MUSLIM PILGRIMAGE TO HARAM AL SHARIF/THE TEMPLE MOUNT:

TINKERING WITH EXPLOSIVES

In recent days, the first visit to Al Aqsa Mosque by Muslim pilgrims after the Israel-UAE and Israel-Bahrain normalization agreements took place. The visit by a group of businessmen and women from the United Arab Emirates has exposed the dynamics of a potentially explosive situation evolving on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif. The approaching large-scale Muslim pilgrimage under the auspices of normalized relation between Israel and Arab states is not a routine event and raises the prospects of violent confrontations between Muslim and Muslim on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif in the near future.

This analysis seeks to explore the ramifications of these developments, and to assure they receive the attention they deserve.

- Background: The Israeli-UAE normalization agreement and the Status Quo

- An initial failed attempt to change the status quo – As explained in detail in our previous editions, the wording of the August 13 US-UAE-Israeli Joint Statement, which provides that “… all Muslims …may visit and pray at the Al Aqsa Mosque“, while “…Jerusalem’s other holy sites should remain open for worshipers of all faiths“, opened dangerously the door for an unequivocal, albeit camouflaged, change in the status quo. According to this provision, Jewish prayer is to be forbidden only within the structure of the mosque but, in violation of the current status quo, will be permitted in the other areas of the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif.

The United States and Israel encountered serious opposition from stakeholders in the Arab world. Hence, after intense, discrete diplomacy, it was decided to remove all reference to Jerusalem and its holy sites from the binding bilateral agreements between Israel, the UAE and Bahrain, respectively, and a looming crisis was averted (see our last report for a description of this development).

- Were there secret understandings with the UAE in regard to the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif? – Members of Knesset, Israeli activists and scholars have in recent days been claiming that there are secret annexes to the Israel-UAE agreement that relate to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif. There is a consensus among those reporting on these secret understandings that, to their disappointment, they aim at reaffirming the status quo and the prohibition against Jewish prayer, rather than altering it:

- In the run-up to the ratification of the UAE agreement, MK Bezalel Smotrich wrote to the Prime Minister:

“In order to stand for the Israeli-Jewish interest at the holiest site in the world for Jews, I ask to receive all of the agreements between the sides, written or oral, connected to the Temple Mount, its diplomatic and property status, its administration and visitation and prayer arrangements for Jews and for those who are not”.

- Journalist and scholar Pinhas Inbari of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs went even further (JCPOA is a right-wing think-tank headed by Amb. Dore Gold, Netanyahu’s past ambassador to the UN, and who have been repeatedly reported as not only advising Netanyahu on the Trump Plan, but having taken an active part in crafting the Jerusalem component of the Plan). In an October 16 interview to A Hura, Inbari stated:

“…asked if there were any secret clauses to the agreement I replied that I think there are, but they relate not to F35s but to the stability of the Temple Mount…without stabilizing the situation on the Temple Mount in cast iron, the Saudis will not formally enter the process…When asked why the clause was being kept a secret, I replied that he doesn’t want the settlers and Bennett to know about it, and the Emiratis are attentive to Netanyahu’s electoral considerations”.

There are no conclusive evidences to date that enable us to corroborate the existence of such understandings. But whether they exist or not, the disappointment expressed by those who seek to end the current status quo by allowing Jewish prayer on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif confirms what was and remains their respective expectations.

- The visit of the UAE’s delegation – Even though the attempt to change the status quo in the context of the Israeli-UAE agreement was ultimately neutralized, we cautioned in our last edition of Insiders’ Jerusalem that these efforts would not abated and were expected to intensify. Unfortunately, these suspicions proved to be correct even sooner than expected. On October 15, a group of Emirati citizens fulfilled the promise that Muslims from around the world would be able to pray on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif. The problem is that it did so without coordinating with the Jordanians, the Palestinians nor the Waqf and while being accompanied by the Israeli police. The way in which this visit took place should raise concerns regarding the potential implications of largescale Muslim pilgrimage to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif under the circumstances created by normalization.

