Permit Issued for 14 Units at Ras el Amud Police Station

Special issue:

Jerusalem and the Deal of the Century:

What it is, what it isn’t, does it matter?

A PDF copy of that report can be downloaded here.

Within hours of the release of the Trump Administration’s “Peace to Prosperity” proposal (“the Proposal”), long dubbed the “Deal of the Century”, it became apparent that whatever its significance might be, the Proposal would neither lead to an agreement nor generate a credible political process between Israelis and Palestinians. There are many indications that neither of these was ever intended.

Virtually no one has accepted the proposal at face value, nor has treated it as potential terms of reference in future negotiations.

Nowhere is this more the case than in regard of the Proposal’s provisions relating to Jerusalem, which deviates so much from past precedent, longstanding US policy, international law and consensus, and common sense that one is tempted to treat it as yet another work of fiction, to be relegated, along with numerous previous proposals, to the trash bin of Israel-Palestine peacemaking.

However, even if the Proposal is a “dead letter”, its provisions are worthy of careful scrutiny, and some of its key provisions have escaped notice. The Proposal is an indispensable key to understanding the most fundamental perceptions of the President and his team, as well as of Netanyahu and his constituencies in the far right. Even if never implemented, its provisions can potentially have far-reaching consequences, some of which may take place in the not-too-distant future.

We will now examine what the key provisions of the Proposal are, vis a vis Jerusalem, what they disclose and what their consequences may be.

- The Trump Proposal: Key provisions regarding Jerusalem

- The Political Status of Jerusalem

Under the provisions of the Proposal, Jerusalem will remain the undivided and exclusive capital of Israel under sole Israeli sovereignty.

The parties should not support persons or countries that deny the legitimacy of their respective capitals, or their sovereignty over them. Rejecting the legitimacy of sole Israeli sovereignty over the city will be akin to support of BDS, which is currently being criminalized.

Israeli Jerusalem will remain undivided – except when it’s not. Jerusalem will indeed be divided, albeit only partially: two Palestinian built up areas of East Jerusalem – Kafr Aqb and “the eastern part of Shuafat” – will be excised from Israel and become part of the State of Palestine.

The Palestinian capital will be in these excised areas, or in Abu Dis, and called Al Quds “or another name as determined by the state of Palestine”. Nowhere in the Proposal is the Palestinian capital called Jerusalem, a term reserved exclusively for the Israeli capital.

- The Status of the Palestinian Residents of East Jerusalem

In principle, the existing rights, entitlements of obligations of the Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem will not be affected, except for the residents of Kafr Aqb and the Shuafat Refugee Camp, who will no longer be residents of Jerusalem, nor entitled to live in or enter the city.

The “Arab residents” of East Jerusalem will have the option of a) remaining permanent residents of Israel, as is the case today, b) to become Israeli citizens, or c) become citizens of the State of Palestine. Currently, Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem are entitled to apply for Israeli citizenship, but since Israel has total discretion to deny citizenship, they are not entitled to receive it. The Proposal does not indicate if this is to change or not.

- The Religious Dimension of Jerusalem and its Holy Sites

The plurality of Jerusalem’s equities is framed in exclusively religious, not national terms. There are Jewish, Christian and Muslim dimensions to Jerusalem, while the national/political equities are exclusively Israeli or Jewish.

The proposal commends Israel for its custodianship over Jerusalem and keeping the city open and secure. This, it is proposed, should remain unchanged.

Jerusalem’s holy sites should “remain” open and accessible to peaceful worshipers and tourists of all faiths.

