What Happened? The Jerusalem Municipality’s Motion

- On February 26, 2021, the legal counsel for the Jerusalem Municipality filed a motion to the Jerusalem Local Affairs Court requesting that the Court rescinds the stay of execution of demolition orders that had until now prevented the demolition of tens of homes in al-Bustan area of Silwan.

- This motion was no routine event as it reverses a three years-old arrangement between the municipality and the residents. Indeed, since 2017, the Municipality has been adhering to a formal, albeit unwritten understanding, according to which the residents would pursue a planning process with the authorities, during which time all demolitions would be suspended.

What are the Immediate Ramifications of the Motion?

Because this motion is a sudden reversal of the Municipality’s position and of the 2017 understanding, it gave rise to speculations that the Municipality decided to move forward imminently mass demolition of tens, perhaps hundreds of homes in al-Bustan.

Yet, the significance of the municipality’s decision is not entirely clear as it seems that the situation is neither as dire nor as acute as it appeared when the motion was issued:

- Firstly, on March 17, the Court rejected the Municipality’s motion, and granted another stay of execution until August 15. In addition, if, in August, the Court will grant no further stay of execution, the residents will no doubt appeal to the Jerusalem District Court, further deferring possible demolitions for several months.

- Secondly, the motion filed by the municipality to the Court is, so far, the sole indication of a change in policy by the Municipality. Significant policy shifts of such magnitude are usually accompanied by other bureaucratic indications, by senior officials’ announcements , and with much fanfare from the settlers. We have noted none of these. SOMETHING of significance clearly happened with the reversal of Municipal policy regarding the 2017 understanding – but it’s not at all clear WHAT happened.

Israeli Planning Policies in al-Bustan

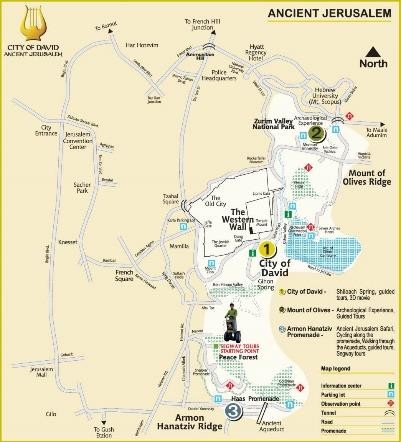

- Location – Al-Bustan is a wedge-shaped area, 38 dunams in sized, located in the bed of the wadi known in Arabic as Wadi al Joz (for the northern segment) and Wadi Na’ar (in the south) and in Hebrew as the Kidron Valley. The al-Bustan segment of the wadi is identified in Hebrew as Kings’ Valley, due to its proximity to the ancient monumental tombs to its north, and its proximity to the biblical city of David.

- Statutory status – Wedged between Wadi Hilweh on the west, and Batan al Hawa in the east, there were a number of Palestinian dwellings already standing in 1967. However, most of the construction in al-Bustan commenced after 1967. Generally speaking, Israeli planning policies were geared to put an artificial cap on Palestinian development and population growth. With building permits

largely inaccessible, today more than 50% of the homes in East Jerusalem were built without permits. This is especially the case in the area surrounding the Old City. The statutory town plan for this area, AM/9, allows for no construction of residential units.

Consequently, with the exception of those handful of houses standing in 1967, the hundreds of homes built in al-Bustan were built without permits, and by people who had no option to build legally.

- What makes the case of al-Bustan unique? – While al-Bustan is not unique in the fact that most of the construction is illegal (that applies to most East Jerusalem neighborhoods), al-Bustan is unique in that it is the sole neighborhood in East Jerusalem that has been targeted for large-scale demolition, and has been so targeted for more than fifteen years.

How Many Homes are at Risk of Demolition in al-Bustan?

- There are approximately 86 demolition files related to al-Bustan currently standing before the Jerusalem Local Affairs Court.

- Only a small number of these cases are still pending, and virtually all of them are after a verdict was handed down, a verdict that invariably includes a demolition order. This means that were it not for the stay of execution, these demolitions could take place at any time. There is no statute of limitation, and their validity never expires.

- Many of these files seek to demolish a building that is composed of more than one household or residential unit. A recent onsite survey revealed that while there are only 86 demolition orders, the number of homes at risk is in reality 130 households/residential units.