- The Waqf, the Status Quo and Access to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif

The question of who may access the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, who decides who may enter, at what times, and from where, are all parts of the complexities of the status quo. This is complicated by the fact that over time, there have been certain changes in the manner in which the status quo was implemented (for a comprehensive analysis of the status quo, see here). Regardless, and for the sake of clarity, we will attempt to simplify the description of these arrangements without creating a distorted view of the reality on the ground.

- Background

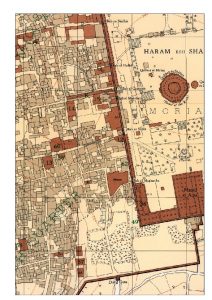

- The taking of the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif – On the third day of the 1967 war, June 7th, 1967, Israeli paratroopers captured the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif – home to the remains of the ancient Jewish Temple and, since 705 AD, home to the third holiest site in Islam, the al Aqsa Mosque. Arriving on the scene hours after the paratroopers did, legendary Defense Minister Moshe Dayan saw Israeli flags flying over the esplanade, planted there by IDF soldiers. Without hesitation, Dayan ordered the flags removed. Reportedly, he told those around him: “Take those down and don’t put them up again. We don’t need a holy war.”

Dayan’s order reflected his visceral understanding of the implications of Israeli control of the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif and the imperative of balancing Israeli national claims with Muslim religious sensitivities.

- The keys to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif – Based on this understanding, de facto authority over the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif was to a large degree to remain with the Islamic authorities (the Muslim endowment known as the waqf), with whom Dayan left the keys to the ten existing gates to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif. However, a significant change to this arrangement took place in August 1967, and has remained in effect to this very day. After access to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif was denied to visiting IDF soldiers, Dayan confiscated the keys to one of the ten gates, the Mughrabi Gate, located above the Western Wall plaza.

- The Mughrabi Gate and the Mughrabi Quarter – The Mughrabi Quarter was established in 1193, shortly after Saladin’s conquest of Jerusalem, and settled by Moroccans, made up of a mixture of North Africans and Andalusian Muslims. The Mughrabi Gate was located at the southeast corner of the Quarter. On the northern perimeter of the quarter, adjacent to the containment wall of the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, was the Western Wall. As a physical remnant of the wall surrounding the Temple Mount, it had become a highly important focus of Jewish devotion and site of prayer. The area in front of the Western Wall was no more than an alley, 28 meters long and 3.6 meters wide. Both the Wall and the area adjacent to it were owned by the waqf. Prayer times, and the religious ritual items allowed at the site, were limited, and hotly contested. The fact that the site was located in an active Palestinian neighborhood exacerbated these tensions.

- The demolition of the Mughrabi quarter – On the night between June 10 and 11, 1967, only hours after the ceasefire in the 1967 war went into effect, Israel brought earth moving equipment into the Old City and razed 135 homes in the Mughrabi Quarter.The demolitions were completed by dawn, with one Palestinian fatality and hundreds driven from their homes. In the ensuing two years, more than an additional 100 homes in the Mughrabi Quarter were demolished.

- The Western Wall Plaza – The razing of the Mughrabi Quarter created the monumental Western Wall Plaza as we know it today. The demolitions were motivated by both symbolic and practical considerations. Firstly, the creation of the plaza was meant to redress the injustice and humiliations felt by Jewish worshipers during the Ottoman and British Mandate Periods. More importantly, the ceasefire took place a few days before the pilgrimage festival of Shavuot, and the authorities wanted to be able to accommodate the throngs expected to attend prayers. By morning, the plaza was 20,000 sq. m. in size, and able to hold hundreds of thousands of worshipers. There was never an attempt to justify the legality of the razing of the Mughrabi Quarter, and it is perceived by the Palestinians of East Jerusalem as the site of a war crime.

- The Gates: Access to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif

There are currently ten active gates to the esplanade of the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, and it is important to distinguish between the Mughrabi Gate and the other nine:

- Who control the nine gates? – Formally, the control of the nine gates is vested in guards employed by the waqf. They are posted at each gate, immediately inside the perimeter of the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, granting or denying access. As a matter of longstanding policy, non-Muslims are denied access through these gates.

