’s adage share an insight whereby there are matters so sensitive and of such cardinal importance that they are best decided outside the letter of the law, and outside a court of law.

The questions relating to the fate of the Palestinian communities of Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan constitute precisely such an issue.

It is quite possible, perhaps likely, that the Israeli courts will ignore the broad context of the suits regarding Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan, and rule as though this is indeed a “real estate dispute”. However, it is also possible that the court will address the meta-legal issues raised above. To do so the courts will be required to display enormous courage, and a willingness to embroil itself in one of the most hotly contended issues in Israeli society. Courts of law very understandably avoid entering the minefield of political controversy. Just as the United States courts refrained from ruling on the legality of the Vietnam War, the Israeli courts will very understandably tend to avoid ruling on the basis of the broader issues raised above, regardless of their merit.

As with the issues surrounding holy sites, the fate of the Palestinians families in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan should not be determined by a court of law. Removing these cases from the court docket will be doing a great service not only to the court, but to the peoples of Jerusalem, Palestine and Israel. Imposing upon the courts the obligation to rule on this matter is both unwise and potentially dangerous.

It is amply clear to all but the ideologically devout that the displacement of Palestinian families and Palestinian communities is not only a gross injustice, it is contrary to the genuine interests of both Israelis and Palestinians. It is also an issue so incendiary that it poses a threat to regional and global security.

The government of Israel has ample authorities to create circumstances that will leave the Palestinian families securely in their homes, and it would be well advised to do so.