Is there a “Likeliest” Annexation Scenario?

Context

Under current circumstances, with so many variables in play, it is difficult to predict what will transpire regarding Israeli annexation of parts of the West Bank in the days and weeks to come. Yet, by analyzing these variables, we can draw various conclusions on possible scenarios.

July 1, 2020, the highly touted date upon which Prime Minister Netanyahu promised to commence the process of annexing parts of the West Bank, is now behind us. The Israeli government’s coalition agreement leaves little doubt that July 1 was intended as a potentially significant milestone, but not a binding date:

“The Prime Minister and the alternate Prime Minister will work together and in coordination to advance peace agreements with all our neighbors and to promote regional cooperation in a variety of economic areas and the issue of the Corona crisis. With regard to President Trump’s declaration, the Prime Minister and alternate Prime Minister will act together and in a coordinated manner in full agreement with the United States, including with regard to the maps in coordination with the US and international dialogue on the issue, while pursuing the security and strategic interests of the State of Israel including the need for maintaining regional stability, maintaining peace agreements and striving for future peace agreements. The Prime Minister will be able to bring the agreement to be reached with the United States on the application of sovereignty as of July 1st, 2020 for cabinet and government debate and for approval by the government and/or the Knesset. If the Prime Minister wants to present his proposal to the Knesset, he can also do so through an MK provided that the latter is from the Likud faction, so as to ensure …After the preliminary reading, the law will be passed as soon as possible and in the quickest possible way”.

While nothing happened on July 1 and obstacles to annexation piling up, we caution against dismissing the possibility that some kind of annexation will indeed occur. There are many compelling reasons why both Netanyahu and Trump – both highly vulnerable politically and less predictable than ever – will yet greenlight annexation, in the course of the coming days or months.

Even in the absence of any decision in regard to annexation and with numerous options still under consideration, the dynamics to date suggest, with a degree of plausibility but without certainty, what appears to be the most likely plan that will emerge – assuming that plan will be released at all.

- The Plausible Annexation Schemes

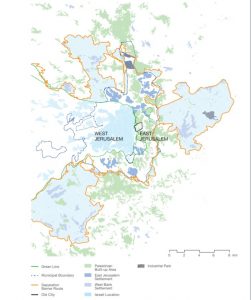

In recent weeks, there have been persistent reports in the press that the annexation scheme under serious scrutiny would “limit” annexation to the settlement blocs surrounding Jerusalem.There have been a number of versions of these reports, differing in detail, but very similar in substance. Several reports (e.g. here and here) mention Blue and White’s inclination for an annexation that would be limited to three settlement blocs, two of which, Ma’aleh Adumim and the Etziyon bloc are in “Greater Jerusalem”, the third being Ariel. Givat Ze’ev, to the northwest of Jerusalem, falls into the category of Greater Jerusalem settlement bloc, and is cited as one of the potential blocs, albeit less frequently.

E-1 Ma’aleh Adumim Bloc Givat Ze’ev Bloc

The Greater Jerusalem Settlement Blocs Etziyon Bloc

- Why do These Potential Annexation Plans Warrant Special Attention?

There are two compelling reasons that lead us to treat these prospective plans more likely than others:

- Netanyahu’s long-dated pursuit of a Greater Jerusalem umbrella municipality – On more than one occasion in the past Netanyahu has come very close to implementing schemes that are very similar or identical to the annexation of the three Greater Jerusalem blocs. The plans have gone well beyond mere concepts. Our sources have informed us that there have been protracted and in-depth deliberations in the National Security Council, which have produced a number of operational contingency plans relating specifically to these blocs.

- The Settlement Blocs Doctrine –The settlement blocs are portrayed in certain quarters as being “legitimate” settlements, on which there is an Israeli consensus. Blue and White leadership assumes that an annexation limited to the Greater Jerusalem settlement blocs will arouse less opposition, both internationally and domestically. Netanyahu’s domestic considerations are more complex, as he also fears criticism from the settlers leadership and from his own party, who will “pocket” the areas that the government has decided to annex but castigate Netanyahu for all that he left “un-annexed”. Netanyahu will no doubt be accused of betraying Judea and Samaria, while squandering the so-called opportunity created by the Trump plan.