- Of the 86 demolition files, the verdicts in 14 cases were handed down after October 2017, the date on which new Israeli legislation significantly limited the authority of the Court to issue stays of execution of demolition orders. Consequently, these demolitions orders have not been stayed. That means that in these cases the demolitions can take place at any time, with little or no warning.

However, to date, there is no indication that these 14 homes are being actively targeted by the authorities, and do not now appear to be treated differently from the tens of thousands of homes in East Jerusalem which are subject to outstanding demolition orders that can be executed at any time.

- As noted, in 2017, the Municipality agreed to suspend demolitions while the residents pursue the approval of a statutory Town Plan. The residents’ Town Plan is being drafted by Dr. Yusuf Jabarin, the Dean of Research at Haifa’s prestigious Technion Institute. The plan is working its way slowly through committee, and it is common that plans of this complexity take many years to approve. The plan is based on 11 principles to which the Municipality and the residents both agreed in 2017, and aspires to balance between the housing needs of the residents, the legitimate need for public spaces, in a manner that will serve the residents of al-Bustan, and not the settlers of Silwan. Initially the Municipality viewed the Plan favorably, but, in recent months, that support appears to have been withdrawn.

We will now examine why, of all of East Jerusalem’s neighborhoods, Silwan has been targeted.

The Background to the Bustan Demolitions

- The predominant role of Elad – Since 1991, Silwan/the City of David has been the flagship of the Elad settler organization and of the biblically motivated settlements in East Jerusalem.

Elad is the most powerful settler organization in Israel and the West Bank. Initially, its goal was simply to transform Silwan into an extension of the Jewish Quarter, but over time their ambitions grew. The goal of Elad became and remains the creation of a renewed biblical realm in the visual basin of the Old City, with the physical manifestation of a Jewish Biblical past, genuine or recreated, embedded in the landscape. This is to be achieved not only by means of settlements, but by a series of parks, excavations and attractions, linked by trails, guaranteeing that the visual elements in the historic basin of the Old City will evoke memories of ancient Biblical Jerusalem.

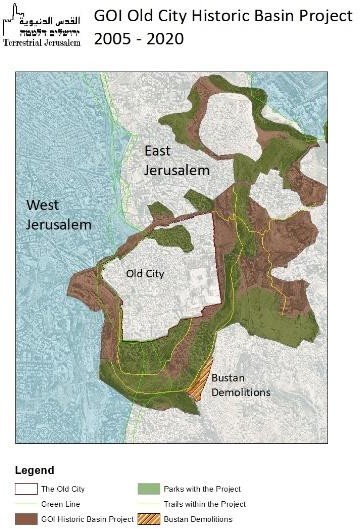

- An agenda formally endorsed by the government – On August 9, 2005, Elad’s ambitions became the official policy of the Israeli Government. Ariel Sharon’s government approved an ambitious multi-year plan to radically transform the area around the Old City, the goal of which is :

“…to strengthen the status of Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Israel and to allocate 50 million shekels in each of the budgetary years 2006-2013 for the restoration, development and maintenance of the basin of the Old City and the Mount of Olives…Activities will be carried out by means of the Jerusalem Development Authority

[“JDA”], which will… report on its activities and tasks to the Director Generals of the PM’s Office and the Jerusalem Municipality and the Head of Budget at the Ministry of Finance. [JDA] …will be assisted by sub-contractors”.

This plan is periodically refunded and has remained the blueprint for Israeli development schemes around the Old City. In essence, the DNA of Elad’s biblical ideology became the DNA of the Government of Israel in and around the Old City, with Government outsourcing many of its authorities to Elad in order to pursue these objectives. The lines between government and the settlers became so blurred that they almost disappeared.