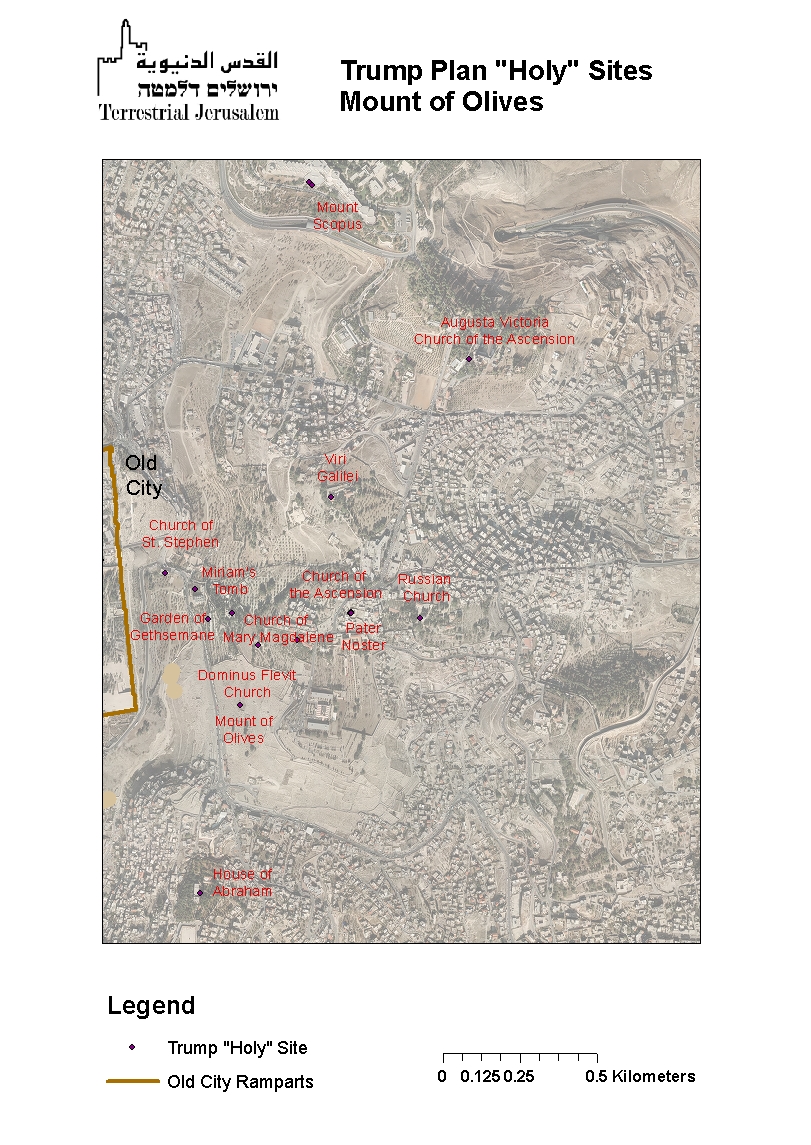

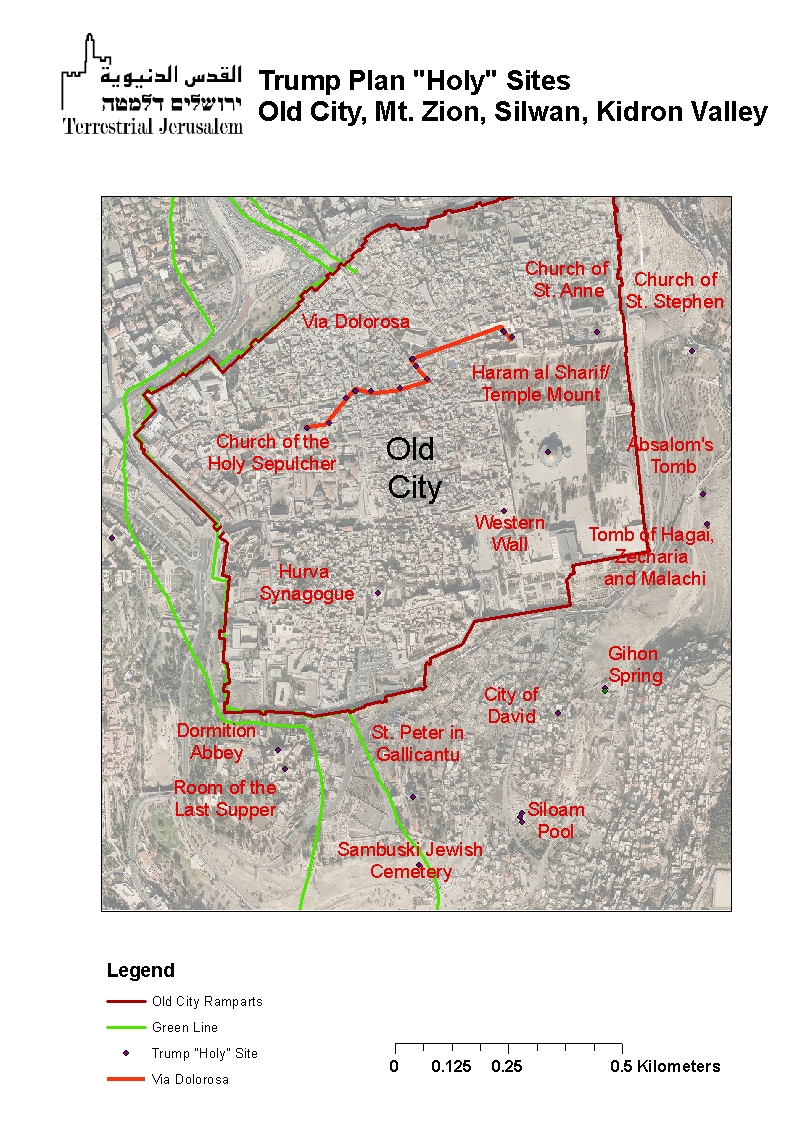

The Proposal is quite fair in the manner in which it articulates the respective theologies of Judaism, Christianity and Islam relating to Jerusalem, and does so in some depth. However, its list of Jerusalem’s holy sites lacks that parity among the three religions. The Proposal contains a list referring to 31 “holy sites” in Jerusalem.

The Proposal stipulates that “…the status quo at the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif should be continued”. However, in the following sentence, the Proposal lays out a radical departure from that status quo: “People of every faith should be permitted to pray on the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif”.

While the Proposal maintains that under Israeli sovereignty, “…all of Jerusalem’s holy sites should be subject to the same governance regimes that exist today”. There is no mention of the Jordanians, the Palestinians or the Waqf, or their roles in the management of Al Aqsa and the esplanade of the Mount. We are in no position to determine if this is an intended omission, or an oversight.

- Tourism

While the various Jerusalem components of the Proposal are skeletal in nature, seemingly disproportionate attention and details are devoted to tourism in Jerusalem.

The Proposal stipulates that Israel create a special tourist zone at Atarot, currently an industrial park several miles to the north of the city center, and which is to remain part Israel. This is to become a Special Tourist Area, even though there is nothing in the area which ends itself to tourism, nor are there sites of historic value. From this location, access to the Muslim Holy Shrines will be streamlined, with Palestinian tour guides licensed to lead tours.

It is noteworthy that the Palestinians’ permission to conduct tours is limited to the Old City, and to Christian and Muslim sites elsewhere in the city. A Joint Tourist Development Authority will be created to allow Palestine to accrue some of the economic benefits of that tourism. This is the only example in the Proposal in which the Palestinians of the West Bank have any palpable stake in Jerusalem. However, even here, Israel is the arbiter of what tourists guided by Palestinian tour guides may see, and that is limited in scope.

