On January 9, Israeli authorities opened a stretch of road northeast of Jerusalem, more than 4.5 km in length. Officially called Route 4370, this stretch of road is better known as the “apartheid Road,” due to the 8-meter-high wall running down its center. The purpose of that wall: to relegate Palestinian traffic to the two-lane sealed highway on the east leading around Jerusalem (with no possibility for entering the city), while allowing Israeli traffic travel travel on the two lanes on the road’s west side, on which cars can travel through and into Jerusalem.

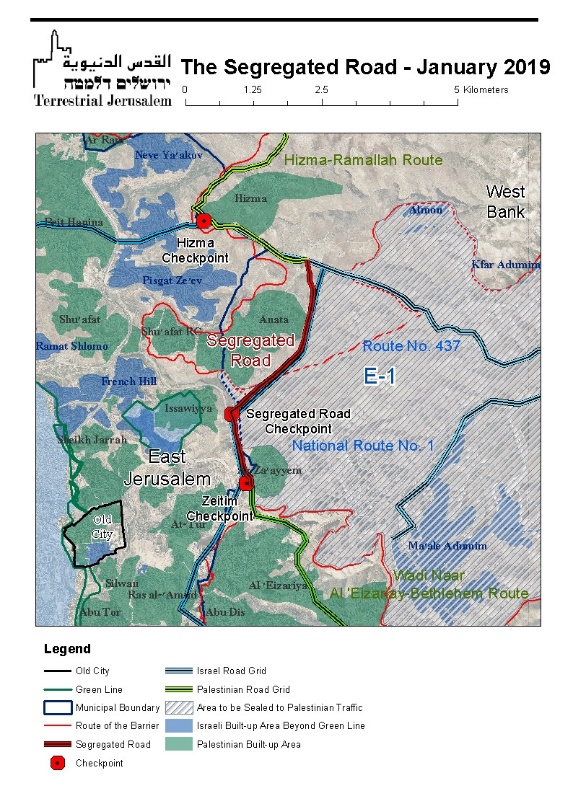

TJSpatialShapingFeb2013  Specifically, the newly opened divided highway runs between Route 437 (which links the Hizma checkpoint at the eastern entrance to Jerusalem with the settlement industrial zone known as Mishor Adumim) and the main Israeli east-west highway that runs between the coastal plain and the Jordan Valley, known as National Route 1 (not to be confused with the main north-south thoroughfare through Jerusalem popularly known as Route 1). The new Route 437 hits National Route 1 in the segment that runs between the French Hill settlement neighborhood in East Jerusalem, through Ma’ale Adumim, and onward to Jericho (bigger/downloadable map is available here).

Specifically, the newly opened divided highway runs between Route 437 (which links the Hizma checkpoint at the eastern entrance to Jerusalem with the settlement industrial zone known as Mishor Adumim) and the main Israeli east-west highway that runs between the coastal plain and the Jordan Valley, known as National Route 1 (not to be confused with the main north-south thoroughfare through Jerusalem popularly known as Route 1). The new Route 437 hits National Route 1 in the segment that runs between the French Hill settlement neighborhood in East Jerusalem, through Ma’ale Adumim, and onward to Jericho (bigger/downloadable map is available here).

Most public attention related to this new road has understandably focused on its visibly segregated character. While Israel has designated roads in the West Bank for the exclusive use of Israeli traffic before (e.g., Route 443, which was closed for many years to Palestinian traffic until 2010, when it reopened to Palestinians only after a ruling of the Supreme Court), this new road is unprecedented, being the first and only road specifically engineered to physically segregate Israeli and Palestinian traffic. Moreover, this road is not engineered merely to divide traffic along ethic/national lines; it is designed with the explicit purpose of facilitating and expanding the Israeli connection between Jerusalem and the West Bank, while further cutting off and excluding Palestinians from the city.

As stark as the moral ramifications of the opening of a segregated road are, the geopolitical impact of this road — on the state of play in Area C, on the Palestinian population in the West Bank, on the status of Jerusalem and on possible future agreements — is equally if not more consequential. We will now focus on that geopolitical dimension.

Background

The actual construction of Route 4370 commenced in the mid-2000s. It was quietly completed, for all intents and purposes, in 2007 — with the exception of the construction of an interchange at its southern edge along Route No. 1 — and in a very specific political context related to the development of E-1 during Ariel Sharon’s premiership.