- Who controls the perimeter? – The security perimeter around the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif is a double perimeter. Israeli Border Police guards are posted a meter away from the waqf guards, just outside the boundaries of the esplanade. The actions of the Israeli guards range from a cursory inspection of the individuals seeking to enter the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, to a total lockdown of the site. For example, it is not uncommon for the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif to be closed on Fridays to men below the age of 45, or for individuals to be turned away or detained, all enforced out by the Border Police.

- The dilution of the Waqf’s authority – The apparent “autonomy” of the waqf is deceptive. Israeli police do enter the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, and under various circumstances. Small periodic patrols take place on the esplanade, as another symbolic expression of the Israeli sovereignty on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif to which Israel lays claim. Invariably, the police accompany the Temple Mount activists entering the esplanade, often preventing skirmishing between Temple Mount activists and Muslim worshipers. In the past, the police had a reputation for fairhandedness, having a moderating influence on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif. In recent years, and clearly inspired by the Israeli government, the police are in now league with the Temple Mount activists, at times enforcing the prayer ban, but at other times doing their bidding. In extremis, when there are largescale protests and disturbances on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, large numbers of riot police are deployed, clashing with the protestors.

- Existing arrangements at the Mughrabi gate – As noted, the arrangements at the Mughrabi Gate are entirely different, since it is the only gate under “direct” Israeli control and through which non-Muslims may visit the site (until the mid-19th century the Ottomans denied entry to non-Muslims). Since 1967, Israel has had sole control over this gate, even if there is a waqf guard symbolically posted nearby. As a rule, the gate is open to visitors from 07:30 until 11:00, and again from 12:30 until 1:30, Sunday-Thursday.

- Coordination arrangements pre-2000 – These features of the status quo are not immutable. Prior to the outbreak of the second intifada in 2000, the waqf guards posted at the Mughrabi Gate also had a say on who may or may not enter the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif. In 2000, the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif was shut down for the first three years of the second intifada, and when it reopened in 2003, Israel no longer recognized the role of the waqf guards in deciding who may or may not enter. This issue has been a major point of contention in the attempt to restore Israel-Palestine relations to the pre-2000 status quo ante.

- The role of Israeli security at the Mughrabi gate – The tasks of the police posted at Mughrabi Gate is not only subjecting each visitor a security check, but weeding out potential provocateurs. The Commander of the Temple Mount during the 1980s has reportedly stated that under his watch no visitor who advocated changing the status quo was allowed to enter the Mount. That is far from the case today. Few of the 35,000 visitors to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif are Israelis visiting for the first time. Many are repeated visits by Temple Mount activists who demonstrably display and articulate on site their intentions to change the status quo. Several years ago, an Israeli Minister of Construction went to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif to pray (against the policies of his own government), posting a clip on youtube in which he expressed his hope for the construction of the Temple during his tenure in office – indicating just how much the Temple Mount movement’s demand to change the status quo has gone mainstream.

- The rise in the numbers of Jewish visitors – The numbers of Jewish visitors have soared in recent years, so much so that it has had a qualitative impact on the character of the site. For example, in 2010 there were about 5,700 Jewish visitors annually, in 2016 the numbers rose to 14,000, and to more than 35,000 in 2019.

- Are Muslims allowed access through Mughrabi Ramp? Yes – unless they’re Palestinians. Pilgrims from Morocco to Indonesia are allowed to enter, but Palestinians are not. They are not even allowed to enter or traverse the monumental Western Wall plaza adjacent to the gate. While all visitors are routinely given security checks at the entrance to the plaza or at the Mughrabi Gate, Palestinians are systematically turned back. Apparently, no security check is effective enough to allow the presence of a Palestinian. The inability to traverse the plaza treble or quadruple the walking distances of routine routes needed by the Palestinians.

There are a number of exceptions to this rule, and it has produced one of the most surrealistic manifestations of Israeli rule in East Jerusalem: “The Pedestrian Permit”, which grants a small number of elderly or disabled Palestinians who reside nearby, mostly in Silwan, access to the plaza.

- Muslim Pilgrimage to Al Aqsa Mosque

- The Trump Plan – The right of Muslims from around the world to visit and pray at Al Aqsa has been one of the centerpieces of the Trump plan and the normalization process. Trump himself said at the September 15 White House signing ceremony of the normalization agreements:

“The Abraham Accords also open the door for Muslims around the world to visit the historic sites in Israel and to peacefully pray at Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, the third holiest site in Islam”.