- What Does the Proposal Disclose About Trump’s View of Jerusalem?

- The Denationalization of the Palestinians

The Proposal declares that “[s]elf-determination is the hallmark of a nation”, and the Palestinians will fulfill that right with Palestinian statehood at some indeterminate point in the future. However, examination of the details reveals that the Palestinian rights to self-determination and statehood is radically different than those of the Jewish people. Even when created – if created – the Palestinian state will have no international boundary, nor control of entry to and exit from “Palestine”. It will be comprised of a disjointed archipelago of autonomous areas lacking any geographical integrity or contiguity, save those created by tunnels and sealed roads. It will have no airspace, territorial waters, nor electromagnetic spectrum, all of which, to the West of the Jordan River, will be exclusively vested in Israel.

The fundamental concept revealed by all this is clear: Israelis have rights, Palestinians have needs. Rights are inalienable, and to be fulfilled here and now: needs are to be addressed, often by magnanimous third parties as a reward for good behavior, and in due time. Palestinians possess, at best, a diminished, truncated nationalism to be achieved by a state that is no state at all.

If this be the case vis a vis the Palestinian national movement and Palestinian statehood, the Proposal’s provisions regarding Jerusalem go well beyond that, and are tantamount to the denationalization of the Palestinians of East Jerusalem. This should come as no surprise for those who have monitored the pronouncements of those who drafted the document. Former Envoy Jason Greenblatt has asserted that Israelis have rights in Jerusalem, while Palestinians have aspirations but, emphasizing that “…an aspiration is not a right.” It is now abundantly clear that those Palestinian aspirations will never be fulfilled in Jerusalem, unless those rights be denationalized.