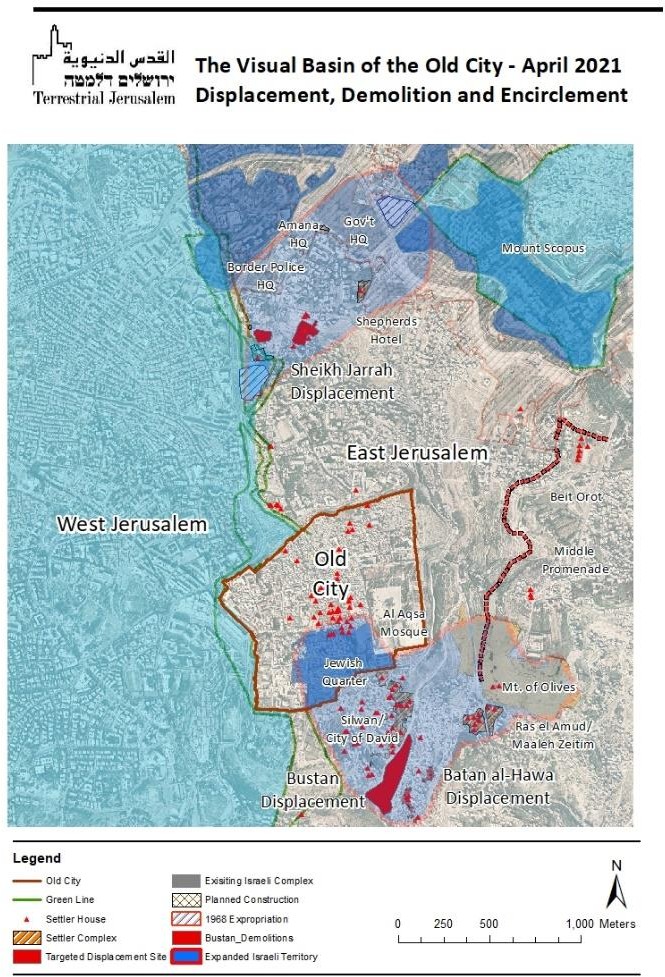

- Why al-Bustan has been specifically targeted by Elad? A comparison of these two maps, the one produced by Elad and disclosing the nature of their ambitions in the historic basin of the Old City, and the other of the official boundaries of the Governmental Historic Basin Project, not only disclose how similar they are in their geography and their objectives – they also disclose just why al-Bustan has been targeted.

Al-Bustan is a target because more than any other Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem, it is an obstacle standing in the way of one of the most important settler/government projects anywhere in East Jerusalem and the West Bank: the so- called restoration of purportedly biblical Jerusalem through genuine artifacts, invented facsimiles, and attractions reminiscent of the pseudo-biblical theme park. Al-Bustan is right in the middle of it.

Chronology of the repeated attempts to demolish al-Bustan

- The idea of demolishing the entire al-Bustan area emerged in the mid 2000s, hand in hand with the scheme to transform the visual basin of the Old City into a biblically driven landscape.

- In 2005, the Jerusalem Municipal Council adopted a resolution calling for the demolition of 88 houses in al-Bustan. The number 88 has ever since been attributed to the number of homes in al-Bustan, regardless of its accuracy. To this day, one frequently hears of the plan to demolish 88 houses. The international uproar that ensued was so fierce that Mayor Lupolianski was compelled to withdraw the plan.

- In 2009, newly elected Mayor Nir Barkat, who was and remains closely associated with the settlers in Silwan, revived the project. He too encountered strong opposition to the demolition of 88 homes, so in 2010, the Municipality tried to mute that opposition by reducing the number to 22 demolitions. That too did not work. The opposition to the demolitions were as vehement as they were with Lupolianski (even being cited prominently in the State Department Annual Human Rights Report of 2010). Ultimately, Barkat was compelled to back down as well.

- Since 2010, there were a couple of attempts to create town plans for al-Bustan and its residents, which culminated in the current Jabarin Plan.

- In September 2017, the Municipality concluded an 11-point document with the agreed planning principles, which underlies the current plan that is before the planning boards.

- For three years, the Municipality viewed the emerging plan as sufficient cause to suspend demolitions, and so notified the Court. However, on February 23, 2021, counsel for the Municipality notified the Court that “the attempt to change the Town Plan at the site in question is at its embryonic stages in spite of the extensions granted to date, there has been no significant progress, and there is no way of knowing which buildings may be legalized by it…”.

What Happens Next?

- No immediate plans to demolish – Based on our cumulative experience, and familiarity with the parties involved and how they have acted to date in similar situations in the past, the mass demolition of al-Bustan does not seems to be imminent.