Citing Muslim pilgrimage to Jerusalem as one of the major achievements of the Trump administration, Presidential envoy Jared Kushner recently “highlighted the inclusion of clauses in both agreements, as well as in the Trump peace plan, that affirm Israel’s commitment to allow all Muslims to visit and pray at Jerusalem’s al-Aqsa Mosque”.

- Israel’s attitude towards Muslim pilgrimage prior the Trump plan – However much an achievement or not, Muslim pilgrimage to Al Aqsa is not new. Israel has for many years been openly encouraging Muslim pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and succeeding. In recent years (and until the outbreak of Covid 19) there have been tens, at times hundreds of thousands of Muslim visitors annually to Al Aqsa, with almost half of whom coming from countries with no diplomatic relations with Israel. Even then, Israel viewed these visits as a harbinger of normalization with the Arab and Muslim worlds.

- The ramifications of the normalization agreement – The new provisions of the normalization agreement between the UAE and Israel regarding Muslim pilgrimage indeed constitute a fundamental change in the nature of the pilgrimage. While it was in the past possible for Muslims from Indonesia to Morocco to obtain entry visas, this is a cumbersome, and at times daunting process. Pilgrimage of UAE’s citizens will now be streamlined, and there can be little doubt that the mutual waiver of visa requirements made by Israel and the UAE was motivated in no small part by considerations geared to promote large scale Muslim tourism from UAE to Jerusalem.

Secondly, Muslim pilgrims have entered and prayed on Haram al Sharif under the auspices of the waqf, the visitors from the UAE will enter accompanied by the Israeli police.

- The PA’s position towards Muslim pilgrimage to Al Aqsa – If, in the past the Palestinian Authority not only approved of but encouraged Muslims to pray on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, the provisions of the Israeli-Emirati agreement regarding pilgrimage to Jerusalem have led them to reverse this position. The Palestinian Authority and the waqf now oppose the Emirati and Bahraini visits, as part and parcel of their opposition to normalization in general.

- A theological and political debate in the Muslim world – The question of the legitimacy of visiting Al Aqsa while it is under Israeli occupation has, in recent years, generated one of the most heatedly debated theological disputes in the contemporary Muslim world, and one with far-reaching political ramifications.

One of the most influential Muslim theologians (especially among political Islam) is Qatar-based Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi. Al-Qardawi issued a fatwa ruling that “…Muslims should not visit Jerusalem because it requires dealing with Zionist embassies to obtain visas…Such visits might also give legitimacy to the occupation and could be seen as normalization”.

The response was not late in coming. On April 18, 2012, the Grand Mufti of Egypt, Sheikh Ali Gomaa, accompanied by the senior member of the Jordanian royal family responsible for Jerusalem issues, HRH Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad, together paid a high profile visit to Haram al Sharif and prayed at Al Aqsa. Mohammad Hussein, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and Palestine, issued a fatwa approving the pilgrimages, and PA President Abbas “…called on Muslims everywhere to visit Al-Aqsa and revitalize it by filling it with worshippers and pilgrims.” On the other hand Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood (most notably the Jordanian Islamic action front), strongly criticized the visit, stating it was “a blow to the national struggle which succeeded in thwarting all attempts at normalization throughout the past years.”

The heated controversy that ensued eventually died down, but never disappeared. It has been ignited anew by the normalization agreements.

On August 18, 2020, days after the announcement of the normalization agreement, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and Palestine, Sheikh Muhammad Hussein, issued a fatwa ruling that Muslims who normalize relations with Israel, such as the Emiratis, are banned from visiting Al-Aqsa:

“I stress that praying at the Al-Aqsa mosque is permitted to everyone who enters [Palestine] in the legal Palestinian manner or [is granted access] by the government of our sister [country] Jordan, which is the custodian of the Islamic holy sites in Jerusalem, but not to those who normalize relations [with Israel] and use this to cooperate with the criminal ‘Deal of the Century.’ Normalization [with Israel] is one of the manifestations of this deal, and anything that follows from this deal is forbidden, and is null and void according to the shari’a, for it is aimed at abandoning Jerusalem”.