The residents of East Jerusalem have individual rights as Arabs, not as Palestinians. They have religious rights in the city as Muslims, but not as Palestinians. They have material rights as tour guides and tourists (provided they limit their tourism to the sites Israel deems to be important to them). They are never even addressed as they view themselves – Palestinians. They can be Palestinian citizens, just as a German citizen may reside in France, but there will be nothing “Palestinian” about their lives in Jerusalem. Even the hesitant and now defunct commitment to maintain Palestinian institutions in Jerusalem, which accompanied the Oslo accords, has vanished. Any and all expression of Palestinian identity have been expunged. This is reflected in the basic terminology of the Proposal. As noted, the Palestinians of East Jerusalem have three options: to remain permanent residents, to become Israeli citizens or to adopt Palestinian citizenship. In each of these categories, the Proposals guarantee that the Palestinians will have “…privileges, benefits and obligations”. The term “rights” is as conspicuous by its absence as the term “obligations” is by its presence.

By all acceptable measures, be it under international law or based on the empirical realities on the ground, East Jerusalem is occupied. However, in no way does the Proposal attempt to end occupation, for the simple reason that in their operative conceptual worlds, occupation simply does not exist. The proposal offers Palestinians of East Jerusalem a devil’s bargain: shed your national identity and your aspirations for a life within a Palestinian national collective, and you will be rewarded with certain privileges.

- Enshrining a “reality” that does not exist

The Proposal repeatedly describes a reality that is utterly detached from the situation on the ground in East Jerusalem.

- The Proposal asserts that Jerusalem “should remain undivided”, while the plan itself calls for a division of Jerusalem by leaving the separation barrier intact, and excising areas currently in the Jerusalem municipal boundary and ceding them to the “State” of Palestine. The alleged non-division of Jerusalem also ignores the fact that Jerusalem is de facto divided: Israelis and Palestinians walk different streets, reside in different neighborhoods, go to different schools, shop different shops, speak different languages etc. But the greatest divide of all does not meet the eye, and this divide is not only ignored by the Proposal, it is perpetuated. There are two national collectives in Jerusalem, Israeli and Palestinian, the former being in possession of all the political power, and the latter permanently disempowered. The Lincoln inspired description of Jerusalem – “a house divided against itself, half occupied and half free” – is alien to the drafters of this Proposal.

- The Proposal asserts that “during Israel’s stewardship, it has kept [Jerusalem] open” and that its “holy sites should remain open”, “remain” and not “become”. These assertions fly in the face of a reality so stark that it is evident to every informed visitor to the city. Jerusalem is inaccessible to all but a few residents of the West Bank, and to virtually all the residents of Gaza. It is easier for the Christian worshiper from Bethlehem to pray in the Sistine Chapel in Rome than it is in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, and for the Muslim worshiper from Ramallah to go on pilgrimage to Mecca, than to pray at the Al Aqsa Mosque.

- The statement “[the] privileges, benefits and obligations of Arab residents … who choose to keep their status as permanent residents of Israel should remain the same” likely appears to be a promise to the uninformed, but to the Palestinians of East Jerusalem, it is a threat. Maintaining the existing benefits means, among else, that the Palestinians who are more that 38% of the population will receive 10-12% of the budget, that they must get accustomed to the chronic shortfall of more than 2,000 classrooms, to accept the situation where it is virtually impossible to build legally, making them ever vulnerable to home demolitions, that at times their property and residency rights hang by a thread, etc. This is the stark reality that the Proposal promises to maintain.

- Doublespeak Trumps Reality

It is not only reality that is distorted by the Proposal, but its very vocabulary.

The drafters of the Proposal are apparently incapable of calling the residents of East Jerusalem Palestinians. Doing so would imply that there are two nationalities in Jerusalem, not one. So if they are called “Arabs”, “residents” “Muslims” the claims to a national Palestinian presence in the city vanishes. The Proposal’s invocation of the right of self-determination apparently does not extend so far as recognizing the rights of the Palestinians of East Jerusalem to define themselves, maintain their identities and to be respected by others when they do so.

The drafters of the Proposal are also incapable of calling the Shuafat Refugee Camp a refugee camp, as it is universally known. Doing so would acknowledge the existence of refugees in the city; by calling the camp “the eastern part of Shuafat” – a term that sounds bizarre to anyone familiar with the city, those refugees simply do not exist.

In the public diplomacy that accompanied the publication of the Proposal – but not in the Proposal itself – it was claimed that “East Jerusalem” is to become the capital of Palestine. However the drafters of the Proposal apparently cannot bring themselves to use the term “Jerusalem” and “Palestinians” simultaneously and in a shared context. The Palestinian capital will be “Al Quds”, or any other name that selected by the Palestinian state. The recognition of any Palestinian connection to Jerusalem is no more than in a hint.