- Vigilant monitoring required – Currently, there is little to be done except vigilant monitoring and extending moral and material support to the residents, their lawyers and town planner (all of whom are highly professional) to obtain the approval of a statutory town plan, delay demolition, and await developments.

- Signaling concern to Israeli authorities – Should there be an opportunity to express deep concern over possible developments in al-Bustan to Governmental and Municipal authorities, that indeed should be exploited. However, the current situation does not

appear to create ample cause to justify intense, focused and resolute engagement by the international community– yet.

- Limited prospects that a statutory town plan will be approved – Stays of execution by the Court are likely to be cyclically repeated, ad infinitum. However, the chances of any plan submitted by the residents being approved by governmental or municipal authorities are remote to non-existent, however professionally sound it might be. Al- Bustan is “Kings Garden” to the settlers of Elad, and their most highly coveted piece of real estate in the heart of their biblical realm. They are the most powerful settler movement with an open door to the Prime Ministers, and whose functionaries are now in key positions of authority in matters relating to the planning of Silwan. Bluntly, the residents do not stand a chance.

Sadly, the goal of the planning process is to defer the demolitions, not to create the statutory framework that will allow to address the genuine housing needs of the residents of al-Bustan.

A Final Important Caveat: the Rules of Engagement are Changing

- Largescale displacement is no longer a taboo – Our analysis above leads to cautious and tentative conclusions indicating that the Bustan demolitions, as abhorrent as they are, have not yet become an acute issue. An important caveat is to be added to this conclusion: over the last few years, the government of Israel has started deviating from policies of restraint that have been a constant since 1967, and is engaging in actions that would have been unthinkable a few years ago. The demolition of al-Bustan is highly compatible into these new policies.

Since 1967, Israel was able to transfer 220,000 of its residents to the settlement neighborhoods of East Jerusalem without the largescale displacement of Palestinians.

The last such largescale displacement took place on the night of June 10, 1967, when the Mughrabi Quarter was razed, and its residents expelled. Nothing remotely similar has taken place in East Jerusalem since then. This, by no means, is meant to detract from the devastating impact the settlement enterprise has had on individual families that have been targeted and displaced by settlers, and the impact this has had on entire Palestinian collective in East Jerusalem.

However, the policy of refraining from large-scale displacement has recently changed, and is no longer a taboo.

- A shift targeting two

separate locations: the visual basin of the Old City, the very epicenter of the conflict, Israel is for the first time actively engaged in attempts to displace two entire communities – Batan al Hawa in Silwan and in Sheikh Jarrah – so they may be turned into settlement blocs. The mass demolition of al-Bustan, as it seeks to displace an entire community to enhance the contiguity between Israel and settlements enclave, is part of the same policy shift. While, in the past, there were occasions on which the government was complicit in targeting individual families for the benefit of the settlers, this is the first time since 1967 that entire neighborhoods are being targeted.

Geopolitical Ramifications on the Two-State Solution

- The creation of contiguity between settlements enclaves – The staggering humanitarian implications of mass demolitions in these areas are accompanied by compelling geopolitical ramifications. For the first time since 1967, settlement enclaves that were dis-contiguous with Israel are now becoming extensions of pre-67 Israel, and in a pincer movement: the Old City is being surrounded both on the north and the south by built up Israeli areas.

- The Faith Dimension of these policies – The geographical changes are radically challenging the possibility of future political agreement, and the nature of these endeavors threaten to morph a resolvable political conflict into a zero-sum religious conflict. The mix of a humanitarian melt-down, the radical geographical changes impacting of future possible agreements, and the inflammation of the faith dimension of the conflict create a dangerous mix indeed.

- The need to closely monitor the situation – It is important to bear these developments in mind as we observe what is happening in al-Bustan. We have stated, based on past experience that there is no clear indication that a decision has been made to imminently pursue the demolition of al-Bustan. We stand by that conclusion.

Yet, mass demolition in al-Bustan would enable another link in the ring surrounding the Old City on the south. This is why ,although there may be no immediate plans to demolish, the developments in al-Bustan should be monitored very closely as the broader context of the municipality’s motion and the powers involved indicate that the final word has likely not been said.

This important caveat is worthy of a “stand-alone” in-depth analysis of its own, which we plan to release in one of our upcoming reports