In short order, this fatwa was rejected by other prominent Muslim clerics. Former Deputy Sheikh of al Azhar Abbas Shuman ruled that while he is not ruling on the Emirati decision to sponsor this pilgrimage, this is not a matter to be adjudicated by Sharia law, and should be left to the politicians.

- What Just Happened? The October 15 Emirati Visit to Al Aqsa

On Thursday evening, October 15, the first delegation of visitors arriving under the newly signed normalization agreement visited Haram al Sharif/the Temple Mount. The news spread quickly in Palestinian social media and beyond. Initially, there were rumors that the delegation was from Oman, compelling the Kingdom of Oman to issue a formal denial.

Ultimately, it turned out that the group of approximately ten businessmen and women were from a major agricultural company in the UAE. The objective of their visit was to meet with the Israeli irrigation technology firm, Netafim. The pilgrimage was not the purpose of the visit itself, but integrated into the itinerary of their business trip. Accompanied by Israeli officials and security, the delegation gathered in the Western Wall Plaza, adjacent to the Mughrabi Gate.

It was widely reported that the delegation had entered the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif via the Mughrabi Gate and Palestinian Prime Minister issued a statement asserting “One ought to enter the gates of the blessed Al-Aqsa Mosque by way of its owners, rather than through the gates of the occupation”. However in reality, the delegation entered Bab as-Silsileh (the Chain Gate), not the Mughrabi Gate.

Unlike the arrangements at Mughrabi Gate, under the responsibility for monitoring the entrance to Bab as-Silsileh is vested in the waqf guards posted there. However, the visit had not been coordinated with the waqf, the Palestinians or the Jordanians. Instead, the delegation was escorted by Israeli police.

There was only a small presence of Palestinian worshipers on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif at the time. Lockdown regulations throughout Israel on that day forbade people from going more than one km. from their homes, and the police had limited access to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif only to the Muslim residents of the Old City. There were no Jewish worshipers at the time, since there were no visits by Jews to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif during the national lockdown. Upon entering the Al Aqsa Mosque, the members of the delegation were accosted by Palestinian worshipers who hurled insults at them and forced them to leave – similar to the “reception” that given a vocally pro-Israel Saudi blogger in July 2019.

The visit was widely covered in the domestic and international press, and generated anger in Palestine and throughout the Arab world. The Emiratis and other supporters of normalization countered with arguments in favor of the visits.

- The Impact of “Normalization” Visits: the Lessons so Far

While the recent Emirati visit to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif has all of the trappings of a minor incident, on closer inspection it portends the likely approach of a serious crisis. If, until today, there was constant concern over the potential of violent clashes on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif between Muslims and Jews, the approaching visits of large numbers of “normalization” pilgrims make the prospect of violence between Muslim and Muslim chillingly likely. Under current circumstances, it is difficult to see how these visits will go without incident.

In order to grasp the potential volatility of the situation, it is necessary to understand just how important Al Aqsa is to the Palestinians of East Jerusalem and the role that the Waqf plays in that respect.

- What is at stake for the Palestinians – There is no need to dwell on the significance of Al Aqsa for the devout Muslim, wherever he or she may be. However, for the Palestinians of East Jerusalem, its significance goes well beyond that. It is the one remaining “safe space” for Palestinians, where they need not fear the arbitrary humiliations of occupation. It is the place where, through the waqf, there is a measure of self-rule and control over one’s own life. The autonomy of the waqf and its authorities, coupled with Jordanian custodianship over the holy sites are powerful symbols of the Palestinian, Jordanian and Muslim dimensions of the city, which elsewhere is being so systematically expunged. While the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif may be one of the most sensitive sites in the world, it is also in many senses the least occupied space available to the Palestinians of East Jerusalem.