We will now examine each of these factors in depth.

- Netanyahu’s Pursuit of a Greater Jerusalem Umbrella Municipality

The 1998 Cabinet Decision

On February 12, 1997, Netanyahu’s cabinet secretly established a “Committee for the Strengthening of Jerusalem”. One of the major objectives of the Committee was to address the “demographic threat” in Jerusalem, with its members expressing a fear that one day, East Jerusalem Palestinians could possibly comprise as much as 40% of Jerusalem’s total population (a “fear” that has subsequently materialized). The Committee recommended creating a Greater Jerusalem Umbrella Municipality, so as to incorporate all or part of the settlement blocs to the north east and south of the city, thereby enlarging the city’s Jewish population.

In June 1998, Netanyahu brought a resolution before his Cabinet proposing that the Knesset enact legislation establishing a “Greater Jerusalem Umbrella Municipality”. The West Bank settlements to be included in the Umbrella Municipality were not listed, but during the deliberations in the Cabinet, it became evident that, at the very least, these would include Givat Ze’ev to the northwest of Jerusalem, Maale Adumim to its east, and the Etziyon Bloc to the southeast. The municipalities would maintain some of their autonomy, but their powers and authorities in the fields of construction, planning, licensing etc.(that is, all that is entailed in settlement construction) would be merged with those of the Jerusalem Municipality, which would head the new body. Knowing that the international community would not countenance de jure annexation, the Cabinet elected to take steps that went beyond de facto annexation – the mingling of governmental and municipal powers in one legal framework that included municipalities on both sides of the Green Line – but fell short of the full application of Israeli law to these settlements.

After the resolution had been leaked to the United States a few days before the Cabinet session, the Clinton administration took urgent steps to prevent its approval. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright spoke personally with Netanyahu (who initially denied that any such resolution existed). So great was the concern in the Clinton administration that, in an unprecedented move, Albright convened a conference call on Shabbat with the presidents of all of the major American Jewish organizations, imploring them to help persuade Netanyahu not to pursue the scheme.

Yet, on June 28, 1998, the Cabinet approved the resolution, and instructed the clandestine commission to formulate the details and structure of the Umbrella Municipality by September 20, 1998. However, the international uproar that ensued regarding the resolution had its impact. The prospect of a UN Security Council resolution condemning Israel appeared increasingly likely, without any certainty that it would be vetoed by the US. So quietly, Netanyahu made the resolution “disappear”, and the committee never reported back to the Cabinet.

Throughout the years, there would be periodic, but cursory mention of the possibility of creating an Umbrella Municipality. However, it took 19 years before the proposal returned, and in full force. And once again, it was Netanyahu taking the lead.

The “Jerusalem and its Daughters Law”

In March 2017, four members of Knesset, including two of Netanyahu’s closest confidantes, MKs Yoav Kish and Amir Ohana, introduced legislation that was highly reminiscent of the 1998 Umbrella Municipality resolution, while going well beyond that initiative in two important ways.

Unlike the 1998 resolution, the proposed legislation entailed formal annexation of the settlement blocs around Jerusalem, citing them by name: Maale Adumim, Givat Zeev, the Etzion Bloc Municipal Council, Beitar Illit, and Efrat (the latter three comprising the Etziyon Bloc). The mechanism mirrored the two-tiered annexation of East Jerusalem in 1967: first Israeli law would be imposed on these areas, and then incorporated into the Jerusalem Municipality immediately thereafter.

Secondly, the legislation entailed excising three areas currently part of the Jerusalem Municipality: the Shuafat Refugee Camp ridge, Anata and Kafr Aqb, each of these areas home to approximately 60,000 Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem. It is important to note that these areas were not designated to be ceded to the Palestinian Authority, even though the National Security Council examined this option, which has supporters in the Government of Israel. The areas being cut out of municipal Jerusalem were to become autonomous sub-municipalities of the Jerusalem Municipality, while remaining under Israeli rule.