It has long been recognized that the E-1 settlement plan, which entails the construction of a massive, densely populated Israeli land bridge between Jerusalem and the settlement of Ma’ale Adumim, would have devastating implications for any future political agreement. If built, it would dismember and fragment the West Bank into a northern canton and a southern canton, with no connectivity between the two, and no possibility of integrating a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem into either of them. Consequently, the fierce and universal opposition to the E-1 scheme has led successive Israeli Prime Ministers to defer its implementation.

Nonetheless, in 2004, Prime Minister Sharon expedited the statutory planning of E-1 and began the construction of a number of the plan’s elements, apparently believing that his close ties with the Bush administration would enable him to proceed with E-1 without controversy. He was mistaken. A major battle over E-1 ensued within the Bush Administration, with then-National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice leading the camp opposing the scheme and arguing that the plan would have a devastating, perhaps fatal impact on the contiguity of any future Palestinian state.

In an effort to deflect Rice’s claims regarding E-1’s impact on the contiguity of a Palestinian state, Sharon decided to build the segregated road so as to demonstrate that Palestinian traffic could, in fact, flow unimpeded between Ramallah and Bethlehem, through the E-1 area, by using this sealed road. The road reflected one of Sharon’s fundamental strategic principles: substituting “territorial contiguity” with “transportational continuity” – that is, rebutting arguments that a future Palestinian state could not be made up of geographically divided territories by insisting that engineering solutions – like bypass roads (which were being built at a fast past during that period) — could connect Palestinian areas sufficiently to allow a state to emerge, while allowing Israel to keep settlements in the West Bank and, importantly, to build E-1.

In the end, President Bush embraced Rice’s position, and his Administration’s engagement on the issue led Sharon to suspend both the statutory planning process and most of the construction. In this context, the road – which as noted earlier was completed, except for one element, in 2007, remained closed. With the planning and construction of E-1 suspended, it was no longer urgent to open it. Its major sponsor, Sharon, had fallen into a coma, and bureaucratic disputes between the IDF and the Police regarding the responsibility for the road’s checkpoints, and among the adjacent municipal councils, thwarted the opening of the road.

Until now.

Why now? The reasons are various, from the prosaic to the political – all are discussed in detail further down in this analysis. Most importantly, the road has once again become an important component in achieving Israel’s strategic objectives in Area C, as defined by Prime Minister Netanyahu. To understand these objectives, and how the opening of this new road serves them, requires first examining the patterns of movement between the northern and southern parts of the West Bank, particularly in the vicinity of Jerusalem, as they have developed over the years, and how this new road will change them.

The Patterns of Movement between the Northern and Southern West Bank

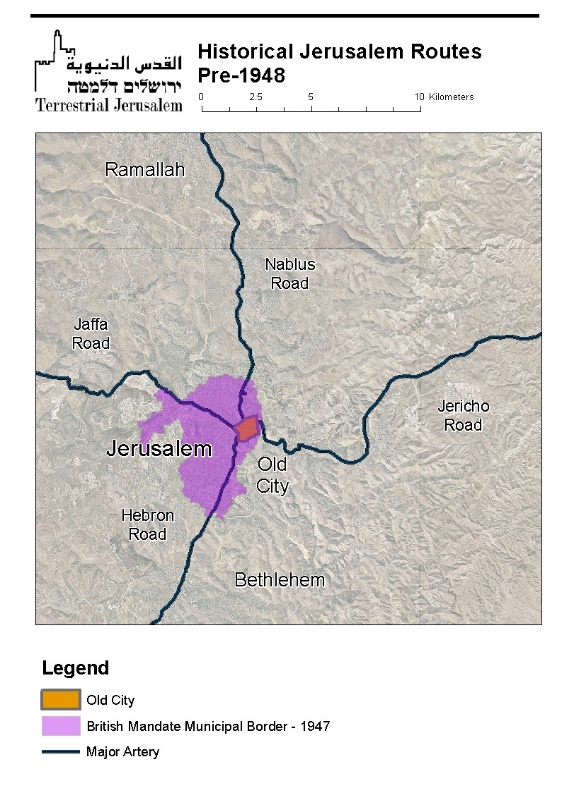

Since Biblical times, movement from the areas known today as Ramallah and Nablus in the north, and Bethlehem and Hebron to the south took place on what has been known as “the Route of the Patriarchs” – a route that led through the center of Jerusalem (bigger/downloadable map is available here).