There is a common denominator in the portrayal of the stark realities of Jerusalem and the terminology used to describe them. By a systematic use of doublespeak, Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem aren’t Palestinians, Jerusalem is undivided, refugees don’t exist, Abu Dis is (wink, wink) Jerusalem but can’t be called as such, the status quo can be maintained even as it is violated, and Jerusalem is an open city “accessible” to all, which denies access to the residents of the West Bank and Gaza.

The Jerusalem of the Trump proposal does not exist in Jerusalem, but rather in the ideology of the settler right in Israel, and of the end-of-days Evangelicals in the US, where myths trump the facts.

- The Selective Sanctity of Jerusalem

The Proposal list 31 holy sites in Jerusalem, apparently for the purposes of illustration. While appearing on this list has no practical ramifications, the selection of these holy sites from the hundreds of Jewish, Christian and Muslim holy sites is revealing indeed.

- Of the 31 sites, 17 are Christian sites, 14 are Jewish sites, and one, Haram al Sharif is the only Muslim site explicitly named, and even then is portrayed as a joint Jewish-Muslim site. In addition, the Proposal cites undefined, unspecified Muslim Holy Shrines. In the Glossary of the Proposal, it states “MUSLIM HOLY SHRINES: Shall refer to the “Muslim Holy shrines” contemplated by the Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty”. There is no definition of the Muslim Holy Shrines in the Treaty, nor any other indication of what is contemplated in this regard.

- No sanctity has been attributed in the past to Mount Scopus, nor is it treated as such today. Its current location was first identified as “Mount Scopus” in the beginning of the 20th century.

- The Gihon Spring, the Pool of Silwan, and the Second Temple Pilgrimage Road all possess varying degrees on historical or archeological significance, but are by no means “holy sites”.

- The Sambuski Cemetery, which date from 19th century, is virtually unknown, has almost no physical remnants and is not frequented by tourists or pilgrims also appears on the list, with no mention of historically significant Christian and Muslim cemeteries nearby.

- If the Hurva Synagogue, built in 1864, is a holy site, why is there no mention of any of Jerusalem’s mosques – notably not even Al Aqsa – some of which date from the 7th century?

What is the common denominator of the sites mentioned?

One is tempted to claim that this is a list created by the settler organizations of East Jerusalem, but that is only partially correct:

- There is no mention of sites associated with East Jerusalem’s other settler organizations: the Tomb of Simon the Righteous, which is associated with the settlers of Sheikh Jarrah does not appears on the list, even if it is one of the six Jerusalem sites that is officially recognized by Israel official as holy sites. Only three of the six sites that are officially recognized by Israel as holy sites appear on the Proposal’s list; Israel has not officially recognized any Christian or Muslim sites as holy, not in Jerusalem nor anywhere else in Israel.

- The Tomb of Simon the Righteous is not the only site surprisingly omitted. Conspicuous by their absence are the centuries old synagogues in the Muslim Quarter in the Old City and in Batan al Hawa/the Yemenite Quarter of Silwan . These sites are associated with the Ateret Cohanim settler organization, not the Elad settlers of Silwan.

- Basically, all but two of the Jewish sites listed are directly or indirectly controlled, operated or located in “the domain” of the Elad settler organization of Silwan/the City of David. (For more on the creeping sanctification of settler Jerusalem, see Emek Shaveh’s “Selectively Sacred: Holy Sites in Jerusalem and its Environs”).

What can be learned from the list?

- There can be little doubt that the specifics relating to holy sites were in some manner made under the sole influence of the Elad settler organization.

- This selective sanctity on display in this list is quite significant and reflects a very specific, highly developed biblically driven narrative. The following description written by the renowned historical geographer of Jerusalem, applies most directly to the site dubbed “the Second Temple Pilgrimage Road” in Silwan, which in 2019 was ceremoniously opened with great fanfare by US Envoy Jason Greenblatt and Ambassador David Friedman. However, it also applies to tombs arbitrarily attributed to the prophets, and the nature of the virtual monopoly that the settlers of East Jerusalem have over the real and purported holy sites, historical and archeological sites in Jerusalem’s Old City, and its visual basin.

“Unplanned, and costing both human life and many millions of sheqels, a vast network of tunnels were created which allow for a visit to subterranean Jerusalem, that extends from what has become known as the City of David to the northern ramparts of the Old City. This underground city weaves a fabricated narrative – a Disneyland, really – that is designed to expunge thousands of years of non-Jewish history and create a purportedly direct link between the Second Temple Period until today. In this manner sewage ditches and moldy cellars are transformed into sacred sites and fabricated historical Jewish sites, with those who traverse it not encountering the embarrassing reality that reveals an Old City and Temple Mount teeming with Palestinians, in which the “city square” [as it appears in Naomi Shemer’s iconic song, “Jerusalem of Gold”] is once again devoid of Arabs.”