In October 2017, as the meeting of the Ministerial Committee for Legislation that was to approve the legislation approached, Netanyahu openly endorsed the legislation, apparently with one key reservation: the settlements under question would not, as originally planned, come under the full and direct authority of Israeli law. Once again, Netanyahu preferred the blurring of the distinction between Green Line Israel over formal annexation.

Shortly thereafter, the legislative initiative all but fell apart. The Trump administration, which had not yet despaired of receiving Palestinian support for the Trump Plan, urged Netanyahu to desist. In addition, and in a harbinger of things to come, the right-wing flank of the settler movement opposed the legislation because it was too radical: for them, the Jerusalem municipal boundary was and is sacrosanct, and redrawing the boundary in order to excise the Refugee Camp and Kafr’ Aqb would be sacrilegious. Netanyahu capitulated and withdrew the legislation.

The legislative initiative did not come to naught. In January 2018, The Basic Law: Jerusalem (legislation enacted in 1980 invoking “Jerusalem, [as the] complete and united… capital of Israel”) was amended in two significant ways:

- a transfer of any governmental authority in any part of municipal Jerusalem will require a majority of 80 of the 120 members of Knesset.

- Nonetheless, the amendment was so worded that the municipal boundaries may be redrawn so as to excise places like the Shuafat Refugee Camp and Kafr Aqb from Jerusalem (but not from Israel) with relative ease.

The domestic and international challenges to annexation

- The emerging consensus against annexation, whatever its size – By fixing July 1 as some kind of “Annexation Day”, Netanyahu created a virtually irresolvable conundrum, that invited contradictory pressures from all sides. US Ambassador Friedman set a high bar by speaking of the annexation of 30% of the West Bank. Whereas annexation of the Jordan River Valley is touted as being within a purportedly Israeli “consensus”, annexing it has encountered broad and vehement opposition internationally, most prominently but not exclusively by Jordan. An international consensus has emerged, making it abundantly clear that there is no such thing as “annexation-lite”. According to these messages, annexation, however large or small, is likely to elicit the same harsh response.

- Pressure from the settler leaderships – A significant part of the settler movement and its leadership oppose the Trump plan, even if it should include the ambitious annexation of 30% of the West Bank. In part, they assert that 30% is not nearly enough, and in part that if the price of annexation is a Palestinian state, however truncated, both annexation and the establishment of a Palestinian State must be roundly rejected.

- Lack of consensus within government – Netanyahu’s position vis a vis his coalition partners is not much better. While the fragments of the Blue-White Party are committed to support annexation, they are laying down conditions that will be unacceptable for Netanyahu. The IDF, and the security and intelligence communities have not been part of the decision-making process but warned about the violent escalation that annexation could trigger. In 1996, Netanyahu ignored the warnings of the intelligence community, and opened the Western Wall Tunnel. The opening triggered the first round of organized violence between Israel and the Palestinians since Oslo, a trauma that Netanyahu has never forgotten. It is not likely he will make moves that may spark violence without serious deliberations in the National Security Council, the Cabinet and the intelligence arms of the Israeli government.

- Opposition of Democratic party – Annexation contains the risk of creating a rift between Israel and the Democratic Party, which very well may take the White House and one or more of the houses of Congress in the November elections. The signing of a letter by 189 House democrats warning against annexation is an unprecedent show of unity against a policy pursued by the Israeli government, signed by even the most pro-Israel democrat representatives. Likewise, annexation has elicited uncharacteristically harsh criticism from important parts of the American Jewish community.

- Uncertainty regarding the White House position – Finally, it is not at all clear what the position of the United States is on the issue of annexation. Among else, there have been numerous reports on differing views of annexation on the US team itself. Is annexation a “stand alone” product, or need it be integrated into some sort of movement on the Trump Plan? How powerful and decisive is Ambassador David Friedman, universally recognized as the high priest of annexation? Is Kushner concerned that annexation will undermine his attempt to cobble together a regional coalition? Given a pandemic, mass protests and a tanking economy, is Trump willing to risk the ramifications of annexation, and the potential violence that may ensue? If so annexation in what scope? Mini? Supersized?