Since Biblical times, movement from the areas known today as Ramallah and Nablus in the north, and Bethlehem and Hebron to the south took place on what has been known as “the Route of the Patriarchs” – a route that led through the center of Jerusalem (bigger/downloadable map is available here).

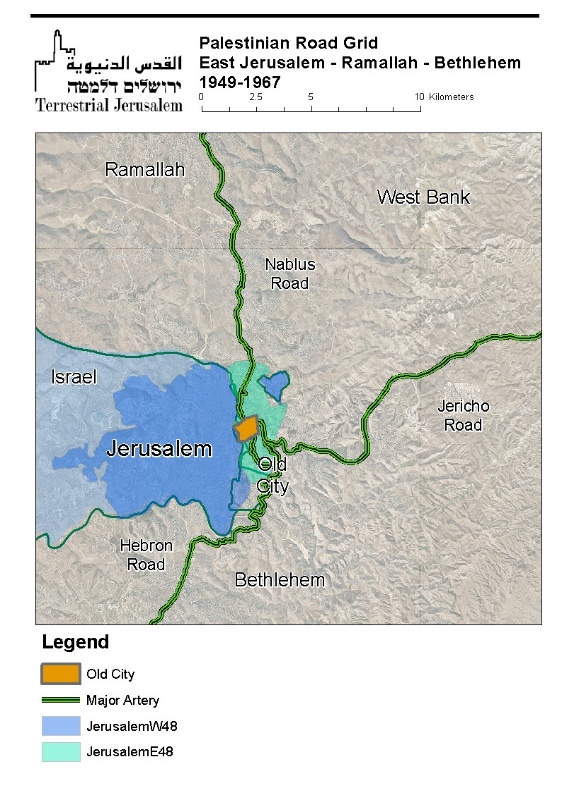

Between 1949 and 1967, with the division of Jerusalem, key segments of that route passing through Jerusalem were under Israeli control. As a result, the Jordanians created a circuitous route using secondary roads of East Jerusalem (bigger/downloadable map is available here).

Between 1949 and 1967, with the division of Jerusalem, key segments of that route passing through Jerusalem were under Israeli control. As a result, the Jordanians created a circuitous route using secondary roads of East Jerusalem (bigger/downloadable map is available here).

After 1967, with the removal of the physical barriers inside Jerusalem and between the West Bank and Jerusalem, traffic reverted to the historic route, more or less on the Route of the Patriarchs. The roads depicted in this map were used by the Palestinians of the West Bank and East Jerusalem until the1990s (bigger/downloadable map is available here).

After 1967, with the removal of the physical barriers inside Jerusalem and between the West Bank and Jerusalem, traffic reverted to the historic route, more or less on the Route of the Patriarchs. The roads depicted in this map were used by the Palestinians of the West Bank and East Jerusalem until the1990s (bigger/downloadable map is available here).

In the early 1990s, the traditional patterns of movement once again became increasingly difficult, and eventually impossible. Israel began erecting checkpoints between Jerusalem and the West Bank, and began requiring West Bank residents to obtain permits to enter the Jerusalem. In the ensuing years, with the completion of the separation barrier in the Jerusalem area, the city was effectively sealed off to Palestinian traffic from the West Bank.

In the early 1990s, the traditional patterns of movement once again became increasingly difficult, and eventually impossible. Israel began erecting checkpoints between Jerusalem and the West Bank, and began requiring West Bank residents to obtain permits to enter the Jerusalem. In the ensuing years, with the completion of the separation barrier in the Jerusalem area, the city was effectively sealed off to Palestinian traffic from the West Bank.

As a result, a new, circuitous route around the city came into being (see map below). This is the customary route used by West Bank Palestinians until today. Since the mid-1990s, any Palestinian seeking to travel from Ramallah to Bethlehem must use this circuitous route, which is twice as long as the 20 kms of the traditional route through Jerusalem, and due to both terrain and checkpoints, the trip takes many times much longer than the traditional route (bigger/downloadable map is available here).

But these routes are not only used by Palestinians. With the exception of the Wadi Nar route linking Al ‘Eizariya with Bethlehem, West Bank settlers use the same routes as Palestinians when traveling between northern West Bank settlements and Jerusalem.