Meron Benvenisti, The Dream of the White Sabra, [Hebrew] Jerusalem, 2005, p. 253 (translation by the author – D.S)

- The settlers of East Jerusalem make no bones about their objectives: they seek to establish an ancient Biblical realm in and around Jerusalem’s Old City, one in which real and purported sacred, historical and archeological sites establish the hegemony of their biblically motivated narrative. In doing so, they marginalize the equities of Muslims, and turn the Palestinian residents in the targeted areas into communities at risk. As succinctly put by former Jerusalem mayor Nir Barkat, this is all about “demonstrating who really owns this city”. The Trump administration apparently agrees.

Just as the proposed change in the status quo reveals that the Trump administration has adopted the views of the extreme Temple Mount movement, its views regarding the epicenter of the conflict of between Israelis and Palestinians – the Old City and its visual basin – are virtually indistinguishable from those of East Jerusalem’s extreme settler organization, in general, and of the Elad settlers in particular.

As with the settlers of East Jerusalem, in the Jerusalem of the Trump Proposal, even mundane or questionable Jewish history is sacred, while Arab and Muslim history does not exist.

III. Does the Proposal Matter?

- The Erosion of the Status Quo on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif

There is no universally accepted definition of the status quo on the Temple Mount, and it is open to a number of differing views. The closest one can come to a broad and widely accepted interpretation is this: the Temple Mount is a Muslim place of worship, open to the dignified and respectful visits of non-Muslims, in a manner coordinated with the Waqf and compatible with the customary decorum on the site. This interpretation is entirely in sync with Netanyahu’s formative declaration on the subject: “Israel will continue to enforce its longstanding policy: Muslims pray on the Temple Mount; non-Muslims visit the Temple Mount.” For more on the status quo, see our in-depth 2015 report).

After 1967, a movement emerged, largely but not exclusively led by the extreme nationalistic religious Jewish right, which seeks to radically alter this status quo on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif. Some of the activists call for Jewish prayer on the Mount. Others seek to build a synagogue alongside of the mosques, with yet others calling for the construction of the Third Temple. A movement that was in 1967 perceived as an eccentric fringe, has since gone mainstream, and today enjoys the support of a majority of Netanyahu’s cabinet. Some cabinet Ministers have gone so far as advocating the construction of the Third Temple.

In recent years, and under pressure from the Temple Mount movement, the established status quo is being significantly eroded. Unlike the practice in past decades, on Jewish holidays, large numbers of Jewish visitors, many of whom openly and vocally advocate changing the status quo on the Mount, are allowed to visit the site, even when these visits fall on Muslim holidays (see our two last reports on these practices here and here). The police, once the most important stabilizing presence on the Mount, no longer hide their support and sympathy for all but the most extreme activists, and their hostility towards the Waqf and Muslim worshipers. The police are becoming increasingly permissive in regard to Jewish prayer other nationalistic gestures on the Mount.

Until recently, the Palestinians of East Jerusalem have viewed Haram al Sharif and the Al Aqsa Mosque as perhaps the one “safe place” where the Israeli occupation was least intrusive, and their dignity most assured. The recent events and new policies on the Mount are now eroding the “safe space” that has been maintained in large part by the status quo. They is a palpable sense of violation, desecration and danger among Muslim worshipers, and these fears are not baseless.

The cumulative message of the new policies and recent events is clear: if, in the past, the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif was a Muslim place of worship open to the visits of non-Muslim guests, it is rapidly becoming a shared Muslim-Jewish site, like the Ibrahamiya Mosque/Tomb of the Patriarchs in Hebron. This is the declared goal of the Temple Mount Movement and the deepest fears of the Muslim worshipers. And it’s already happening.

Playing into the hands of Muslim extremists, these trends have significantly exacerbated the cyclical tensions on the Mount. Given the current dynamics, an eruption of convulsive violence, which has potential of sending tremors throughout the region and beyond, is becoming increasingly likely.

As noted, the Proposal explicitly supports allowing Jewish prayer on Haram al Sharif/the Temple Mount. In doing so, the Trump administrations has adopted policies that have been rejected by every Israeli government since 1967.