Consequently, annexation currently brings costs that outweigh any potential political “gain”, even from Netanyahu’s own perspective. Yet, failing to do anything on the issue of annexation will be a major blow to his already challenged credibility. Both token and large annexations may well generate consequences that are already giving Israelis second thought. Support for annexation appears to be waning, and the circumstances in which it will need to take place more daunting.

- “The Settlement Blocs” Doctrine/ or how to Legitimize Settlements “Blocs”

In the absence of any “good” alternative from Netanyahu’s perspective, Netanyahu will face three alternatives: use the surge in the contagion of Covid 19 in Israel as a pretext to abandon annexation, create circumstance leading to new elections while pinning the blame on the Blue and White Party; or find the optimal formula enabling him to pursue annexation at purportedly minimal cost (from his point of view). We will focus on the latter option.

As he seeks to reduce the cost of annexation, the most plausible scenario is that Netanyahu will prefer a substantive but minimalistic annexation that will placate his Blue-White coalition partners, be attentive to the concerns of the White House and hopefully shorten the period of time during which the Sunni states will remain “outraged” before returning to business as usual with Israel.

There is an “off-the-rack” annexation, ready for use, that purportedly fulfills those requirements: the “settlement blocs doctrine”, designed to legitimize settlement expansion in “blocs” located in the West Bank, thereby absolving the international community that for decades has been called upon to expend energy and political capital on all settlements, regardless of their location.

At the heart of this doctrine invariably includes the view, expressed by IPF’s Michael Koplow, that “pragmatism must win out over principle in this case … by creating a policy that distinguishes between kosher and non-kosher settlement growth”.

Proposing to allow construction in the settlement blocs took root during the Bush administration and the Premiership of Ariel Sharon. In his April 14, 2004 letter to Sharon, President Bush articulated a position towards legitimizing construction in settlement blocs: “…[In] light of new realities on the ground, including already existing major Israeli populations centers, it is unrealistic to expect that the outcome of final status negotiations will be a full and complete return to the armistice lines of 1949”. Sharon exploited this acquiescence in order to use the erection of the separation barrier to consolidate Israel’s hold over the settlement blocs demarked on the ground by the route of the barrier. While disingenuously protesting that the separation barrier was all about “security” and had no political ramifications, it was clear at the time, and incontrovertible today, that the route of the barrier delineates the widely accepted Israeli perception of what the settlement blocs are, and creates the means to turn these blocs into an integral part of Israel.

In later years, this attempt to deviate from international law and custom while legitimizing Israeli construction in the settlement blocs was transformed into a coherent, well-articulated doctrine. Its goal was to avoid the heavy lifting of eliciting a settlement freeze from Israel, while at the same time persuading/coercing the Palestinians into acquiescing, and proceeding with negotiations while “limited” settlement expansion proceeded apace.

Among the most prominent and earliest proponents of legitimizing settlement construction in the blocs were Dennis Ross and David Makovsky, at times former US negotiators and at others serving as policy analysts at the prestigious Washington Institute. In March 2013, with negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians stalled, Ross published a 14-point plan in the New York Times. His point number one was: “Declare that Israel will build new housing only in settlement blocs and in areas to the west of the security barrier”.

The map below delineates the settlement blocs within the route of the barrier as envisaged by Ross and Makovsky, and its impact on the West Bank. It depicts an expanded Greater Jerusalem born of the annexation of 225 sq. km. of the West Bank, with three settlement blocs seamlessly integrated into pre-1967 Israel. In a subsequent 2017 study, Ross and Makovsky clarified that “…for now, the security barrier would serve as a dividing line between where building is and is not permitted” (while there are exceptions, the term “settlement bloc” is almost universally understood as being defined by the route of the barrier).

An expanded Greater Jerusalem born of the annexation of 225 sq. km.

of the West Bank with three settlement blocs seamlessly

integrated into pre-1967 Israel

A fragmented, discontinuous Palestinian “State”, dismembered into cantons and enclaves and with no connection to East Jerusalem

While the settlement bloc doctrine has been widely accepted inside the beltway of Washington and in Israeli public opinion, it has been largely rejected by almost all the others: the Palestinians, the EU and its member states and the Arab League remains committed to the illegality of settlements under international law. Consequently, one of the prominent slogans of the settlement bloc supporters – “everybody knows this will always be part of Israel” – is valid only if the term “everybody” excludes the Palestinians, the vast majority of the international community, international law and 53 years of UN resolutions.