The binational character of this road grid has a major impact on what settlers call their “quality of life.” Since they share the roads with Palestinians, settlers are also caught in traffic jams at checkpoints – which from their point of view is an indignity and an inconvenience that must be fixed, given that the people the checkpoints are supposed to be checking are Palestinians, not Israelis. Specifically, two key checkpoints — the Hizma checkpoint and the Zeitim checkpoint, both at entry points to Jerusalem — are a source of anger and frustration among settlers.

- The Hizma checkpoint is located on the eastern flank of the East Jerusalem settlement neighborhood of Pisgat Ze’ev. It is not only widely used by settlers entering Jerusalem from the West Bank, but by Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem. Up to 60,000 Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem reside beyond the separation barrier in places like Kafr Aqab, Semiramis and beyond. Entering Jerusalem through the Qalandia checkpoint (to the north of the city), which exclusively serves Palestinians, can entail a wait of hours. Consequently Palestinians with vehicles prefer to enter Jerusalem at Hizma. This creates a significant waiting time as well. But since this is a “bi-national” checkpoint, when the Palestinians have a long wait, so do the settlers. Long lines for Palestinians at checkpoints may be “the normal state of affairs”; for settlers it is an intolerable blow to their “quality of life.”

- A similar situation exists at the Zeitim checkpoint on national Route No. 1, which is the major artery by which the residents of Ma’ale Adumim access Jerusalem. Since the patterns of movement have turned the road into a bi-national route frequented by West Bank Palestinians, the vetting at the checkpoint is more than cursory. On a daily basis, during the morning rush-hour, there are long lines and delays not only for Palestinians but also for residents of Ma’ale Adumim seeking to traverse the checkpoint to get to their places of work in Jerusalem.

How Will the Segregated Road Change the Existing Patterns of Movement?

The segregated road will have, for now, a limited but significant impact on the patterns of movement of Israelis, and a negligible impact on the patterns of movement of the Palestinians.

However, there are a few additional steps that are likely to follow in short order, that will generate major changes in the road grids used, respectively, by Israelis and Palestinians.

Impact on Israeli patterns of movement

Immediate impact: easier access to Jerusalem for settlers. The opening of the segregated road grants the settlers from the northern part of the West Bank another point of access to Jerusalem. With this new road, they can now arrive quickly at National Route No. 1, and from there to proceed either to west into Jerusalem without additional checkpoints, or east to Ma’ale Adumim or the Jordan Valley. Settlers will thus be able to bypass the bottleneck at the Hizma checkpoint if they wish; this will alleviate congestion at that checkpoint meaning easier passage for settlers who still elect to use it. The fact that the segregated road will initially be open only between 5 AM and noon is a clear indication that the immediate motivation is alleviating the traffic jams settlers encounter during morning rush hour.

Future impact: integration into a future Eastern Ring Road. In the years to come, the segregated road will become a component of the planned “Eastern Ring Road.” That road has received statutory approval, but construction has yet to commence; it is a major project that, once started, will take many years to complete. Once completed, this new planned thoroughfare will allow Israeli traffic to proceed unimpeded from the northern half of the West Bank to the southern half without entering the center of Jerusalem. It will extend from Hizma to the north to the environs of Bethlehem in the south, with its route passing through a number of tunnels and over a number of bridges on the eastern flank of East Jerusalem. By design, it will not be accessible to West Bank Palestinians.

The following is a map of the planned Israeli road grid, as it will be after the completion of the Eastern Ring Road (bigger/downloadable map is available here):

Impact on the Palestinian patterns of movement

Immediate impact: negligible. As matters stand, the Palestinian side of the segregated road connects between Hizma and the village of Az-Zayyem. That village is technically located in Area B but is part of what Israel treats as the Maale Adumim salient, meaning that Israel has sealed the village off with a fence, leaving vehicular ingress/egress through a single route via an underpass that leads to National Route No. 1, immediately to the east of the Zeitim checkpoint. From this point Palestinians can travel east into the West Bank, but they are blocked from traveling west into Jerusalem. Now, Palestinian traffic can instead proceed from Hizma to Az-Zayyem on the segregated road, after which they can proceed to National Route No. 1 and on into the West Bank (which was already accessible to them via Route 437). This is hardly an earth-shattering development.