This radical change in the status quo is so problematic, that since the release of the Proposal, the Trump team has begun to walk it back. In a telephonic press briefing conducted by the US team days after the publication of the Proposal on January 28, Ambassador Friedman offered the following response to a press inquiry:

“The status quo, in the manner that it is observed today, will continue absent an agreement to the contrary. So there’s nothing in the – there’s nothing in the plan that would impose any alteration of the status quo that’s not subject to agreement of all the parties. So don’t expect to see anything different in the near future, or maybe in the future at all.”

Even if taken at face value, there are three problems with Friedman’s clarification:

- Firstly, Friedman’s statement contradicts the literal meaning of the text (“People of every faith should be permitted to pray on the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif”). If Friedman’s clarification is to be taken seriously, no response to a question in a press briefing can serve as an alternative to a formal amendment to the Proposal’s text, or at the very least, an official announcement by the State Department revising the wording.

- Secondly, the explicit change in the status quo appearing in the text of the Proposal is the equivalent of “shouting it from the rooftops”. Friedman’s statement was made almost by stealth, as though the drafters of this text do not want their clarification to be noticed. In the past, Netanyahu would issue his statements regarding the status quo in a similar manner: he would issue them in English only, late on a Saturday night, and then relegating the text to some obscure location on the Prime Minister’s website.

- Finally, even if, as stated by Friedman, this change will not take place anytime soon, what has been said cannot be unsaid. The activists in the Temple Mount movement are ecstatic, flaunting their success on social media and promising to take advantage of the new situation. Instead of having a moderating influence on the various stakeholders on the Mount, this original text emboldens those who are already dangerously pushing the limits of the status quo. Anything less than an unequivocal and highly visible revision is tantamount to playing with matches at one of the most volatile locations on the planet. The prospect of an event leading to an eruption of violence is more likely today than it was before the release of the Proposal.

- Dabbling with the Demography of Jerusalem

As noted, there are two areas at the extremes of the Municipal border of Jerusalem that, while formally being part of “united Jerusalem”, have been cut off from the rest of Jerusalem by the wall. Under the provisions of the Proposal, both these locations – Kafr ‘Aqb in the north, and the ridge of Ras Hamis, the Shuafat Refugees Camp and part of the village of Anata on the east, are to become part of the Palestinian “State”.

While populations statistics relating to these areas are not entirely reliable, the best estimates are that there are 60,000 residents in each of these two areas, 120,000 out of Jerusalem’s 343,000 Palestinian residents.

There is nothing new in these proposals. Since the construction of the wall, the already modest Israeli presence in these areas has virtually collapsed. Consequently, The Israeli Government has been exploring the possibility of excising them from the city. Netanyahu went so far as preparing legislation for the specific purpose of carrying this out, only to pull back a day before the law was to be brought before the Knesset.

Just as the provision regarding Jewish prayer on the Temple Mount/Haram al Sharif is not likely to be implemented in the foreseeable future, the prospect of cutting out 120,000 residents from Municipal Jerusalem any time soon is also unlikely. But that hardly matters. This provision in the Proposal will almost certainly be one of its most consequential elements of the Proposal even if it is never carried out, and its impact likely to be felt in the not-too-distant future.

The standard of living in the Occupied West Bank is a fraction of that in Palestinian East Jerusalem. Tens of thousands of Palestinians from East Jerusalem work in Israel. Even those who are legal residents of Jerusalem and who live beyond the wall or in the West Bank nearby, have the centers of their live within the city proper (e.g. their places of work, health care, family ties, places of worship). Revoking their rights of residency will deny them access to the city, plummet them into abject poverty and have a devastating impact on virtually all facets of their lives.

The prospect of losing residency rights in Jerusalem is perhaps the most primordial fear of the Palestinian residents of the city, never far from their conscious concerns. In 2005-6, when the wall was being constructed in these areas, the Israeli Government gave periodic reassurances that the residency rights of the residents would remain intact. It made no difference. The fears of the residents were so deeply seated that tens of thousands moved to those parts of the city remaining on “the Jerusalem side” of the wall.

Today, no such reassurances are being given, and the Trump proposal makes the prospect of the next Israeli Government implementing this change in their status all the more likely. In the brief period since the release of the Proposal, the threat of losing residency rights has become one of the most prominent and heated topics of conversations in Kafr ‘Aqb and the Shuafat Refugee Camp. In the coming months, we will likely be witnessing tens of thousands of Palestinians from these outlying areas and the nearby West Bank, uprooting themselves, and moving into the unaffected areas of East Jerusalem.