However for the purposes of our discussion on annexation, it is critical to note that the settlement bloc doctrine is widely accepted among some key and highly influential policy makers, a majority of the US Jewish establishment, AIPAC Democrats and a majority of the Israeli public. For them, it is almost axiomatic that the blocs are and will remain a part of Israel, and stating otherwise is a troubling sign of disloyalty to Israel and yet another example of chronic Palestinian “rejectionism”.

- From the settlements blocs doctrine to annexation

Both Ross and Makovsky have openly voiced their opposition to unilateral annexation. But without doubting their sincerity, having for years advocated policies that allowed Israel to create realities on the ground that make annexation both inevitable and irrevocable, their opposition to annexation is not entirely convincing. In a recent op-ed, they asserted that “…we think that all unilateral annexation is a mistake and hope the prime minister refrains from doing so. At minimum, we hope he will at least recognize the difference between annexing designated bloc areas versus all the settlements, including the Jordan Valley. The former would not close the door to two states”.

This is the pattern of things to come should the settlement blocs be annexed. There will be a chorus of policy-wonks, members of Congress (and we are talking Democrats as well, and not merely Trumpian Republicans), the American Jewish community etc. saying that they opposed annexation but (wink, wink) “everybody knows” that the annexation of the “blocs” are to be part of Israel anyway, “It’s not that bad”.

Except that, as we shall see, it is indeed “that bad”.

- The Impact of Settlement Blocs Annexation

Overall Impact

The annexation of one or more of the settlement blocs will have a devastating impact on the very possibility of any future agreement between Israel and Palestine. It will fragment the built-up Palestinian areas in greater Jerusalem, condemning the Palestinians to permanent occupation in an archipelago of disjointed, disconnected villages. The annexation of East Jerusalem, Ma’aleh Adumim, the Etziyon Bloc and Givat Ze’ev alone would cumulatively seize 225 sq. km. of the land mass of the West Bank.

Case study: Maale Adumim

We will limit our detailed analysis to Ma’aleh Adumim, but similar conclusions can be drawn from the other potential annexations (the Etziyon Bloc, Givat Ze’ev and possibly Ariel).

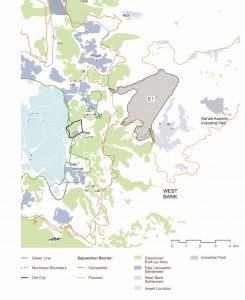

Ma’aleh Adumim is the third largest settlement in the West Bank, with approximately 38,000 residents, and its municipal boundaries encompass 50 sq. km. (for the sake of comparison, Tel Aviv’s 440,000 residents live in a city of 52 sq. km.). The planned settlement of E-1 is within the municipal boundary of Maale Adumim. The area delineated by the route of the separation barrier (most of which has not been constructed in the Ma’ale Adumim area) creates a salient approximately 60 sq. km. in size.

West Jerusalem

East Jerusalem

Ma’aleh Adumim Bloc

The Ma’aleh Adumim/E-1 Settlement Bloc

These are the ramifications of the annexation of the Ma’aleh Adumim Salient:

- The construction of E-1 would become an internal, domestic Israeli matter. Since the statutory approval process of E-1 is approaching, the approval of E-1 would become a forgone conclusion, and construction expedited.

- Ma’aleh Adumim would fragment the West Bank into two dis-contiguous cantons comprised largely of disjointed Palestinian built-up areas: there would be no real connectivity between Nablus and Ramallah in the north and Bethlehem and Hebron in the south, nor a connection between either two and Palestinian East Jerusalem.

- There would be no possibility of integrating Palestinian East Jerusalem into its natural hinterland. Cut off from the West Bank, it would make the creation of a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem virtually impossible.

- As Israel will seek to avoid annexing Palestinian population within the annexed territories, the evacuation and demolition of the Bedouin villages at Khan al Ahmar would become highly likely.