Future impact: measures achievable in the short-term related to the segregated road will have far reaching ramifications for Palestinian patterns of movement. Whereas the immediate impact of the opening of the segregated road is marginal, the combination of this measure with three additional steps — all of which have been widely discussed, require little or no statutory planning or construction, and are easily achievable within a short period of time — will have far-reaching ramifications for the Palestinians.

- Construction of a short segment of road that will link Az-Za’ayem and Al ‘Eizariya by means of an underpass beneath National Route No. 1. This will allow traffic to proceed from Ramallah to Bethlehem by means of the segregated road, without the use of National Route No. 1 and the segment of Route 437 between Hizma and Mishor Adumim.

- Sealing of the southern exit from Al ‘Eizariya to Palestinian traffic, thereby preventing access to National Route No. 1.

- Sealing Route 437 from westbound Palestinian traffic at Hizma, denying access into the Ma’ale Adumim salient.

The map of the Palestinian road grid will then look as follows (bigger/downloadable map is available here):

Cumulatively, these steps will effect a radical change on the Palestinians’ patterns of movement:

- The Ma’ale Adumim salient in Area C will be totally devoid of Palestinian traffic (Palestinian citizens of Israel and residents of East Jerusalem excepted). The north-south Palestinian through-traffic, and that of the area C residents of Az-Za’yyem, will be restricted to sealed roads that traverse the salient, with no possibility of leaving the road and accessing this section of Area C or entering Jerusalem.

- Currently, both Route No. 437 and National Route No. 1 as they traverse the Ma’ale Adumim salient are binational roads. After these moves, they will be “Israeli-only” roads.

- Since the roads of the Ma’ale Adumim salient will be devoid of Palestinians, it will be possible to remove the Zeitim checkpoint, allowing unimpeded traffic from Ma’ale Adumim to Jerusalem – yet another erasure of the Green Line.

- The manifestations reminiscent of apartheid – different infrastructure for different nationalities, designed both to separate the populations and to privilege one population in terms of its movement and access into key areas – are not limited to the few kilometers of the segregated road. The road allows for separate road grids for Israeli and Palestinian traffic throughout this entire area – with the Israel roads being multi-lane highways as befits a state, and with the Palestinian traffic moving on narrow, winding secondary roads linking a discontiguous archipelago of “autonomous” Palestinian areas.

Why This, and Why Now?

There are a number of prosaic reasons why the segregated road has been opened now, most prominently the resolution of the bureaucratic squabbling among the security services and among the nearby municipal councils that previously thwarted its opening. However, this should by no means blur the fact that the segregated road is a non-routine component in achieving Netanyahu’s strategic objectives in Area C.

We have long argued that Netanyahu’s settlement related activities in the West Bank, and especially in areas around Jerusalem, go well beyond his almost axiomatic support of settlements. Rather, they are components in a coherent and systematic policy building to Netanyahu’s strategic end-game: erasing the Green Line while creating a new unilaterally-defined base-line border deep inside Area C, between an expanded “Israel” and a fragmented Palestinian entity that is deprived of many of the characteristics that are critical to any reasonable interpretation of statehood. This strategy goes hand in glove with recent legislative initiatives that cumulatively will add up to a de facto annexation of Area C. For our in-depth analysis of these strategic goals, see: ”Spatial Shaping: Delineating Israel’s New Baseline Border”.

Efforts to create this unilaterally defined border deep inside Area C are based on a four-pillared policy:

- Delineating the newly defined borders by security measures, which include not only the route of the separation barrier but Israel’s extensive control of area C, well beyond the major blocs designated by the barrier.

- Consolidating the newly defined borders by means of accelerated settlement expansion within the delineated boundaries.

- Integrating the newly defined borders into pre-1967 Israel both physically and bureaucratically. Physically by means of large-scale infrastructure which seamlessly incorporates the newly defined boundaries into what since 1948 has been recognized as sovereign Israel; bureaucratically by means of legislation incrementally applying Israeli law to Area C.

- Neutralizing the Palestinian presence within the newly defined borders of Israel, by transforming the Palestinian villages into enclosed enclaves linked by sealed roads to Areas A and B, and by relocating scattered Bedouin encampments, such as Khan al Ahmar, to areas beyond the newly designated borders.