- A sense of autonomy provided by the Waqf – There are a number of revealing events that disclose just how jealously this Arab/Muslim character of Haram al Sharif/the Temple Mount has been protected. In 2014, Pope Francis visited the Holy Land, and among else visited Jerusalem’s holy sites. Israel insisted that the Pope ascend to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif via the Mughrabi Gate, and be accompanied by Israeli security. The waqf, the Palestinians and Jordanians all rejected these demands. The Holy See respected the autonomy of the waqf. The Holy father entered through one of the gates secured by the waqf, was accompanied by the waqf and not the police, and was received at Al Aqsa by Jordanian Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad, much to Israel’s consternation. Similar demands were made by Israel in the run-up to Prince William’s 2018 visit to Jerusalem. The British government rejected demands for the presence of Israeli security and ascent via the Mughrabi Gate, and this time Israel was angered when Prince William was received at Al Aqsa by a senior Jordanian diplomat.

- The ramifications of the UAE’s visit from the Palestinian perspective – The Emirati visitors not only failed to coordinate their visit with the waqf, the Jordanians and the Palestinians, their visit was secured not by Waqf guards but by Israeli security, the quintessential symbol of occupation for the Palestinians. From the Palestinian and Jordanian perspective, the Pope and the UK, both of which have full diplomatic relations with Israel, were far more attentive to and respectful of their equities and authorities on Haram al Sharif/the Temple Mount than the UAE. Unlike the messages made by the Papal and Royal visits, the Emirati delegation visited as guests of Israel, and not under the proprietary auspices of the waqf, the Palestinians and the Jordanians – an auspices almost universally recognized by the international community. These developments fuel some of the Palestinians’ deepest fears, whereby the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif will be transformed from a Muslim holy site into a “shared” Jewish-Muslim site, and recognized as such by the countries normalizing relations with Israel.

- Access and Freedom of worship for all, except the Palestinians – While one of the pillars of the Trump Plan is its provisions regarding universal access to holy sites in general, and in Jerusalem in particular, it overtly ignores the fact that Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza have little or no access to Jerusalem in general, and to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif in particular:

- The entry permits, when granted, generally apply on Friday only, and for individuals over the age of 45. It is easier for a Palestinian Muslim from the West Bank to pray at a mosque in London than it is at the Al Aqsa Mosque. No such limitations are imposed on the “normalization” pilgrims, and al Aqsa is far more accessible to them than to the residents of Abu Dis who live a mere four kilometers away. This took the most absurd turn on the day of the visit of the UAE’s delegation as Palestinians residing more than 1 km. away from the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif were denied access to Al Aqsa due to COVID19 restrictions, while Emirati pilgrims who live 2000 km. away were granted access. The Emirati visitors were also allowed to enter the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif from the Western Wall Plaza – a location from which Palestinians are permanently barred and which was raised on the site of the razed Mughrabi Quarter, which remains a fresh, open wound to the Palestinians of East Jerusalem.

- Access to Haram al Sharif/ the Temple Mount is virtually non-existent for the Palestinian residents of Gaza. There are only rare exceptions.

- Access to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif is often limited even for the residents of East Jerusalem, with young men and women often barred from Friday prayers due to “security concerns”. Restraining orders targeting activists (some of whom are indeed violent, and many of whom are not) forbid visits to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif for a certain period of time.

- Potential ramifications for Jordan – These developments are no doubt of special concern to the Jordanians. In the lengthy text of the Trump Plan, there is no mention of Jordanian custodianship over the holy sites, nor is there in any mention of Jordan in the statements and documents accompanying the normalization process with the UAE and Bahrain. Jordanian custodianship is conspicuous by its absence from these texts (at two press briefings, Jared Kushner did mention Jordanian custodianship, but in a manner that suggests that it’s “for now”). In addition, there have been numerous reports, the credibility of which is uncertain (most, if not all, having been issued by pro-government/right-wing sources), whereby Jordan custodianship on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif – rooted not only in history but in the Jordan-Israel Peace Agreement – will soon be replaced by a Saudi custodianship, as part of a package to entice the Saudis to normalize relations with Israel (others have suggested that the Jordanians would not be replaced, but that their role would be diluted). The manner in which the Emirati visitors simply ignored Jordan and the waqf, whose authorities have been universally respected by others, has amplified these concerns.

- Conclusions and Takeaways

- The Likelihood of Violence

- The specific circumstances of the recent visit of the UAE delegation – One should not be deceived by the relative calm with which the October 15 visit took place: the lockdown that reduced the number of Palestinians on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, the small number of participants in the Emirati delegation and the element of surprise were all conducive to this calm. It is not likely that subsequent visits to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif under the umbrella of normalization of Israel will proceed without incident.