- The delineation of the bloc will, for all intents and purposes, “rid” this part of Area C of its Palestinian population:

- It will create a multi-lane road grid accessible to Israelis only, with Palestinians consigned to sealed roads used only by them.

- Palestinians owning land within the salient would lose access to their property, and it would only be a matter of time until the legal mechanism would be created that would allow for an Israeli takeover of these lands.

- Netanyahu’s dilemma: the considerations that will affect his decision

While there remains great uncertainty in regard to the type of annexation that Netanyahu may choose to pursue or not, three considerations are likely to weigh heavily on his decision:

- The White House’s insistence on a broader initiative – The Trump administration is making efforts to prove that their current policies are part of a broader effort to revive some semblance of a bi-lateral process which would benefit the Palestinian as well. However, the prospect of securing Palestinian buy-in on the basis of the Trump Plan and with the sword of annexation hanging over their heads are remote, to say the least. Should annexation proceed, we may well witness US’ pressure to grant unilateral territorial and economic concessions to the Palestinians, including, as absurd as this might sound, a unilateral land swap between different parts of the West Bank. One cannot even rule out the excision of the Shuafat Refugee Camp and Kafr Aqb from the Jerusalem Municipality – a move not only supported by Netanyahu but also appear as specific provision of the Trump Plan – that will be portrayed as just such a unilateral “concession” to the Palestinians.

- Settlers pressure – Limiting annexation to the settlement blocs will create major problems for Netanyahu with his settler base. For them, the annexation of Greater Jerusalem is no different than Olmert’s map in anticipation of the creation of a Palestinian state in those areas to the East of the barrier. Consequently, one should anticipate that there will be at least a “small”, additional annexation of one of the flagship settlements, like Ofra and Beit El.

- The paradoxical effect of the international opposition – Ironically, as Netanyahu get convinced that the international community will not distinguish between a small or large annexation, it might make sense for him to “think big”.

- The To-Do List

There has already been an impressive crescendo of opposition to annexation which has clearly had a major impact on the state of play regarding annexation. However, this achievement is hardly decisive, and how things play out in the coming weeks will likely be of critical importance. It’s worth examining what can be possibly achieved during this period.

- E-1 – E-1 and annexation are intimately interrelated. There has been a clear progression unfolding that started with creeping de facto annexation of large parts of Area C, continued with the translation of this pattern into a comprehensive plan endorsed by Trump, and further advanced by anticipatory annexation steps with Netanyahu’s recent approval of construction of the two most problematic settlement schemes, Givat Hamatos and E-1. De facto and de jure annexation of these two settlements would be the culmination of this process: an irreversible Israeli hegemony over the West Bank.

Coherent and sustained engagement by the international community – including the joint demarches by 11 EU member states – led to a deferral of the bidding process for Givat Hamatos tenders, which should have closed on June 23.

The time for similar engagement on E-1 is now, as the final date for the submission of objections to the plan, the step before the statutory approval of E-1, is July 23. It is essential to block a plan that the international community has consistently prevented since 1996. The need for further deterrents cautioning against annexation cannot wait.

- Maintain momentum. The ad hoc coalition cautioning Israel against annexation has been so far sustained, articulate and coherent. Even as many Israelis are in denial over occupation and understandably preoccupied with Covid 19 and economic survival, the messages on annexation from places as far afield as the Vatican, Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Jordan, the Democratic Party, the American Jewish community, UAE, etc., have without any doubt had an impact on Netanyahu’s and Trump’s intentions. As we enter a decisive period regarding annexation, these efforts need to be maintained and the efforts redoubled.

- Prepare to rebuild. The political stagnation regarding Israel-Palestine that has dominated in recent years has generated an international fatigue towards the conflict and a despair about doing anything serious to address it. In many quarters, this conflict is no longer prioritized, and has been downgraded. The threat of annexation has changed that, at least temporarily. Israeli occupation of the West Bank is back on the agenda, and being addressed by key players in the international community with a clarity not witnessed for years. Whether annexation takes place or not, reconstruction of credible political options will become increasingly important to address Israel’s deepening occupation and credible ways to mitigate it, and ultimately end it.