In recent years, each of these pillars consolidating Israel’s rule over area C is being systematically implemented at an ever-increasing pace.

The opening of the segregated road is a significant implementation of two of these policies: the seamless integration of the newly defined boundaries into Israel, and the neutralization of the Palestinian presence in large parts of Area C.

The Segregated Road and the Neutralization of the Palestinian Presence

Once the Az-Za’yyem-Al ‘Eizariya underpass road is completed, and Palestinian traffic is subsequently barred from Route 437 to the east of Hizma, and from National Route No. 1 to the south of Al ‘Eizariya, the Palestinian presence throughout the entire Ma’ale Adumim salient will be “neutralized” (save the presence of the Bedouin encampments such has Khan Al Ahmar, the presence of which is also imperiled):

- Routes 437 and National Route No. 1 that traverse the Ma’ale Adumim salient (both currently binational roads) will only be accessible to Israeli traffic.

- the only access that the enclosed village of Az-Za’yyem will have to the outside world will be by means of the sealed, segregated road. Consequently, while the village may be located physically within the confines of the Ma’ale Adumim salient, it will for all practical purposes have been excised from the salient and the rest of Area C.

- the Ma’ale Adumim salient will be entirely devoid of Palestinian traffic (excepting access by Palestinian citizens of Israel and East Jerusalem Palestinians).

- the claim of Palestinian “Transportational Continuity” that was invoked by Sharon will be resurrected.

The Seamless Integration of an “Israeli” Area C into Green Line Israel

Once the Ma’ale Adumim salient is inaccessible to West Bank Palestinians, there will be major changes in the way the West Bank settlements in general, and the Ma’ale Adumim salient in particular, will be seamlessly integrated into Israel proper:

- With the removal of the Zeitim checkpoint, the commute taken by the tens of thousands of residents of Ma’ale Adumim and Jerusalem will feel to Israelis no different from, for example, the commute between Jerusalem and any city inside sovereign Israel.

- Residents of Ma’ale Adumim will “enjoy” the use of roads barred to West Bank Palestinians.

- More broadly, West Bank settlers will have yet another entrance available to Jerusalem available to them (one which is denied to West Bank Palestinians).

- Settlers will have a route that allows them to avoid the daily bottleneck at the Hizma checkpoint, and for those who keep using that checkpoint, the congestion will be significantly reduced.

- The segregated road already expedites the north-south movement of the West Bank settlers. In the future, with the construction of the Eastern Ring Road, the settlers (but not West Bank Palestinians) will have a highway seamlessly linking the northern West Bank and the southern West Bank, without the necessity of traversing the center of Jerusalem (but while enjoying infrastructure that allows them seamless access to the city, if they want it).

Two Final Thoughts

Firstly, since we have noted that the segregated road constitutes the implementation of two of Netanyahu’s strategic objectives – integration of Area C and neutralization of the Palestinian presence – it is only reasonable to ask: do these developments anticipate the implementation of another strategic element of these policies, namely, consolidation by means of settlement expansion? Especially in light of the upcoming elections, does the opening of the road portend the approval of construction in E-1?

The evidence is inconclusive, but this issue requires heightened vigilance in the weeks and months to come.

Secondly, we began our discussion by stating that we would focus on the geopolitical implications, rather than the moral implications, of Israel building and opening a segregated road. But we deem it appropriate to conclude with an observation related to the reasons why people are referring to it as the “apartheid Road.”

Occupation, in and of itself, is neither a crime nor a sin. It is, in fact, a natural consequence of armed conflict, such that there are laws of war that aspire to govern the nature of the conduct of both the occupier and the occupied, until such time as the occupation ends.

However, the distinction between occupier and occupied, something that is inevitable but defensible in an inherently temporary occupation, become legally, politically and morally reprehensible when that “temporary” occupation is perpetuated in the long-term.

A “permanent” occupation (an oxymoron in and of itself), by necessity requires increasingly repressive measures in order to maintain the semblance of routine.

In this context, we would argue that the construction and now the opening of this segregated “apartheid road” is not an isolated aberration, but rather a manifestation of much broader mechanisms of separation, and a sign of things to come.

As occupation enters its 52nd year, all signs indicate that there will inevitably be additional manifestations of Israeli policy that are increasingly and chillingly reminiscent of apartheid.