- Why these visits may spark violence? – the significance of Al Aqsa and all it entails cut to the core of Palestinian identity, an identity that the Palestinians of East Jerusalem especially perceive as being under attack. These are not views held only by certain elites or sectors of Palestinian society. They are close to a consensus. It is precisely for this reason that the outbreak of convulsive violence in Jerusalem has almost invariably been related to a real or perceived threat to the integrity of Haram al Sharif: the disturbances following the 1909 Montague Parker excavations, the 1929 Palestinian uprising triggered by a dispute over prayer arrangements at the Western Wall, the outbreak of violence in 1996, in the wake of Netanyahu’s opening of the Western Wall tunnel, the 2000 Sharon visit to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, and more.

Therefore, it is very difficult to envisage a scenario in which there will be large numbers of Emirati and Bahraini visitors to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif in the manner we have described without there being frequent violent clashes between the Palestinian worshipers and the “normalization pilgrims”. The significance of Al Aqsa is so deeply embedded in the Palestinian psyche that no one will need organize the protest, and no one commands the authority to stop them.

- The risk of a uncontrolled escalation – If such clashes take place, the risk of escalation is real as it will trigger an inevitable Israeli response by police and the border police.

These clashes could lead the Israeli police to bar the Palestinians of East Jerusalem from the site in order to guarantee the security of visitors from the Gulf. No one would welcome such a development more that the Temple Mount Movement. Their dream – a temporal division of the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, which will be a Muslim site at certain times of day and a Jewish site at others – is the Palestinian nightmare. Hours in which Palestinian worshipers are denied access to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif would make that goal all the more achievable.

- Is such an escalation avoidable? Can Emiratis and Bahrainis visit Al Aqsa without the fear of violence? Yes – but only if their visits are fully coordinated with the waqf, something that appears to be impossible under current circumstances. Israel will never allow it, and the Palestinians will accept nothing less.

- The Immediate Takeaways

- The need for a discreet engagement of relevant stakeholders – There are clear indications that Israel and the Emirates are prioritizing these visits to Al Aqsa. Jerusalem’s deputy mayor recently stated that “… “Jerusalem will host between 100,000 and 250,000 Muslim tourists a year; they dream of visiting Al-Aqsa”. The mutual waiver of visas by Israel and the UAE, the fact that an Emirati delegation was admitted to Israel without quarantine, while access is being denied to other foreign visitors indicate the level of resolve.

Even if none of the relevant stakeholders are inclined to seek an accommodation, it is imperative to explore the possibilities of defusing this situation, even temporarily. Urging restraint under these circumstances may seem to be a meek appeal inadequate to the challenges, but remains essential.

As long as the United States does not try to mediate between these conflicting positions, the countries in the region who are trusted by all parties and who managed through discreet and intensive engagement to defuse the risk of a change of the status quo in the normalization agreements could here also prove efficient in delivering a positive compromise.

- Reaffirming the status quo. The special historic role of Jordan in relation to the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, as enshrined in the Israeli-Jordanian Peace Agreement should be reaffirmed by the international community as a key component of the stability of the status quo. There is also a need to elicit from Israel, the Palestinians and the Jordanians a recommitment to the status quo, the Jordanian custodianship on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif, and an undertaking not to undermine them. Netanyahu in particular has done as much in the past, and he can do it again. This reaffirmation to the status quo should be highlighted both publicly and behind closed doors.

- Leveraging regional normalization in support of an Israeli-Palestinian process – The opening of Al Aqsa to the Arab and Muslim worlds is a noble objective, but only if it will not be manipulated in support of the entrenchment of Israeli occupation. It is imperative to explore ways of realizing this goal as part of a process of normalization process that will actively support the resumption of a dialog between Israel and the Palestinians that addresses, rather than circumvents the core grievances of both parties, including the Palestinians. Finding a satisfactory mechanism regarding pilgrimage that is acceptable to all sides will no doubt become a factor in any relaunch of a political process. It is not too soon to plan for that eventuality.