Ironically, provisions that were supposed to allow Israel to “get rid of” hundreds of thousands of Palestinians in whom it has “lost interest” will likely lead to an influx into the city that will generate significant growth in the Palestinian sector of East Jerusalem. Jerusalem will become more Palestinian, not less.

- Can These Become the New Terms of Reference?

What are the prospects of the Proposal becoming the new terms in future negotiations?

There have been numerous responses of both the Arab League, the EU and their member states that share a common dialectic. On the one hand, there is a clear tendency to avoid statements that will be excessively adversarial towards Trump and the Proposal. On the other, almost all reject the plan, to the extent that it deviates from international law and a longstanding consensus regarding the creation of an independent Palestinian State based on the 1967 borders, with its capital in East Jerusalem. Some statements, like that of the EU’s High Representative, have been more forward-leaning and unequivocal than others. Some responses temper their already meek reservation with general statements that even if the Proposal is not acceptable, they called for the parties to examine it closely or that it contains positive components. Yet others, such as Orban’s Hungary, offer their unqualified support.

Even before the position of the international community has crystallized into a consistent and coherent approach, it appears likely that the subject of Jerusalem and its pivotal role in any future negotiations alone will disqualify the Proposal from becoming the new terms of reference. Under current and foreseeable circumstances, and whatever the outcome of negotiations over permanent status Jerusalem might be, the prospect that Jerusalem in general, and the Old City and Haram al Sharif/Temple Mount in particular, will be left under exclusive Israeli sovereignty appears to be remote, if not impossible. However, even though certain Arab states are willing or eager to support the plan to consolidate “a Grand Alliance” of the United States, Israel and Sunni states against Iran, Jerusalem in general, and al Aqsa in particular, will simply not let them.

To what extent does the Proposal affect the prospects of the two-state solution?

Even though the Proposal does contribute to the further loss of credibility of the existing consensus on the already challenged two-state paradigm, the possibility of the “Trump parameters” replacing that paradigm is highly unlikely. That said, even if the plan is ultimately rejected by the international community, it will likely become the “new normal” for the ideological right throughout the world, and even for elements of the Democratic Party in the United States.

- Domestic Israeli and Palestinian political ramifications

The impact of these proposals in Israel and in occupied West Bank has been far more consequential.

Netanyahu, fighting for his political life in the third round of elections in a year, has succeeded in spinning the plan as one of the most important achievements in Israel’s existence, enjoying almost wall-to-wall support within Israel. He has enthusiastically embraced the plan knowing full well that the Palestinians have no choice to reject it. With the center-right Blue and White Party embracing the initiative, the Proposal has already “moved” the dial in Israeli public opinion. The settlers and the Israeli right celebrated the Proposal’s “achievements”, such as annexation, while rejecting other key components, such as Palestinian “statehood” (however truncated that might be) or territorial concessions. Most importantly, it has unleashed their pent-up urges of annexation, making the possibility of annexation of parts of the West Bank a clear and present danger as never before. The Proposal has dealt yet another blow to the remaining forces of moderation in Israel, contributing to their largely self-inflicted decimation.

In the Occupied West Bank, the Proposal has further undermined the already tattered credibility and legitimacy of President Abbas and the Palestinian Authority, particularly in regard to security cooperation with Israel. The possibility of an eruption of violence has yet to pass.

All in all, a plan that will likely never be implemented, or even taken seriously, will almost certainly have far-reaching ramifications.

Perhaps all along, the true goal of the plan was not to generate negotiations towards an agreement. Its real objective is to make the unthinkable thinkable, and the thinkable irreversible. It is not at all clear that this attempt will fail.

- Does it “Give Us Something to Work With”?

With all its flaws and liabilities, can the Proposal or components of the plan serve as the basis of renewed negotiations or allow forward movement on Israel-Palestine, even in the absence of negotiations?

No, they can’t.

At the very foundations of the Proposal lies a very clear, consistent and coherent view of Israelis and Palestinians that not only informs, but virtually dictates all of its provisions, and not only those applying to Jerusalem: the Jewish people have been endowed with the inalienable right of self-determination, which gives rise to the right to a fully empowered state based on territorial sovereignty. Israel and the United States will bestow upon the Palestinians their own interpretation of self-determination, whereby the Palestinians are to be conditionally granted some of the trappings and trinkets of self-rule, benefits rather than rights, and even those under the tight control of Israel.

Any “plan” based on the diminished humanity of the Palestinians cannot be repaired, it cannot be salvaged, and cannot be disaggregated into its component parts.

It can only be rejected.